Ingmar Bergman is balancing his accounts and closing out his books. The great director is 85 years old, and announced in 1982 that “Fanny and Alexander” would be his last film. So it was, but he continued to work on the stage and for television, and then he wrote the screenplay for Liv Ullmann‘s film “Faithless” (2000). Now comes his absolutely last work, “Saraband,” powerfully, painfully honest.

Although you can see the film as it stands, it will have more resonance if you remember Bergman’s “Scenes from a Marriage” (1973). That film starred Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson as Marianne and Johan, a couple married 20 years earlier and divorced 10 years earlier, and who meet again in the middle of the night in a cabin in the middle of the woods. Their marriage has failed, their relationship has faded, and yet on this night it is more real than anything else. I wrote in 1973: “They are in middle age now, but in the night still fond and frightened lovers holding on for reassurance.”

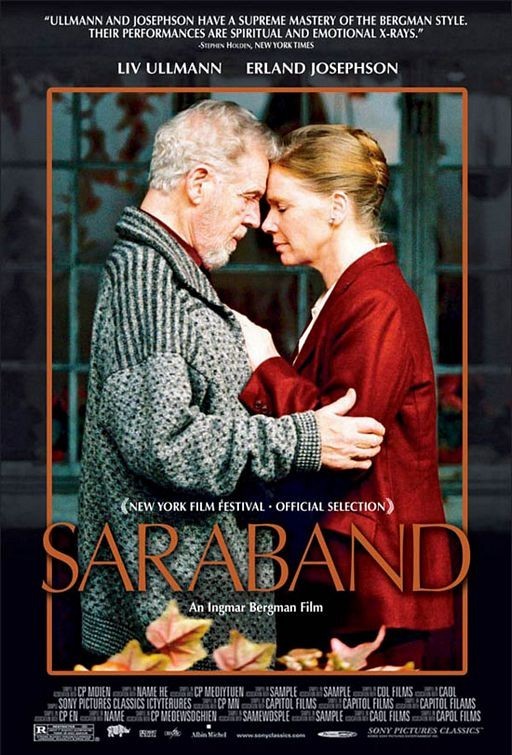

Now there is no more reassurance to be had. They must be in their 80s now; in real life, Josephson is 81 and Ullmann 65. Because Bergman’s films can be seen again and again, and because he believes the human face is the most important subject of the cinema, we are as familiar with these two faces as any we have ever seen. I saw Ullmann for the first time in Bergman’s “Persona” (1966), which I reviewed seven months after I became a film critic. Now here she is again. When I interviewed her about “Faithless” at Cannes five years ago, I noted to myself that she had not, like so many actresses, had plastic surgery. She wore her age as proof of having lived, as we all must. Now I see “Saraband” and the movie is possible because she did not allow a surgeon to give her a face yearning for its younger form.

As the film opens, she is looking through some old photographs. Marianne and Johan had two daughters together, who are now middle-aged. She never sees them; one lives in Australia, and the other has gone mad. She tells us she has not seen Johan for all of those years, but now thinks she will go to visit him. We follow her, and find that Johan is now living in misery left over from an earlier marriage. He is rich, lives in the country, owns a nearby cottage, which is occupied by his 61-year-old son Henrik (Borje Ahlstedt) and Henrik’s 19-year-old daughter Karin (Julia Dufvenius). Anna– Henrik’s wife, Karin’s mother — has been dead for two years. She is missed because she was needed, as cartilage if nothing else, to keep her husband and daughter from wearing each other down.

They are not Marianne’s problem. But she visits them, and witnesses appalling unhappiness. Johan is scornful of his son, who has value in his eyes only as the parent of Karin. Henrik is bitter that his father has money but doles it out reluctantly, to keep his son in constant need and supplication. Karin, who plays the cello, feels trapped because she wants to develop her career in the city and her father possessively hangs onto her (they sleep, Marianne discovers, in the same bed).

The movie is not about the resolution of this plot. It is about the way people persist in creating misery by placing the demands of their egos above the need for happiness — their own happiness, and that of those around them. In some sense Johan and Henrik live in these adjacent houses, in the middle of nowhere, simply so that they can hate one another. If they parted, each would lose a reason for living. Karin is the victim of their pathology.

Oh, but Bergman is sad, as he lives decade after decade on his island of Faro and writes these stories and assembles his old crew, or their children and successors, to film them. His “Faithless” showed an old filmmaker (working in Bergman’s office, living in Bergman’s house on Bergman’s island). He hires an actress to help him think through a story he wants to write. The actress, who is imaginary, is in fact playing a woman he once loved; their love caused pain to her husband, her child, and even to the director. Now in his old age he is working through it, perhaps trying to make amends. We know from Bergman’s autobiography that the story is loosely based on fact. We know, too, that Liv Ullmann, who is directing it, was also Bergman’s lover, and had his daughter.

If “Faithless” was an attempt to face persona guilt, “Saraband” is a meditation on the pathology of selfish relationships. It is filled with failed parents: All three adults lack love in their bonds with their children. It is filled with unsettled scores: Now that Henrik is 61, what does it matter that he has never become as successful as his father? The game is over. It is time to enjoy the success of his daughter — a success he will not permit, because he fears losing her. When Marianne, a witness to this triangle of resentment, returns to her own life, she returns to even less — to nothing, to photographs.

The overwhelming fact about this movie is its awareness of time. Thirty-two years have passed since “Scenes from a Marriage.” The years have passed for Bergman, for Ullmann, for Josephson, and for us. Whatever else he is telling us in “Saraband,” Bergman is telling is that life will end on the terms with which we have lived it. If we are bitter now, we will not be victorious later; we will still be bitter. Here is a movie about people who have lived so long, hell has not been able to wait for them.