“In the Family” centers on one of the notable performances I’ve seen — if, indeed, it is a performance. Perhaps Patrick Wang is exactly like that. Then he must be a very good man. He wrote, directed and stars in the film, but it’s not a one-man show. It is about the meaning of “family.” This is his first feature, and may signal the opening of an important career.

Wang plays Joey Williams, a Chinese-American man who has been living happily for about five years with Cody Hines (Trevor St. John) and Cody’s 6-year-old son, Chip (Sebastian Banes). Chip’s mother died in childbirth. Some months after that, to his own surprise, Cody fell in love with Joey, and they’re raising Chip. This household is given enough screen time to establish it as a happy, healthy place.

Then Cody is killed in an accident. Chip stays with Joey, whose treatment of him is a study in wisdom and love. The boy is so irrepressibly joyous that we sense what a happy life he has led. But Cody’s sister Eileen (Kelly McAndrew) reveals that her brother left a will years ago, granting her all of his property and custody of his child. This will, written after the death of Cody’s wife and before he met Joey, has never been updated.

On Thanksgiving Day, Joey drops the boy off at the sister’s house and never sees him again. A lawyer in his Tennessee town tells him flatly he doesn’t have a child custody case, and no judge in the state will rule in his favor. Neither this lawyer nor anyone else ever uses the words “homosexual” or “gay.” It isn’t in any sense a “gay rights” film, nor is it an “Asian-American” film. It is about a father and son who have been separated against their wishes.

Its objectivity in these terms is possible because of Wang’s extraordinary performance. I’ve been unable to discover any details about him, but he speaks in a relaxed, natural Tennessee accent and creates Joey as a particularly convincing character, a contractor who drives a red pickup truck. (Cody was a schoolteacher.) His own parents died when he was very young. He was adopted by foster parents, who gave him their name, and who died when he was a teenager. As a man of Asian birth who has been raised apart from other Asians, as an orphan and a foster child who for years had no family, we sense how important stability and continuity are to him.

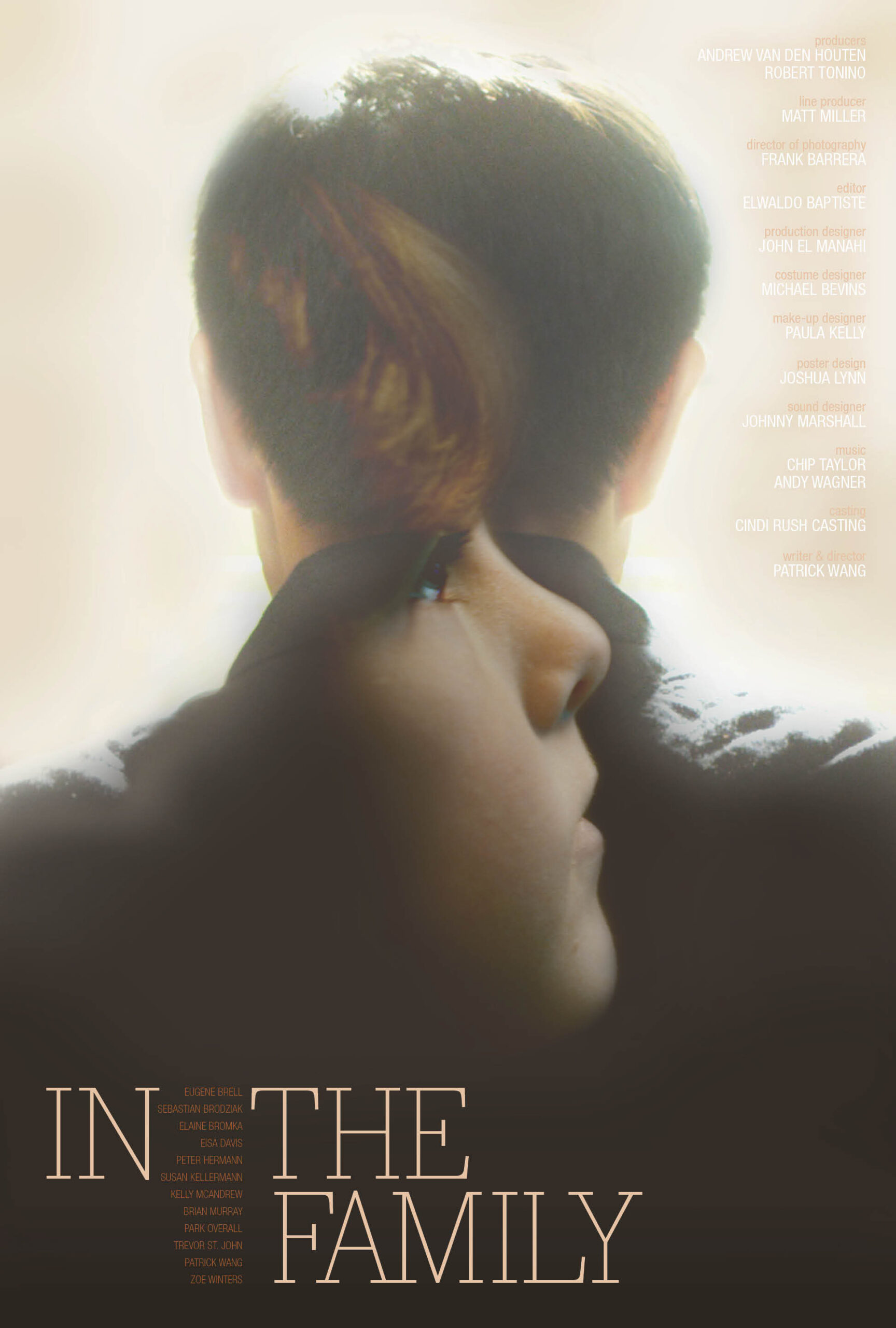

And there is something else. Without ever making a point of it, he has been treated as an outsider. Wang, as director, indicates this by several scenes with the back of the character’s head to the camera, so that we see the other characters from his POV, instead of seeing Joey mixed in visually. He is not a hothead, not neurotic, not psychologically damaged, but in this crisis, the entire basis of his being has been challenged. Having seen Cody, we can feel certain he would have granted custody to Joey if he had ever made another will. Cody’s sister doesn’t see it that way. What does she think about homosexuality? She never says.

Joey’s case looks hopeless. Friends try to console him, but helplessly. He’s working on a house for a local attorney who has an ornate law library, and he reveals his skills in bookbinding — an art learned from his foster father. This attorney, Paul Hawks (the authoritative and wise Brian Murray), offers his help and observes there may be no help within the court system but there may be a more human path around it.

Then follows a scene of legal depositions, during which Patrick Wang’s performance, in long takes that feel entirely spontaneous, recounts his life story. Joey’s response to the offensively hostile attorney for the other side is masterful: He humiliates the other man simply by being a good person and telling the truth.

“In the Family” is a long film, and truth to tell, could have been made shorter. (One dimly lit confrontation between Joey and a key participant seems unnecessary.) That said, I was completely absorbed from beginning to end. What a courageous first feature this is, a film that sidesteps shopworn stereotypes and tells a quiet, firm, deeply humanist story about doing the right thing. It is a film that avoids any message or statement and simply shows us, with infinite sympathy, how the life of a completely original character can help us lead our own.