Some people become clowns; others have clownhood thrust upon them. It is impossible to regard Roberto Benigni without imagining him as a boy in school, already a cutup, using humor to deflect criticism and confuse his enemies. He looks goofy and knows how he looks. I saw him once in a line at airport customs, subtly turning a roomful of tired and impatient travelers into an audience for a subtle pantomime in which he was the weariest and most put-upon. We had to smile.

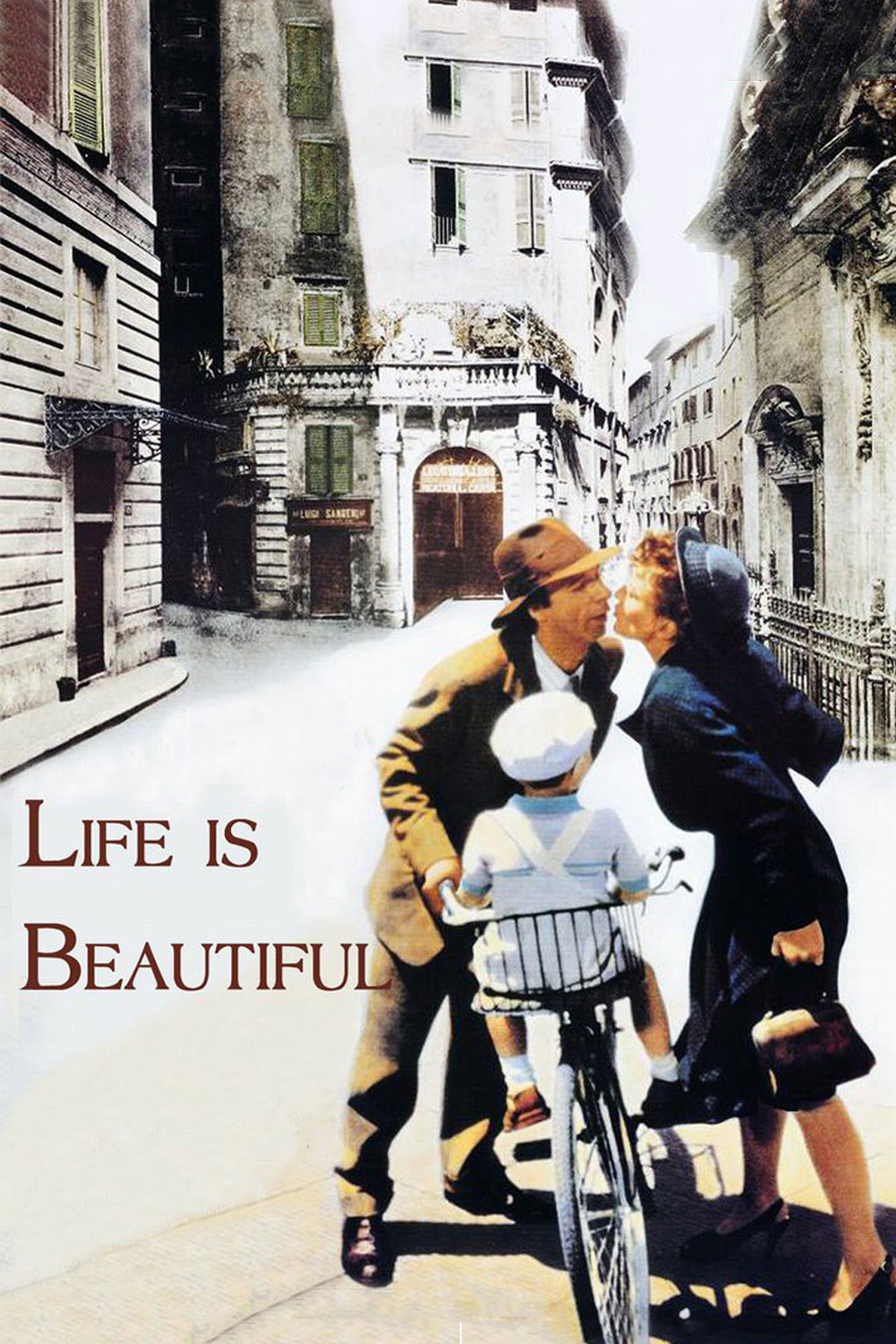

“Life Is Beautiful” is the role he was born to play. The film falls into two parts. One is pure comedy. The other smiles through tears. Benigni, who also directed and co-wrote the movie, stars as Guido, a hotel waiter in Italy in the 1930s. Watching his adventures, we are reminded of Chaplin.

He arrives in town in a runaway car with failed brakes and is mistaken for a visiting dignitary. He falls in love instantly with the beautiful Dora (Nicoletta Braschi, Benigni’s real-life wife). He becomes the undeclared rival of her fiance, the Fascist town clerk. He makes friends with the German doctor (Horst Buchholz) who is a regular guest at the hotel and shares his love of riddles. And by the fantastic manipulation of carefully planned coincidences, he makes it appear that he is fated to replace the dour Fascist in Dora’s life.

All of this early material, the first long act of the movie, is comedy–much of it silent comedy involving the fate of a much-traveled hat. Only well into the movie do we even learn the crucial information that Guido is Jewish. Dora, a gentile, quickly comes to love him, and in one scene even conspires to meet him on the floor under a banquet table; they kiss, and she whispers, “Take me away!” In the town, Guido survives by quick improvisation. Mistaken for a school inspector, he invents a quick lecture on Italian racial superiority, demonstrating the excellence of his big ears and superb navel.

Several years pass, offscreen. Guido and Dora are married and dote on their 5-year-old son Joshua (Giorgio Cantarini). In 1945, near the end of the war, the Jews in the town are rounded up by the Fascists and shipped by rail to a death camp. Guido and Joshua are loaded into a train, and Guido instinctively tries to turn it into a game to comfort his son. He makes a big show of being terrified that somehow they will miss the train and be left behind. Dora, not Jewish, would be spared by the Fascists, but insists on coming along to be with her husband and child.

In the camp, Guido constructs an elaborate fiction to comfort and protect his son. It is all an elaborate game, he explains. The first one to get 1,000 points will win a tank–not a toy tank but a real one, which Joshua can drive all over town. Guido acts as the translator for a German who is barking orders at the inmates, freely translating them into Italian designed to quiet his son’s fears. And he literally hides the child from the camp guards, with rules of the game that have the boy crouching on a high sleeping platform and remaining absolutely still.

At this year’s Toronto Film Festival, Benigni told me that the movie has stirred up venomous opposition from the right wing in Italy. At Cannes, it offended some left-wing critics with its use of humor in connection with the Holocaust. What may be most offensive to both wings is its sidestepping of politics in favor of simple human ingenuity. The film finds the right notes to negotiate its delicate subject matter. And Benigni isn’t really making comedy out of the Holocaust, anyway. He is showing how Guido uses the only gift at his command to protect his son. If he had a gun, he would shoot at the Fascists. If he had an army, he would destroy them. He is a clown, and comedy is his weapon.

The movie actually softens the Holocaust slightly, to make the humor possible at all. In the real death camps there would be no role for Guido. But “Life Is Beautiful” is not about Nazis and Fascists, but about the human spirit. It is about rescuing whatever is good and hopeful from the wreckage of dreams. About hope for the future. About the necessary human conviction, or delusion, that things will be better for our children than they are right now.