John Sayles’ “Lone Star” contains so many riches, it humbles ordinary movies. And yet they aren’t thrown before us, to dazzle and impress: It is only later, thinking about the film, that we appreciate the full reach of its material. I’ve seen it twice, and after the second viewing, I began to realize how deeply, how subtly, the film has been constructed.

On the surface, it’s pure entertainment. It involves the discovery of a skeleton in the desert of a Texas town near the Mexican border. The bones belong to a sheriff from the 1950s, much hated. The current sheriff suspects the murder may have been committed by his own father. As he explores the secrets of the past, he begins to fall in love all over again with the woman he loved when they were teenagers.

Those stories — the murder and the romance — provide the film’s spine and draw us through to the end. But Sayles is up to a lot more than murders and love stories. We begin to get a feel for the people of Rio County, where whites, blacks, Chicanos and Seminoles all remember the past in different ways. We understand that the dead man, Sheriff Charlie Wade, was a sadistic monster who strutted through life, his gun on his hip, making up the law as he went along. That many people had reason to kill him — not least his deputy, Buddy Deeds (Matthew McConaughey). They exchanged death threats in a restaurant, shortly before Charlie disappeared. Buddy became the next sheriff.

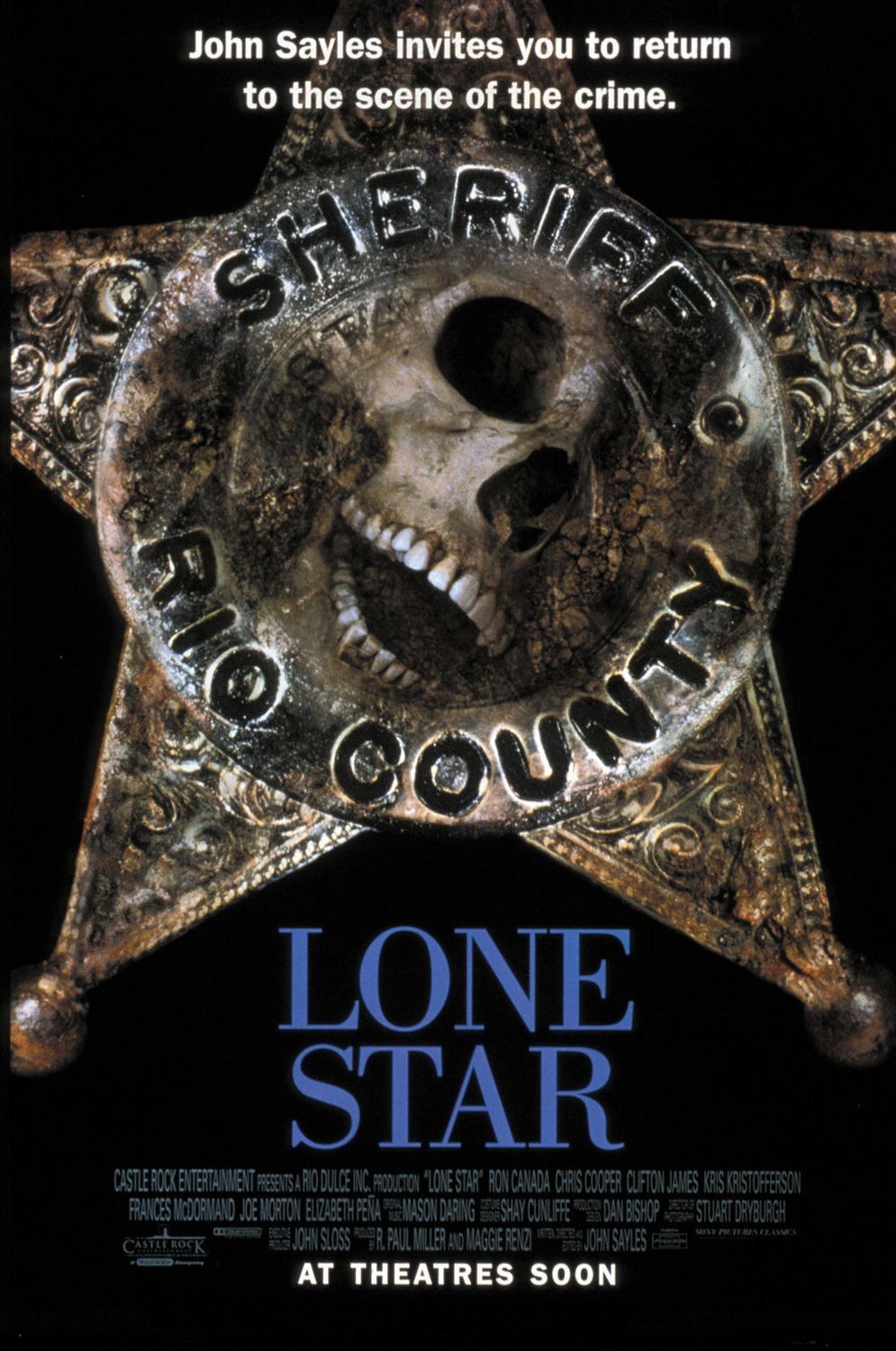

Now Charlie’s skull, badge and Masonic ring have been discovered on an old Army firing range, and Buddy’s son, Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper) is the sheriff on the case. He wanders through town, talking to his father’s old deputy (Clifton James), and to Big Otis (Ron Canada), who ran the only bar in the county where blacks were welcome, and to Mercedes Cruz (Miriam Colon), who runs the popular Mexican restaurant where the death threat took place.

Along the way, Sam does a favor. A kid has been arrested for maybe stealing car radios. He releases him to the custody of his mother, Pilar (Elizabeth Pena). He is pleased to see her again. Pilar and Sam were in love as teenagers, but their parents forced them to break up, maybe because both families opposed a Mexican-Anglo marriage. Now, tentatively, they begin to see each other again. One night in an empty restaurant, they play “Since I Left You, Baby” on the jukebox and dance, having first circled each other warily in a moment of great eroticism.

All of these events unfold so naturally and absorbingly that all we can do is simply follow along. Sayles has made other films following many threads (his “City of Hope” in 1991 traced a tangled human web through the politics of a New Jersey city). But never before has he done it in such a spellbinding way; like Faulkner, he creates a sure sense of the way the past haunts the present, and how old wounds and secrets are visited upon the survivors.

“Lone Star” is not simply about the solution to the murder and the outcome of the romance. It is about how people try to live together at this moment in America. There are scenes that at first seem to have little to do with the story’s main lines. A school board meeting, for example, at which parents argue about textbooks (and are really arguing about whose view of Texas history will prevail).

Scenes involving the African-American colonel (Joe Morton) in charge of the local Army base, whose father was Big Otis, owner of the bar.

Another scene involving a young black woman, an Army private, whose interview with her commanding officer reveals a startling insight into why people enlist in the Army. And conversations between Sheriff Deeds and old widows with long memories.

The performances are all perfectly eased together; you feel these characters have lived together for a long time and known things they have not spoken about for years. Chris Cooper, as Sam Deeds, is a tall, laconic presence that moves through the film, learning something here and something there and eventually learning something about himself. Cooper looks a little like Sayles; they project the same watchful intelligence.

As Pilar, Elizabeth Pena is a warm, rich female presence; her love for Sam is not based on anything simple like eroticism or need, but on a deep, fierce conviction that this should be her man.

Kris Kristofferson is hard-edged and mean-eyed as Charlie Wade, and there is a scene where he shoots a man and then dares his deputy to say anything about it. Wade’s evil spirit in the past is what haunts the whole film, and must be exorcised.

And then there is so much more. I will not even hint at the surprises waiting for you. They’re not Hollywood-style surprises — or yes, in a way, they are — but they’re also truths that grow out of the characters; what we learn seems not only natural, but instructive, and by the end of the film, we know something about how people have lived together in this town, and what it has cost them.

“Lone Star” is a great American movie, one of the few to seriously try to regard with open eyes the way we live now. Set in a town that until very recently was rigidly segregated, it shows how Chicanos, blacks, whites and Indians shared a common history, and how they knew one another and dealt with one another in ways that were off the official map. This film is a wonder — the best work yet by one of our most original and independent filmmakers — and after it is over, and you begin to think about it, its meanings begin to flower.