In 1990, Madonna brought “Voguing”—an exaggerated dance style started in the underground ballroom scene in Harlem—to the mainstream with her mega-hit “Vogue,” a song that celebrates fantasy and escapism and beauty. Madonna hired dancers she had seen out in the New York club scene, and suddenly, that secret underground world of drag clubs and “Harlem ballroom” was on display at the MTV Awards and in the David Fincher-directed video of the song. That same year, “Paris is Burning,” Jennie Livingston’s documentary about the Harlem dance club and drag scene, won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance. If anyone wondered where Madonna heard about “voguing,” the documentary was the answer. Now, 26 years later, comes Sara Jordenö’s “Kiki,” another deep dive into the same scene. It’s an intimate look at a marginalized community, many of whom rely on the various neighborhood clubs for support systems that don’t exist anywhere else. The so-called “Kiki” scene is not just about the various competitive dance club contests. The scene provides a social structure, a “net,” for kids who have nowhere else to go.

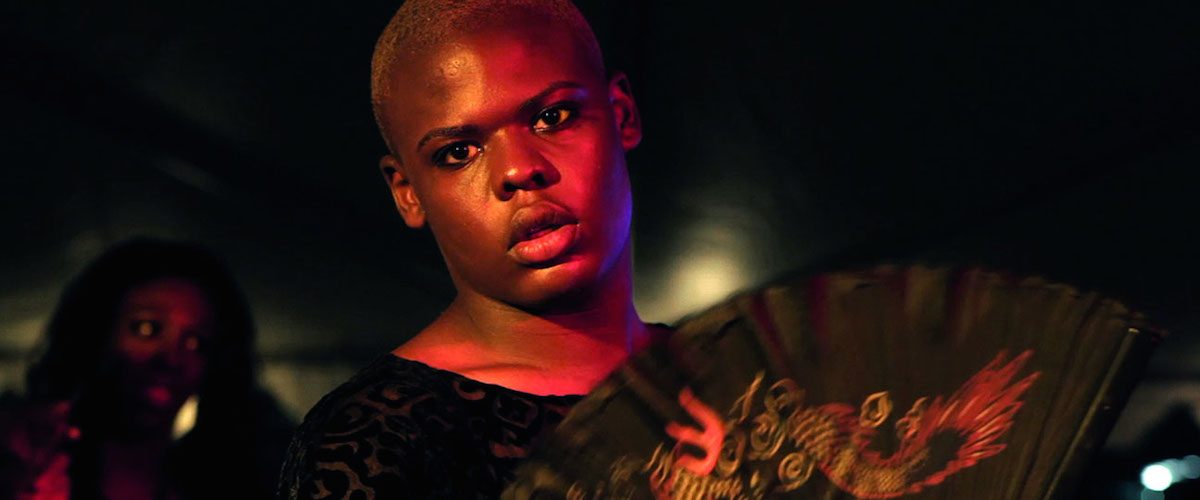

Jordenö, a Swedish filmmaker, collaborated on the film with LGBTQ activist Twiggy Pucci Garcon (he gets a co-writing credit). Twiggy is a highly visible member of the ballroom scene, and his involvement was crucial in terms of providing Jordenö access to a community that is highly protective (with good reason) of its members. The documentary has a high-energy and full-immersion style that thrusts you into the center of the various “houses” connected to the scene. Each “house” has a team that competes in the dance competitions. The dance competitors are mostly queer and trans people of color, and “Kiki” introduces you to many of them. “Kiki,” with all of its group scenes (kids Voguing on the Chelsea piersa common hangout, the raucous competitions themselves), is really a character-driven narrative.

While there are similarities in many of their stories, each journey is different. Many of the young adults profiled have been kicked out of the house for being trans, queer, or just gender-nonconforming. They have gravitated towards one another, and immersed themselves in a culture that is nonjudgmental, open, and caring. They take care of each other. They crash on each other’s couches. They have each other’s collective backs. “Paris is Burning” highlighted the struggles of queer kids in the Reagan/Bush era, and “Kiki” shows the anxiety of the scene at the tail-end of the Obama years. Many of these people depend on federal funding. They are among the most vulnerable members of our society. They already experience an onslaught of harassment from family, peers, police. Many of them have fallen into addiction or sex work. There are support groups sponsored by each house, where people can talk openly about these issues.

Twiggy is one of our main ways “in” to this closed scene, and you see him running warm-ups for rehearsals, and keeping everyone in line, reminding them of the stakes in the competitions. He is an activist, working for the homeless LGBT youths in his community, helping to provide structures of support and relief. Gia Marie Love emerges as the star of the film, however: a trans woman who has transformed herself from a bullied youth into a leader in her community. Watching her run a support group, it’s not hard to understand why she was a debate club champion in high school. There’s the soft-spoken Divo, kicked out of the house by his mother, who was—as he admits freely—saved by the ballroom scene.

One thing “Kiki” does really well is show how these dance competitions are an organizational structure for kids who might otherwise slip through the cracks. Everyone makes their own costumes, which are fantastical and outrageous. Taking place in school gyms and community halls, it’s a safe space where people can let loose and express themselves, with no fear of harassment or rejection. This is a scene that takes care of its own. In many cases, it’s literally life or death.

Jordenö makes a couple of directorial choices that repeat throughout: each person is seen standing on a city sidewalk, a pier, a street corner, staring directly at the camera, a vision of stillness that stops the film in its tracks, giving us a chance to breathe, to look. There are also a couple of scenes shot in an empty theatre, where the various dancers, bathed in blue light, show their stuff. It provides another perspective of these street kids, their ability to translate their fantasies of themselves into movement, elegant and elongated and exaggerated.

The full-immersion style has its drawbacks. The characters are introduced early on, those the film will follow, but biographical details and “confessional” comments come late in the documentary. It takes a while to understand what is happening, and who is who. The jostle of names and information and intersecting relationships is a confusing bombardment.

With music by Qween Beat, “Kiki” shows the new generation of the ballroom scene, their care for one another, their awareness of the struggles ahead, their determination to be themselves, against all odds. They are scared, but they are strong. They know what is right and they fight for it. “Kiki,” with all its rough glamour and rambunctious dancing, is a political film. These kids live it.