Coming-of-age stories told from a girl’s perspective tend to go a couple of predictable ways: A girl expresses her sexuality and disaster ensues, leading to promiscuity, drug use, pregnancy, hooking up under the freeway, etc. Or, the story focuses on the “first love” aspect, the explosion of intense emotions (and hormones), bathed in the lens flare of nostalgia. But what about a story where a girl explores her sexuality with enthusiasm (just like a boy would), and disaster does NOT ensue? Those stories are harder to come by, although they are out there. “Diary of a Teenage Girl,” from first-time writer/director Marielle Heller (based on the novel by Phoebe Gloeckner), is one of those stories. It’s a refreshing, and, sadly, rare take on a girl coming into her own. Once Minnie (played by Bel Powley, in a major performance) discovers how great sex is, she wants more of it. Her choices are not always smart (she’s only 15), her partner is wildly inappropriate for her (not to mention illegal), but Heller has spoken about how she wanted to allow for complexity. The result is a film that is funny and sad, scary and sweet, disturbing and revelatory.

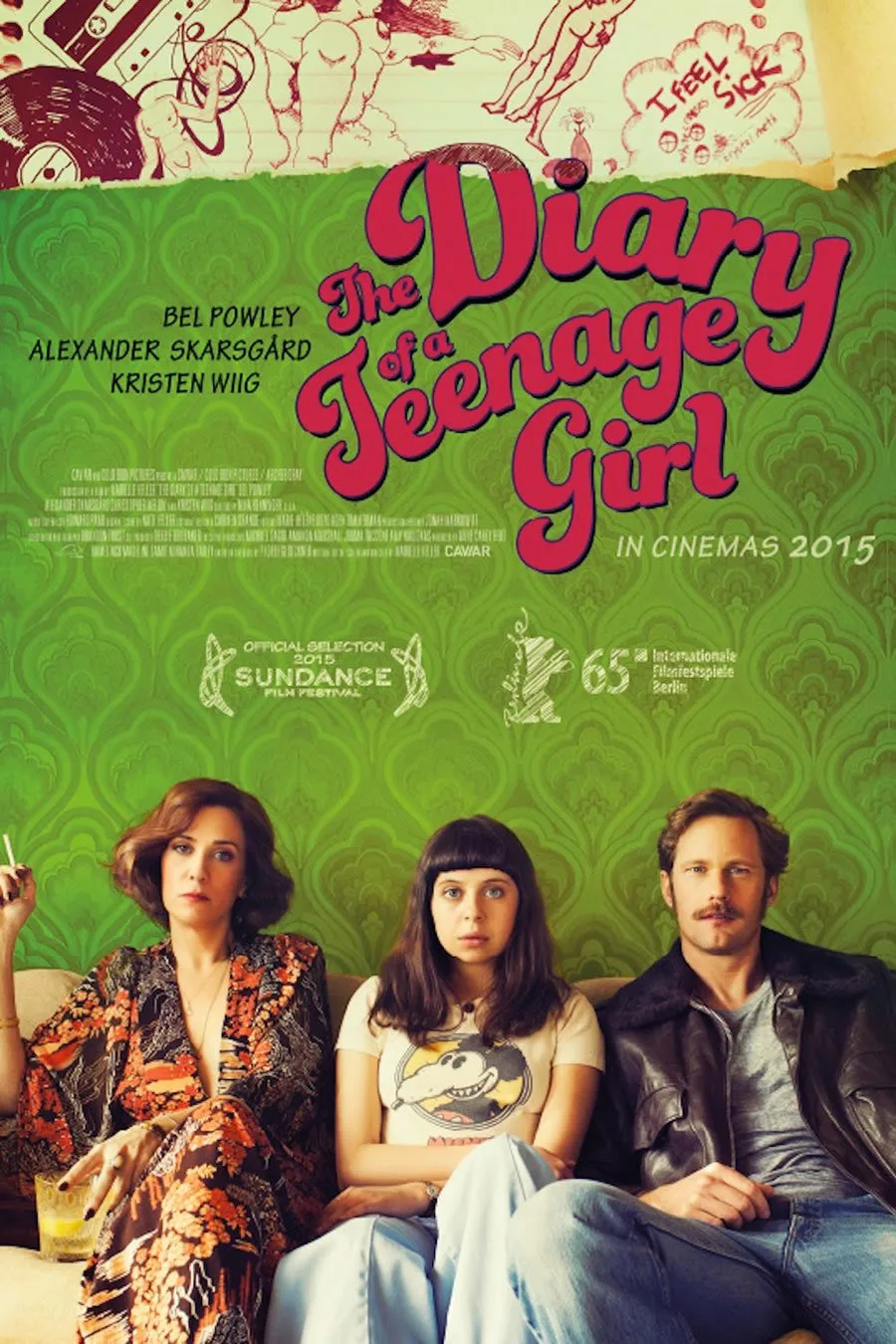

“Diary of a Teenage Girl” starts with Minnie walking through the park with a triumphant smile on her face. She says in voiceover, “I had sex today…Holy shit!” She smiles at strangers, people picnicking, throwing a Frisbee around, and the whole world seems beautiful. It’s San Francisco in the mid-1970s. The times are loose, the mood is wild. Minnie’s mother (Kristen Wiig, in yet another performance that proves she can do anything) is bitter and narcissistic, raising two daughters alone, as she parties, does drugs, and cavorts through a laissez-faire relationship with Monroe (Alexander Skarsgård). Minnie, absorbing the seething adult sexuality around her, is curious about sex, and eggs Monroe on to take her virginity. Which he promptly does, with only token resistance.

Here is where many viewers will put on the brakes. Monroe is in his 30s, involved with Minnie’s mother, and Minnie is still a minor. But as the title suggests, this is a story told from Minnie’s point of view. You could look at Minnie’s pursuit of Monroe as a way of getting back at her mother, but Heller doesn’t muddy up the waters with psychological explanations. It’s enough to Minnie that Monroe is hot, he has a cool mustache, her hormones are raging, and Monroe doesn’t turn her down when she comes on to him.

There’s a difference between portraying behavior and endorsing behavior, but often movies and filmmakers get caught up in crossfires of controversy and confusion. Did “Wolf of Wall Street” endorse misogyny or was it a portrayal of a world where misogyny ran rampant? Did “Zero Dark Thirty” endorse torture? Or was it a story told from within the community that did not question torture’s use? When 2009’s “Observe and Report” came out, a controversy ensued about one scene where Seth Rogen’s character has sex with Anna Faris, who is so wasted she is clearly unable to consent. The scene is disturbing, but it ends with a huge laugh, and therein was the problem. Did “Observe and Report” endorse date rape then? Where you come down on this issue is dependent on a lot of different factors, personal taste, political/social opinions and your feelings on what role art should play in our culture. Some feel art needs to be inspirational or educational: Films have a responsibility to show the consequences of bad behavior. Films should portray the world as it should be, not as it is. A film is dangerous if it does not point an arrow at bad behavior telegraphing “Don’t do this.” There aren’t any wrong answers, but the problem comes when the same set of criteria is used for all works of art. The purpose of the old ABC Afterschool Specials was to warn kids about the dangers that were out there. But are all films to be judged with the same set of rules? Context matters. “Diary of a Teenage Girl” is bound to stir up some controversy along these lines. Does it endorse a 35-year-old man sleeping with a 15-year-old? Shouldn’t she or he be made to “pay” for it in order to show the wrong-ness of the situation? But that opening scene, showing Minnie strolling through the sunshine, smiling to herself, loving the world, sets the mood and tells us the film’s attitude towards the story that is about to unfold.

In a less complex film, Monroe would be portrayed as a skeevy creep with no redeeming qualities. But Skarsgård, a tremendously appealing actor, destabilizes that by bringing a sweetness to Monroe, and an almost childlike dissatisfaction with his life, all of which gets focused on the eager Minnie who latches onto him like a barnacle. The relationship is, of course, hugely imbalanced, manipulative on both sides, and emotionally explosive. Monroe’s behavior is, indeed, gross. For Minnie, the revelation that someone desires her almost literally blows her mind.

Heller and cinematographer Brandon Trost create a gauzy golden-ish look, calling to mind faded photo albums, the mustard-yellows and pale-denim-blues of that era. The period is suggested, rather than fetishized. The music is atmospheric as opposed to a ready-made soundtrack, tunes coming out of jukeboxes, off record players, Minnie and her best friend jumping on the bed screaming along to The Stooges and drooling over a poster of Iggy Pop. Minnie wants to be an artist, and is obsessed with the gigantic Amazon women populating the comics of Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Minnie dreams of clumping through the streets of San Francisco, towering over the buildings, a Crumb-comic come to life. Animated images unfurl around the action throughout the film: drawings come to life, little flowers burst into blossom around Minnie’s head when she’s happy, a sketch of Monroe starts to talk to her in a heartfelt way. The animation was done by the talented Sara Gunnarsdóttir, and, similar to 2013’s “The Motel Life,” helps evoke the overheated emotions and sometimes delusional mindset of the protagonist.

“Diary of a Teenage Girl” unravels slightly in its final sequences, featuring a couple of tangents that don’t pour into the overall focus of the rest of the film. For the most part, though, “Diary of a Teenage Girl” is true to itself and its intentions. The characters are not betrayed by the plot, and vice versa.

There are other films that have looked at coming-of-age from the girl’s side of things. William Inge’s plays and screenplays in the 1950s, fraught with repressed desire and terror of being labeled a “bad girl”, were all about that. “Welcome to the Dollhouse” is in this realm, as are the films of Francois Ozon and Céline Sciamma. Nancy Savoca’s “Dogfight” places the emotional and sexual journey of Rose (Lili Taylor) on equal footing with that of Birdlace (River Phoenix), thereby avoiding the tiresome and sentimental manic-pixie-dream-girl formula. “Little Darlings,” as silly as some of it was, took the sexual urges of teenage girls seriously, adding unpredictable elements of sharp poignancy. “Little Darlings” is kind to girls who want to have sex and to say that that is not usually the case is to understate the situation. When teenage girls exploring their sexuality and enjoying it (like boys do) is seen as radical, or disturbing, or gross, then there is an urgent need for films like “Diary of a Teenage Girl.”