There is perhaps something in the river. It floats closer on the current. It is the body of a young woman. “Poetry” opens with this extended shot, so that our realization can slowly grow. Then we meet an old woman named Mija. She learns from her doctor that she is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. It is difficult to be sure what effect this news has. She continues with her life.

Mija (Yun Jung-hee) lives in a South Korean city, where she looks after her grandson, Jongwook (Lee Da-wit), and is a care-giver for an old man who is half-paralyzed by a stroke. She is a small, unremarkable woman, cheerfully dressed, quiet, getting things done. She signs up for an adult class in poetry writing at a local community center. The teacher is not a bad teacher, maybe even a good one, although he acts as if you can be taught to write poetry. All you can do is write it. Whether it is good or not isn’t up to you.

The teacher encourages his students to look, really look, at things. He asks them if they have ever really looked at an apple. Mija goes home and really looks at an apple. It is such a perfect fruit. But then, every fruit is perfect.

Mija’s grandson is a sullen lout, a layabout with worthless friends. She is told one day that he has been implicated with five other boys in the rape of a young woman. That was the young woman in the river.

Mija carries on. She still attends class. It is very difficult to be sure what she is thinking, and this kind of film is more absorbing than those with characters who wear their emotions on their sleeve. We peer at her, we want to see into her. Yun Jung-hee’s performance is delicately given, in that she seems to be concealing nothing, and yet we remain outside. Aware of her diagnosis, we look for signs of memory loss, but she remembers, all right. It’s just that she is more focused on poetry at the moment.

There is a scene here that is heart-rending. The fathers of the other boys meet with Mija and explain they’re getting up a fund to pay off the dead girl’s mother. Mija is made to feel she must raise the money as a duty to her son. She deals with this in her own way, which I will not specify, except by saying that she begins to really look. And the poetry class, with its promise of transcendence, takes a place in her soul that we sense, rather than see.

This is the second film by Lee Chang-dong I’ve seem after “Oasis” (2002). That film also approached extreme cruelty with outward composure. It deals with a disturbed and worthless ex-con who killed a man in a hit-and-run accident. After prison, he meets the severely disabled daughter of his victim, he assaults her, and this begins a relationship that seems somehow to meet their mutual needs. Believe me, I know how horrifying that sounds. But Lee doesn’t make exploitation films, and he doesn’t find conventional answers. He is puzzled by the mysteries of inexplicable behavior.

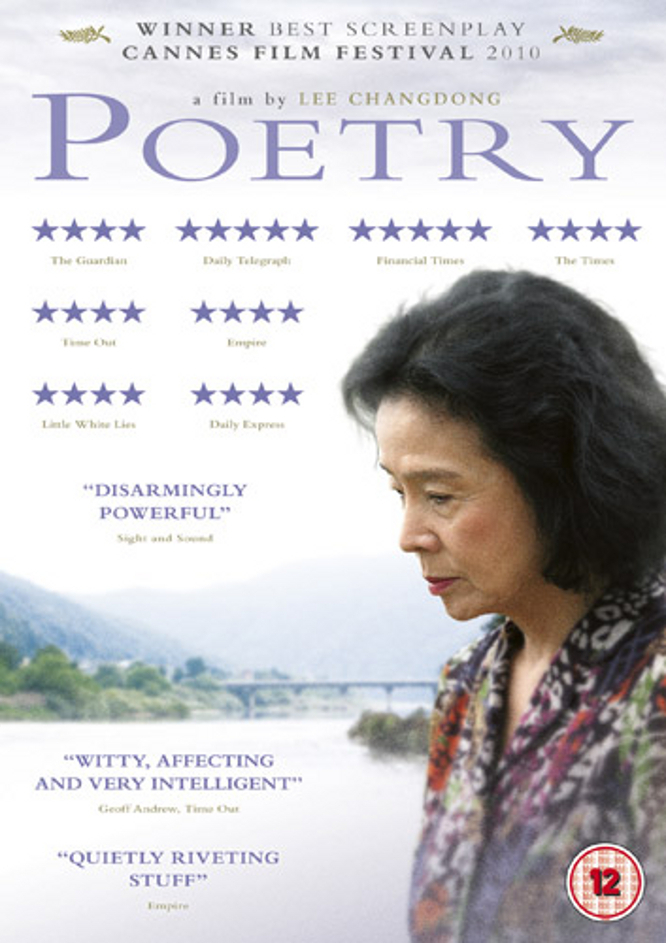

In “Poetry,” which won best screenplay honors last year at Cannes, we have a movie that is outwardly more calm. It is not seeking answers, either. It begins with events and sees how they develop. Mija, at the center, is perhaps determined to not fill her remaining memories with despair, and to avoid adding to the sum of the world’s misery. Maybe it’s as simple as that. And I must add that “Poetry” contains certainly the most poignant badminton match I can imagine.