“Serial Mom” has as its central joke (and a very long-running joke it is) that Beverly Sutphin, a cheerful Baltimore housewife who makes terrific meatloaf, is a serial killer. The movie thinks it is funny to contrast this with the idealized homelife she provides (or thinks she provides) for her family, which seems to have been cloned from “Ozzie and Harriet” and other idealized nuclear units.

I am not sure why this isn’t very funny, but it’s not. The laughs in the movie come not from the killings or even from the mom’s secret identity, but from the details of everyday life which John Waters, the writer and director, skewers with such great affection.

There is even something about the way he shows sunlight bathing a breakfast table that’s amusing; his Sutphins look like they live in a cereal commercial. He has the look and feel of their middle-American neighborhood just right, but the movie’s comic premise doesn’t go anywhere with it.

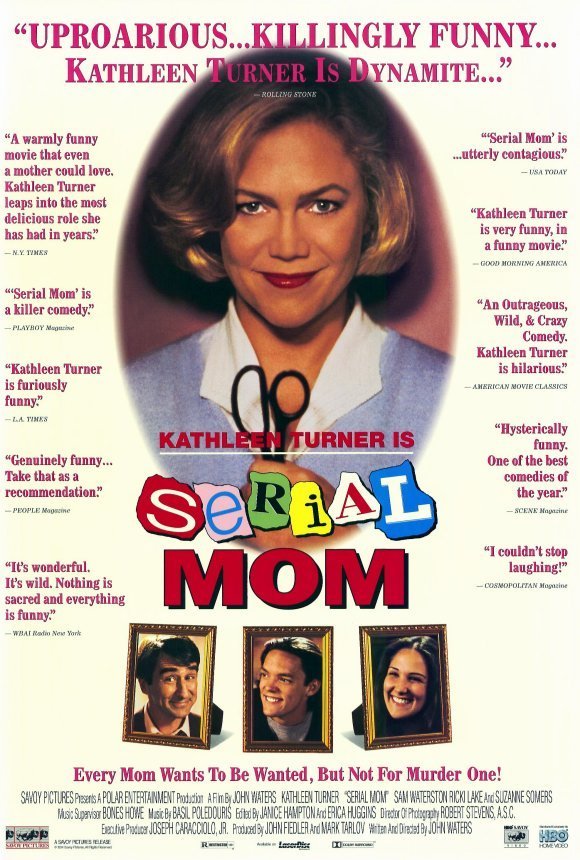

Beverly, the Serial Mom, is played by Kathleen Turner, a brave actress who has ventured here where several other actresses reportedly feared to tread. One thing I like about Turner is her willingness to tackle unlikely roles; her agent probably warned her against Danny DeVito’s “War of the Roses,” for example, but she and the equally fearless Michael Douglas took that exercise in matrimonial bloodshed and made it ghoulishly effective.

In “Serial Mom,” though, it’s not so much that Turner’s performance doesn’t succeed, as that there’s something sad about it that works against the humor. All serial killers are insane (at least I hope so). But in a comedy they need to extract some sort of zeal and manic joy from their atrocities; they have to give the audience permission, for the time being, to suspend the ordinary rules of good conduct.

In the slasher movies, the humor comes because the killers are seen as the victims of their programming, repeating the same obsessive behavior over and over again; we laugh because we see their mistake. In the classic horror films, we’re amused because the evil is so stylized we can’t take it seriously; Vincent Price licks his lips and rolls his eyes and intones his pseudo-Shakespearean imprecations, and his behavior takes the edge off his actions.

Watch “Serial Mom” closely, however, and you’ll realize that something is miscalculated at a fundamental level. Turner’s character is helpless and unwitting in a way that makes us feel almost sorry for her – and that undermines the humor. She isn’t funny crazy, she’s sick crazy. The movie shows her triggered by passing remarks (a garbage man says “somebody ought to kill” a neighbor woman who refuses to recycle). She gets a weird light in her eyes that I guess we’re supposed to laugh at, but, gee, it’s kind of pathetic the way she goes into murderous action. Like “Clifford,” this is a movie where the comedy doesn’t work because at some underlying level the material generates emotions we feel uneasy about.

John Waters has, of course, been over some of this ground before; many of his films show a surface of inane suburban normality, pierced by the secret depravities of his inhabitants. After his early X-rated weirdo extravaganzas starring Divine, he scaled back to PG-land for “Hairspray” (1988) and “Cry Baby” (1990), invocations of the early 1960s and mid-1950s. Both films, like “Serial Mom,” depend for a lot of their humor on his memories of a time when people seriously believed that cheese could come in cans.

His cast this time includes Ricki Lake (whom he discovered in “Hairspray”) as Misty Sutphin, the boy-crazy daughter who eventually begins to twig that something is wrong with mom; Sam Waterston as Beverly’s unobservant husband, and Matthew Lillard as Chip, the brother whose bad grades at school inspire his mom to run down one of his teachers with her car. And, yes, that’s Patricia Hearst in the jury box during Beverly’s eventual trial (she inspires Beverly to write an urgent note to her attorney: “Juror Number 8 is wearing white shoes after Labor Day!”) The movie has some fun with how the family deals with their mother’s serial murders (Misty sells T-shirts outside the courthouse), and of course Waters works in some movie parodies (although when Kathleen Turner spreads her legs in court in homage to Sharon Stone, it’s more awkward and uncomfortable than funny).

The more I think about this film, the more interested I am in why it doesn’t work. The crucial problem is that since we feel some sympathy for the Kathleen Turner character, we can’t laugh at her. But underneath that, somehow, is Waters’ own essential niceness.

He may have directed some of the most shocking and scatological films of our time, but at some level he always expresses a tenderness for his characters, and in “Serial Mom” he is simply not able to be cruel enough to Beverly Sutphin to make her available for our laughter.

Waters seems typecast as the author of shocking suburban melodramas, but I suspect that trapped inside of him is the soul of an entirely different kind of storyteller.