Every review of “Russian Ark” begins by discussing its method. The movie consists of one unbroken shot lasting the entire length of the film, as a camera glides through the Hermitage, the repository of Russian art and history in St. Petersburg. The cinematographer Tillman Buttner, using a Steadicam and high-def digital technology, joined with some 2,000 actors in an tight-wire act in which every mark and cue had to be hit without fail; there were two broken takes before the third time was the charm.

The subject of the film, which is written, directed and (in a sense) hosted by Alexander Sokurov, is no less than three centuries of Russian history. The camera doesn’t merely take us on a guided tour of the art on the walls and in the corridors, but witnesses many visitors who came to the Hermitage over the years. Apart from anything else, this is one of the best-sustained ideas I have ever seen on the screen. Sokurov reportedly rehearsed his all-important camera move again and again with the cinematographer, the actors and the invisible sound and lighting technicians, knowing that the Hermitage would be given to him for only one precious day.

After a dark screen and the words “I open my eyes and I see nothing,” the camera’s eye opens upon the Hermitage and we meet the Marquis (Sergey Dreiden), a French nobleman who will wander through the art and the history as we follow him. The voice we heard, which belongs to the never-seen Sokurov, becomes a foil for the Marquis, who keeps up a running commentary. What we see is the grand sweep of Russian history in the years before the Revolution, and a glimpse of the grim times afterwards.

It matters little, I think, if we recognize all of the people we meet on this journey; such figures as Catherine II and Peter the Great are identified (Catherine, like many another museum visitor, is searching for the loo), but some of the real people who play themselves, like Mikhail Piotrovsky, the current director of the Hermitage, work primarily as types. We overhear whispered conversations, see state functions, listen as representatives of the Shah apologize to Nicholas I for the killing of Russian diplomats, even see little flirtations.

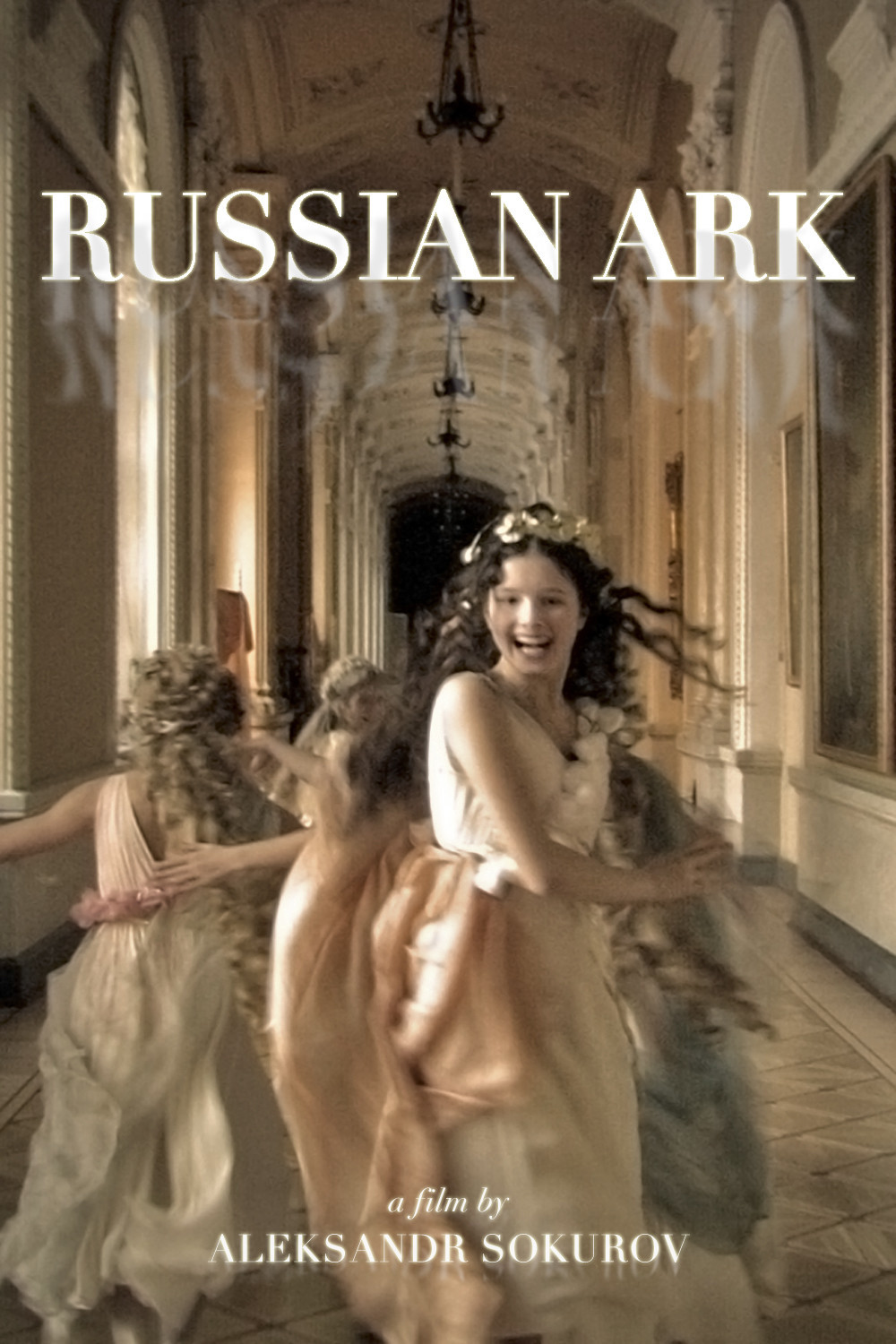

And then, in a breathtaking opening-up, the camera enters a grand hall and witnesses a formal state ball. Hundreds of dancers, elaborately costumed and bejeweled, dance to the music of a symphony orchestra, and then the camera somehow seems to float through the air to the orchestra’s stage, and moves among the musicians. An invisible ramp must have been moved into place below the camera frame, for Buttner and his Steadicam to smoothly climb.

The film is a glorious experience to witness, not least because, knowing the technique and understanding how much depends on every moment, we almost hold our breath. How tragic if an actor had blown a cue or Buttner had stumbled five minutes from the end! In a sense, the long, long single shot reminds me of a scene in “Nostalgia,” the 1982 film by Russia’s Andrei Tarkovsky, in which a man obsessively tries to cross and recross a littered and empty pool while holding a candle which he does not want to go out: The point is not the action itself, but its duration and continuity.

It will be enough for most viewers, as it was for me, to simply view “Russian Ark” as an original and beautiful idea. But Stanley Kauffmann raises an inarguable objection in his New Republic review, when he asks, “What is there intrinsically in the film that would grip us if it had been made–even excellently made–in the usual edited manner?” If it were not one unbroken take, if we were not continuously mindful of its 96 minutes–what then? “We sample a lot of scenes,” he writes, “that in themselves have no cumulation, no self-contained point … Everything we see or hear engages us only as part of a directorial tour de force.” This observation is true, and deserves an answer, and I think my reply would be that “Russian Ark,” as it stands, is enough. I found myself in a reverie of thoughts and images, and sometimes, as my mind drifted to the barbarity of Stalin and the tragic destiny of Russia, the scenes of dancing became poignant and ironic. It is not simply what Sokurov shows about Russian history, but what he does not show–doesn’t need to show, because it shadows all our thoughts of that country. Kauffmann is right that if the film had been composed in the ordinary way out of separate shots, we would question its purpose. But it is not, and the effect of the unbroken flow of images (experimented with in the past by directors like Hitchcock and Max Ophuls) is uncanny. If cinema is sometimes dreamlike, then every edit is an awakening. “Russian Ark” spins a daydream made of centuries.