“La Sapienza” strikes this reviewer as easily the most astonishing and important movie to emerge from France in quite some time. While its style deserves to be called stunningly original and rapturously beautiful, the film is boldest in its artistic and philosophical implications, which pointedly go against many dominant trends of the last half-century.

Rather than apologizing for or “deconstructing” Western tradition, “La Sapienza” celebrates the West’s spiritual sources to the point that it might be called an apotheosis of European culture. Surprisingly or not, it comes from an American expatriate.

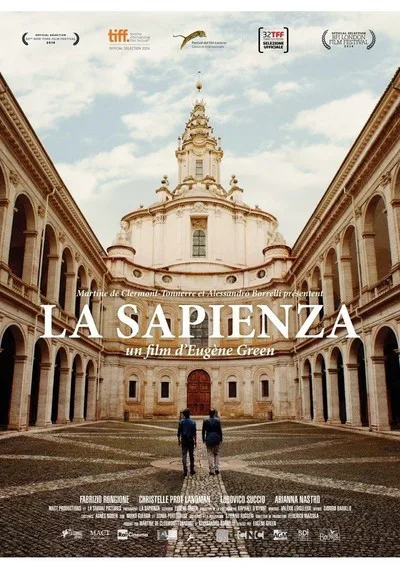

Like Henry James, T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound before him, native New Yorker Eugène Green moved abroad as a young man and became, it would seem, more European than the Europeans. Based in Paris since the ‘70s, he founded a theater company dedicated to the revival of Baroque theater. Since 2001, he has made five features; “La Sapienza,” the latest, is the first to receive American distribution (by Kino Lorber).

It’s worth noting that Green is not a favorite of the French critical establishment (though there seems to be rising support for him among younger critics). That’s understandable given that he has many professed differences with his adopted homeland, beginning with his scornful view that “the official religion of France is atheism.”

A dazzling if unabashedly eccentric work of art, “La Sapienza” has a style that’s immediately striking but so anti-realistic that some viewers may be tempted to laugh at first. Green’s compositions are exceedingly formal and often symmetrical; there’s no clutter anywhere; the lighting recalls old studio movies; characters move in very controlled ways and speak directly to each other or (in p.o.v. shots) the camera. In some ways, there’s a resemblance to the minimalist mannerisms (and spiritual concerns) of Robert Bresson, yet with a kind of theatrical ebullience that also recalls Jacques Rivette and late Jean Renoir.

Green’s allegorical tale meditates on architecture, art, music and history, and there’s no small symbolic significance in the fact that it moves from France to Italy. In Paris, Swiss-born architect Alexandre Schmidt (Fabrizio Rongione) is at a career peak, and professes his staunch belief in materialism and French secularism, but is clearly a desiccated man. Studying sociology and psychiatry has left his wife Aliénor (Chistelle Prod Landman) in a similar place professionally, but she seems less enervated emotionally, so when Alexandre proposes going to Italy to resume research on a book on the Baroque architect Francesco Borromini that he set aside years before, she asks to join him.

On the shores of Lake Maggiore, the couple encounters an Italian brother and sister in their late teens. The girl, Lavinia (Arriana Nastro), has unexplained fainting spells. When Aliénor discovers that her brother Goffredo (Ludovico Succio) wants to be an architect, she persuades her husband to take the boy along on his voyage through Italy in quest of Borromini’s masterpieces while she remains behind and tends to the girl.

Thereafter, the film shifts back and forth between the two sets of characters as a delicate form of communion unfolds in each. Both the architect and his wife, we learn, have suffered tragedies that have left them wounded, guilty and cold. Interacting with their young charges brings them back to life through caring and mentorship. For the wife, this means telling the girl about the blow that has left her marriage desiccated. For the architect, it’s recounting for the boy the story of Borromini’s tumultuous life – a distant reflection of his own – as they traverse Italy looking at his buildings, which are sumptuously photographed as supreme icons of beauty and spiritual expression.

The architect explains the intense rivalry between Borromini and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The latter’s art, he says, is highly rational while the former’s is mystical. Again, the man is telling his own story. “I am Bernini,” Alexandre says, though he obviously aspires to Borromini’s mysticism. In conveying all this to Goffredo, he seems to rekindle a passion and a determination that had been smothered by his adult life’s difficulties and his adherence to the modern orthodoxies of materialism and secularism.

The film’s essential gists, which won’t be strange to anyone familiar with Western mystical thought from Plotinus onward, can be illustrated by reference to a couple of scenes. In one, Goffredo invites Aliénor into his room to see the model of an ideal town he has constructed, one that’s centered on a sacred building called The Temple. She asks what religion it is for, and he says all religions. But what about people who have no religion, she asks. Even they can feel the “presence” that the architect’s use of space summons, he answers. And how does the architect do this? “Through light,” he says.

Later, in Rome, a student tells Alexandre and Goffredo of studying ancient inscriptions. On one stone they found two words in Etruscan for “dawn” and “treasure” above the word “sapienza.” They translated the inscription as, “The treasure of dawn as sapience.”

Sapience, incidentally, generally means wisdom in English. But we never hear the latter word in “La Sapienza”’s dialogue or its subtitles, and sapience appears in various contexts, including the church of Sant’Iva della Sapienza, where Borromini designed a chapel, and the Theatre de la Sapience (Green’s own company of the 1970s), which performs a Molière play that Aliénor and Lavinia attend.

A film of several distinct tonalities, “La Sapienza” takes some droll satiric swipes at the idle rich in Rome and pokes hilarious fun at an Aussie trying to bluster his way into a locked Baroque chapel. In one scene, Green himself appears as a French-speaking Chaldean Christian who’s been chased from Iraq by the American invasion.

Ultimately, though, the film is an impassioned and genuinely innovative argument for the coherence and value of life and the redemptive powers of art. It’s not just Baroque architecture and music that possess such powers, of course. Implicitly Green is vaunting cinema’s own inspiring and transformative capacities when practiced at its highest levels. In so doing, he joins others who appear eager to revive the potency of Europe’s artistic cinema. Like Paolo Sorrentino’s “The Great Beauty” of two years ago and Pawel Pawlikowski’s “Ida” last year, “La Sapienza” evokes masterpieces of decades past while confidently charting new territory of its own. A work of exaltation and profound vision, it deserves to move Green to the front ranks of European auteurs.