During the era of the Stalin purges, it was not enough that the offending party member be found guilty. No, he also had to confess his guilt in public, so there could be no suspicion that the party had erred. He not only had to be guilty, he had to be SEEN to be guilty. Something like this same moral assumption seems to lurk at the message level of “The Valachi Papers,” an ambitious but not inspired movie about the mob.

Joe Valachi’s papers themselves were transcribed from his appearances before congressional crime committees. They provided inside dope that excited our sneaky curiosity about the outfit. But on the other hand, there was some doubt about how much Valachi really knew; he was a chauffeur, errand boy and hit man – never a member of the high councils of organized crime. Were his stories about blood oaths the real stuff, or was he just making a good story better?

The difficulty of considering the syndicate from a worm’s-eye view is one “The Valachi Papers” never quite comes to grips with. Since everything in the movie is supposedly true and told by Valachi in flashback, we have the spectacle of a minor hood constantly rubbing elbows with the big boys. At the celebrated Appalachian convention of the top bosses, for example, chauffeur Valachi is right there in the middle of things, hanging around in case anybody needs a ride.

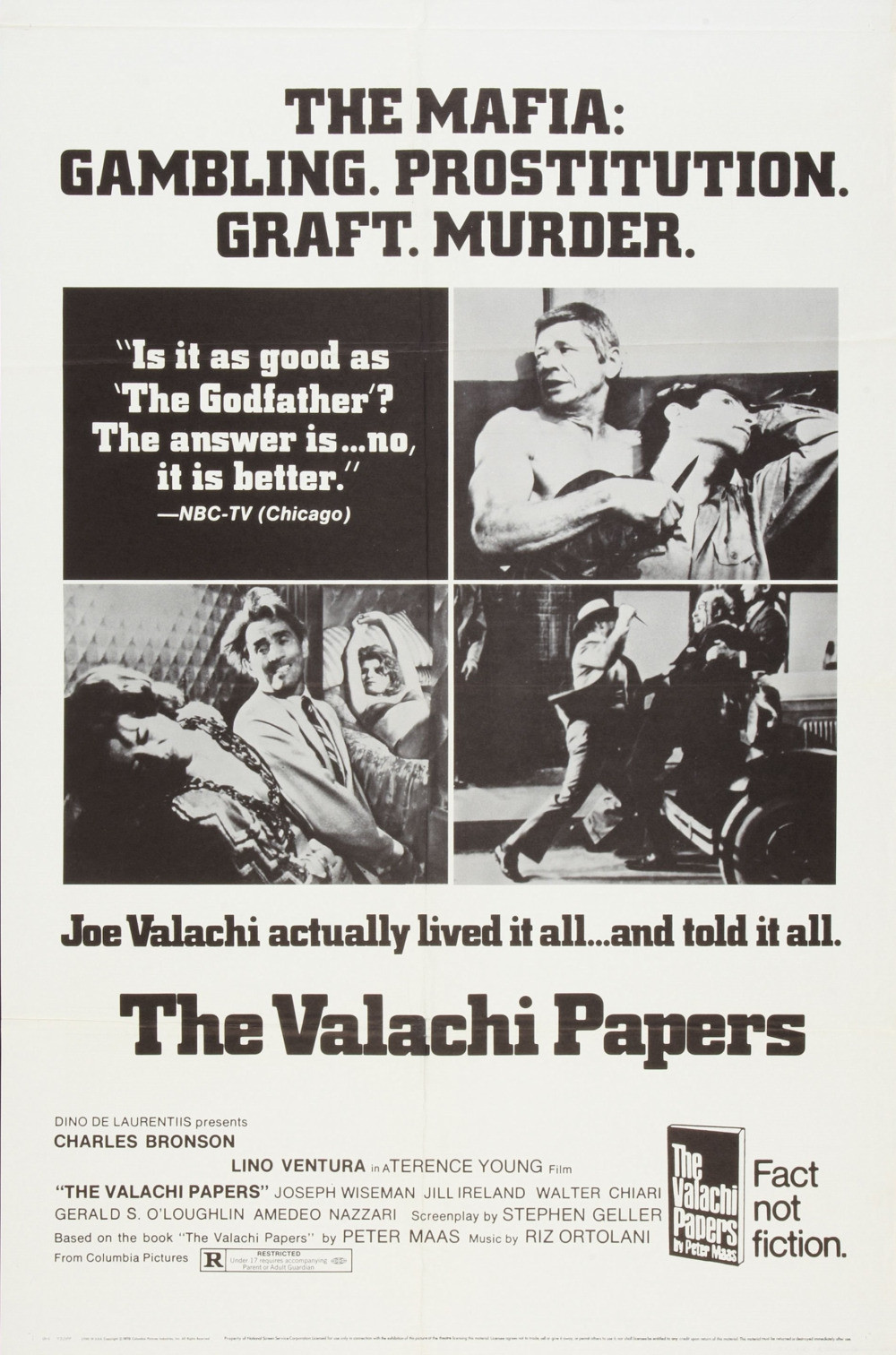

The traditional 1930s gangster movie ended with the prison doors banging shut; gangsters got to have all of the fun during the movie, but the ending had to be downbeat as they prepared to pay their debts to society. “The Valachi Papers,” as I’ve hinted, seems to be trying for some more uplifting conclusion. The movie begins with Valachi (Charles Bronson) in prison and being debriefed by a government agent. The movie is told in flashback as Valachi’s memories. The government agent doesn’t seem as concerned with punishing Valachi as with getting him to admit the error of his ways.

Valachi retains a touching faith in the Cosa Nostra; his loyalty is to it, and he seems blind to the advantages it took of him. The G-man wants to open his eyes. “They castrated your best friend and left him in agony, forcing you to kill him, and you feel no resentment?” the agent asks him at one point, and Valachi sort of shrugs his shoulders. You live by the code or you die by it.

The whole thrust of the movie is to change Valachi’s image of himself. After an unsuccessful suicide attempt, he determines to live out of “sheer spite.” If the mob has a $100,000 contract out on him, then he’s damned if he’ll kill himself and save them the money. Terence Young, who directed the movie, and Stephen Geller, who wrote it, seem to think that if they can show Valachi repenting the error of his ways, they have made a statement of some importance.

But so what? The movie’s life is in a series of fairly nice period pieces, some strong action sequences and the interesting Bronson performance. For the rest, it declines to be a traditional gangster movie and cannot approach the psychological or narrative death of “The Godfather.” So we’re not involved enough to really care that much about Joe Valachi, and the movie becomes a series of high points on the road to a labored conclusion.