“Outlaws & Angels” puts any disappointment felt about Quentin Tarantino’s recent, bloated Western “The Hateful Eight” into perspective. This Western too focuses on a group of morally grotesque folk spending most of their time under one roof, while encountering pain as means for revenge, as distinctly shot on film. But the difference between Tarantino and his endless imitators has always proved vast, especially when a budding filmmaker cribs his style to shallow results. A movie hopped up on the period piece sadism within Tarantino’s regurgitation cinema, “Outlaws & Angels” gravely mistakes Tarantino’s audaciousness for its own originality.

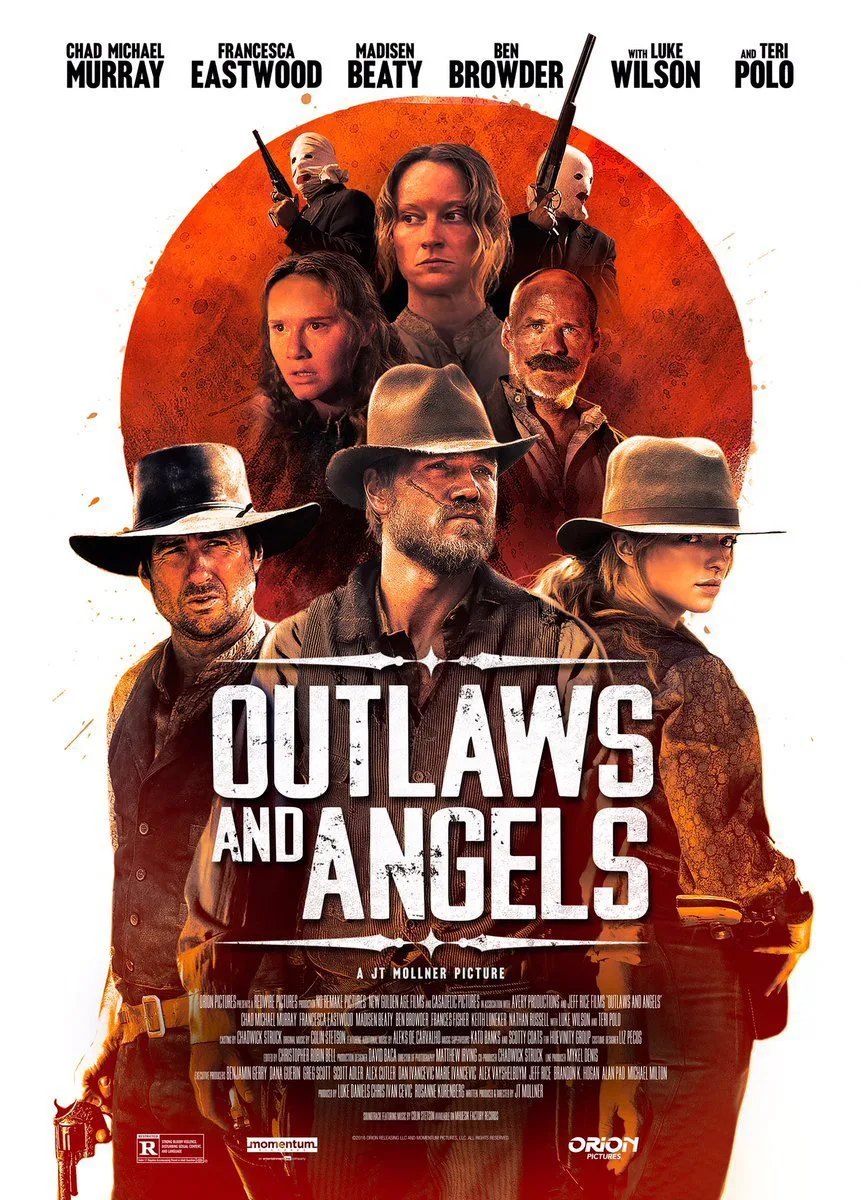

At the very least, one never questions when watching a Tarantino movie if he’s invested in his period. That’s the first huge problem with writer/director JT Mollner’s “Outlaws & Angels,” which has a nagging air of mere genre exercise from the beginning, as a group of generic bank robbers are introduced (the credits graphics pointing out their individual mugs, covered in sacks) amidst flat dialogue and even worse line delivery. Their brief interactions after a bloody heist are intercut with the man of law pursuing them (Luke Wilson), who babbles white noise voiceover while being used at most to pose in super wide shots within lifeless montages. The end point belongs to the third party, a frontier family of two daughters (Francesca Eastwood and Madisen Beaty) and a mother and father (Teri Polo and Ben Browder), who are unhinged beyond their religious fanaticism—for example, the older sister bullies the younger by sneaking up behind her and forcing her fingers down her throat, making her throw up, as kids so often do.

By the end of its first act, “Outlaws & Angels” has achieved very little. There’s no one that you to hope to get out alive, not even the debut writer/director. So it’s no thrill when the outlaws (led by Chad Michael Murray’s Henry, gurgling his dialogue like Brad Pitt’s Lt. Aldo Raine in “Inglorious Basterds”) show up to the house of the family at night, seeking food and flesh, and find themselves punishing the emasculated patriarch for previous incestual episodes with his daughters. What ensues is less horrifying than it is exceptionally desperate, as the outlaws assault members of the family, physically and sexually, with Mollner mining cheap discomfort for amoral edge. A supposed hero emerges later in youngest daughter Florence (Eastwood), although she slowly aligns with the bandits’ taste for sadism as well. With blonde hair, piercing eyes and a weapons-ready attitude, she is not the hero that takes us to a more concentrated, surprising third act, but merely gives us a fan fiction-level version of a Tarantino heroine.

The centerpiece of “Outlaws & Angels” is a scene of threatened sodomy, which runs about 10 minutes, after a character is heard defecating themselves while being dragged away. It earns the designation “centerpiece” not for a huge narrative development that happens in the scene, but because it’s clearly the moment Mollner put the most effort into; to block his actors so that they can shift in and out of the room with a camera that moves around a dinner table, all to embrace the grit that comes from not cutting away from an image captured on film. The failure of this scene is emblematic of the entire project: the stale dialogue between a threatening Murray and a terrified Browder would have been equally expressive in grunts and shrieks, this talky moment lacking the tension that can make Tarantino’s iconic, word-driven stand-offs captivating. As a single take, it only reminds the viewer of how often the movie is pointed towards showmanship—watch me splatter my actress in red corn syrup in slow motion while playing an Erik Satie piece—and that, not coincidentally, it has huge pacing issues.

For whatever other Westerns may have also inspired “Outlaws & Angels” (Frances Fisher of “Unforgiven” makes a brief cameo), Mollner’s contribution always comes back to its core Tarantino influence—even the film’s allegiance to Kodak film stock makes its blood-bursting action directly echo the albeit smaller-scale violence of “Django Unchained.” But in a sea of grimy indie Westerns, especially ones that started with the same genre canvas (last year’s “Bone Tomahawk” comes to mind, and is far more innovative), “Outlaws & Angels” is a thoroughly ugly example of when “Tarantino-esque” is the most generous compliment.