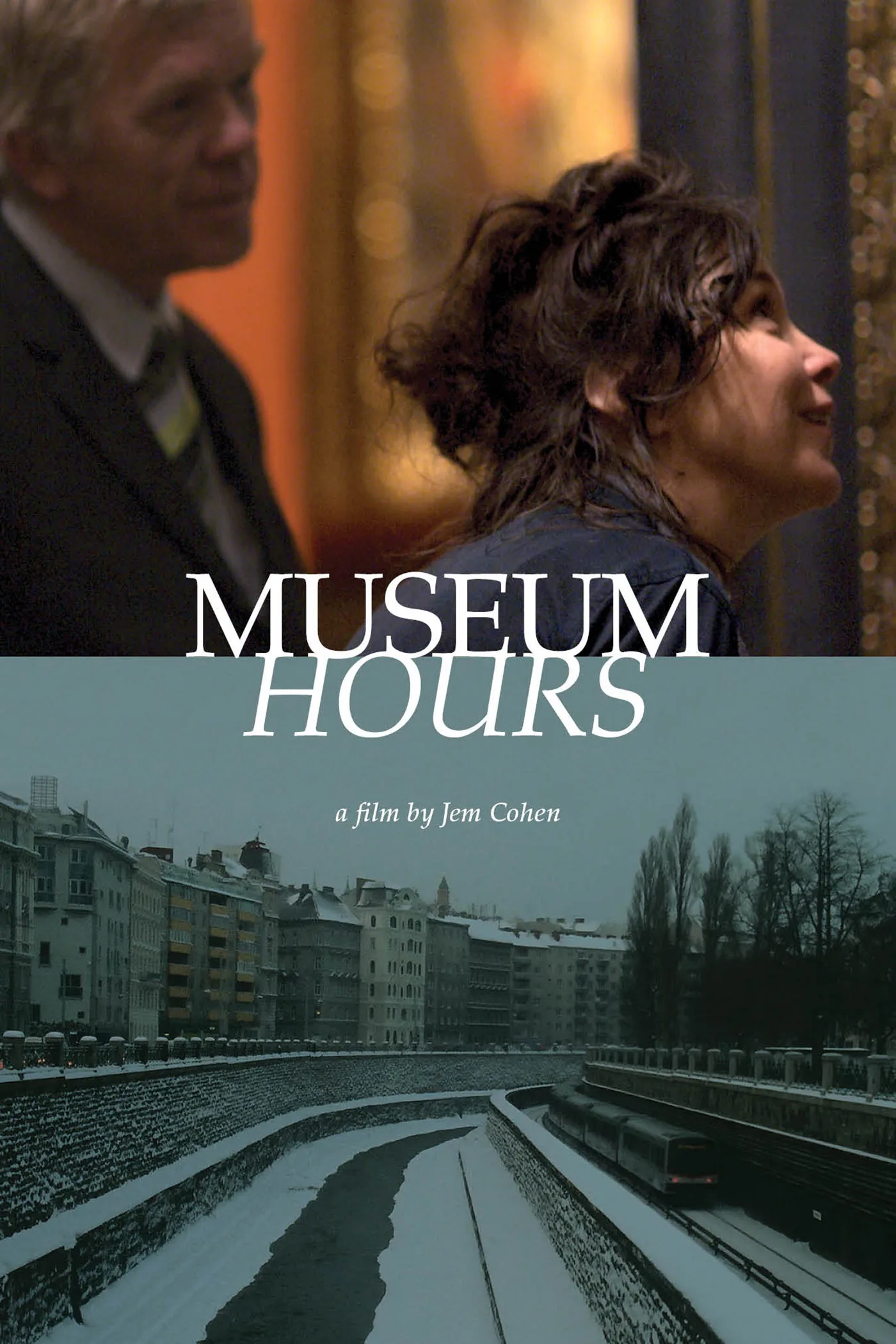

Quick, name the last great film you saw that was a true-to-life telling of how friendship works. Not a frathouse bro-mance or other Hollywood formula for fraternizing, but a film that leaves you thinking, “This is how people really get along. This is how we talk to each other and share our lives.” Now ask yourself when was the last time you saw a great film about art. How many movies about museums can you expect to see in a given year? I’m staring at a list of 100 or so first run movies that I saw in 2013 and only one film matches these criteria. Luckily that film, “Museum Hours”, fits them all brilliantly.

The film’s first shot introduces us to Johann (Robert Sommer), a security guard at the majestic Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. Seated quietly underneath masterpieces by the likes of Rembrandt and Bruegel, he seems as unremarkable as the guards we pass by whenever we visit galleries. But over the course of this film, director Jem Cohen will have us pay attention to him and many other things that we normally overlook, for they all possess incredibly rich experiences to share, if we just pay attention to them.

“What is it about some people that makes one curious?” Johan asks in voiceover. He’s speaking specifically about Anne (Mary Margaret O'Hara), a middle-aged Canadian woman who visits the museum, but is actually in Vienna to tend to a comatose cousin, largely because she was the only relative the hospital could reach. Alone in a strange city, she too is in need of help, and Johan does what he can, getting her a museum pass and accompanying her on hospital visits. Neither of them have much money, but that simply affords them time to spend talking and getting to know each other as they explore the city on the cheap. As we follow them, we get to know the city as well, not in a glamorous touristy way, but in a way that’s more modest and genuine: the subdued textures of its ancient streets, and the warm, inviting moods of its working class cafes and bars.

This story might recall another famous movie about a couple exploring Vienna, Richard Linklater’s swooningly romantic “Before Sunrise“. But unlike that youthful coupling, here there’s no chance of an amorous encounter between the leads, for reasons I’ll leave for you to discover. Here the two talk with no agenda other than to enjoy each other’s company, discussing their families, their jobs, and their honest reactions to the artworks in the museum. Johan is able to deliver exquisite descriptions of many paintings, as he’s spent countless hours looking at them. Anne’s responses are more impulsive: she sees Adam and Eve hanging naked on the wall and talks about an old boyfriend who would walk around nude “as if he was in a tuxedo.” She catches herself mid-sentence: “This is too much information!”

The film then takes a mysterious turn with a sequence of museum visitors walking as naked as some of the figures painted on the walls. Is Cohen making a direct comparison between the classic nudes and the live figures in front of his camera? Or is he evoking a state of total openness that great art can inspire? Paradoxically, museums seem to be a place that shut down such openness, dressed as they are in an aura of class and decorum. In another key scene, a museum guide (Ela Piplits) discusses Breugel’s paintings with visitors, politely entertaining their amateur interpretations before delivering an exhaustive (and exhausting) account of the historical and artistic contexts for appreciating the works. The guide’s vast array of knowledge is impressive, and yet somehow oppressive; her passion for these works is obvious, and yet it threatens to stifle those whom she is eagerly inviting to share her enthusiasm.

To his credit, Cohen’s eye is more open and loose in generating meanings both in and outside the Kunsthistoriches. To him, the streets of Vienna are as delectable a gallery of images as the museum; he even juxtaposes audio from a museum guide with scenes from a flea market. There’s a generous assortment of everyday sounds and images that manage to be sharply detailed yet elusive in meaning. Cohen, a New York-based filmmaker, has a street-bred punk sensibility, having made music films with the likes of Patti Smith and Fugazi. Like those artists, he mines poetry out of the raw, unpretentious materials of the quotidian. These happen to be the same qualities found in Breugel’s sublimely grimy panoramas of human squalor and salvation from over 500 years ago. As Cohen brings new life to the museum experience, he also brings the refined eye of the artist to look at everyday life.

Key to tying the two worlds together are Sommer and O’Hara as the leads. Neither are professional actors; O’Hara is a self-described “non-disciplinary” artist of many interests; her face shines with an inner light of charismatic goodness, while her speaking style has a charming flightiness that resembles a hummingbird. Sommer, a former road manager for rock bands who now works for the Viennale Film Festival, bears a demeanor that exudes zen-like tranquility. For Cohen to entrust his film to two unproven talents, and for it to pay off in such exquisite moments between the two of them, attests to a unique approach to casting that sees the star power of one’s simple humanity.

“Museum Hours” is a unique film that creates a richly rewarding experience from the scraps of life. It doesn’t rely on A-list actors or expensive sets; true that it films inside one of the world’s greatest museums, but it also questions what it is that we value in the museum experience. Is it to look at fancy paintings and feel cultured, or is it to experience something more direct: to dare to unsheathe oneself of one’s expectations and inhibitions, and truly embrace what a work of art can offer? And then, how could one carry that open mindset to embrace all of life itself? With patient attention and quiet devotion, these are challenges that this film dares to tackle.