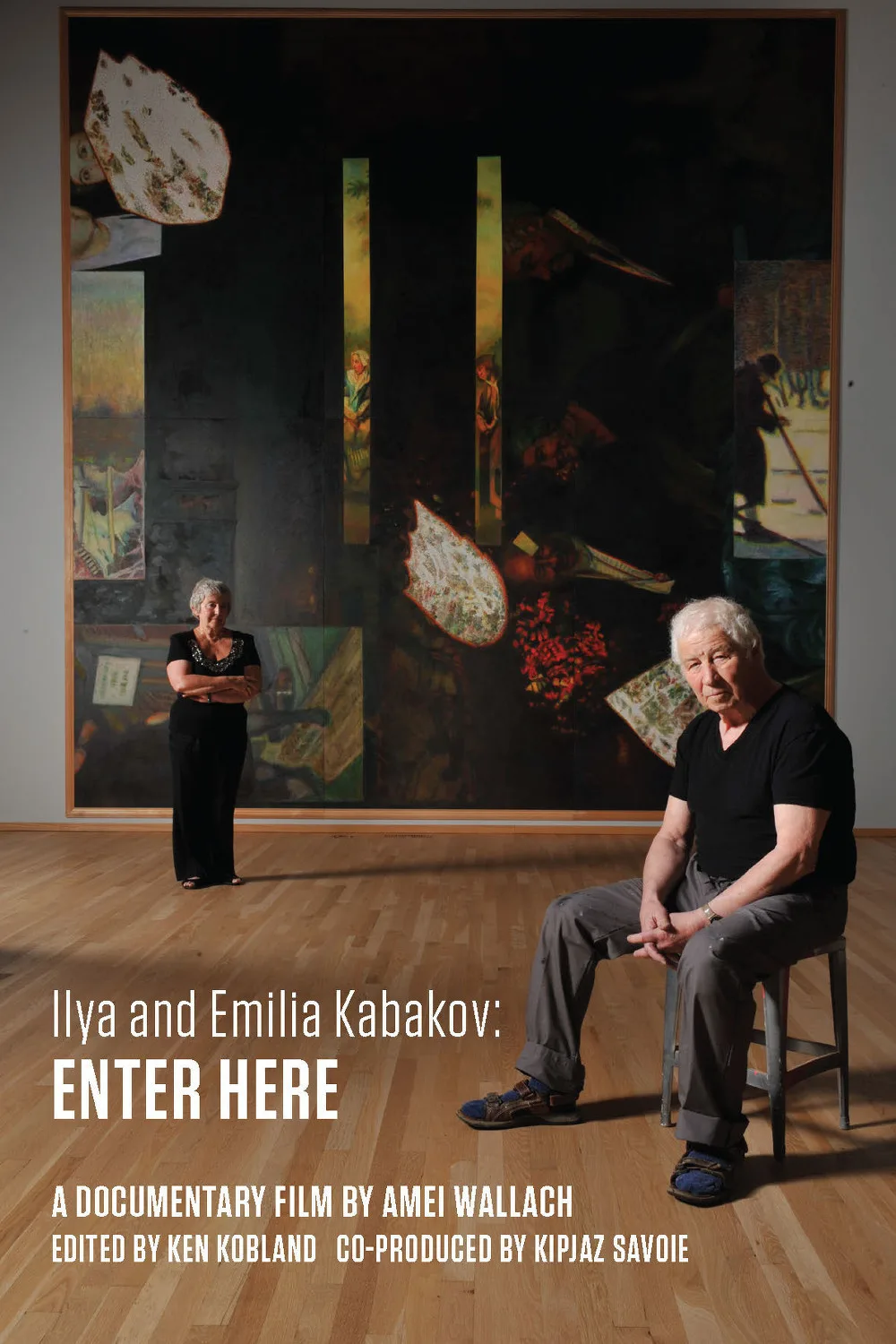

Ilya Kabakov, 80 years old, internationally-renowned artist, speaks of the “labyrinth” of some of his work (and, indeed, one of his installations is titled “The Labyrinth”), where as you move through the space you forget where you are, you forget the way out, and only in that disorienting context can you finally perceive that “art is important”. An installation artist whose works are often gigantic, encompassing entire buildings, Ilya Kabakov looks for his work to be a “total installation”, a full-immersion experience where any distance between artist and viewer is eradicated. Filmmaker and art critic Amei Wallach takes us through Kabokov’s various labyrinths in her beautiful new documentary “Ilya and Emila Kabakov: Enter Here”. It is both a portrait of Ilya and his wife and partner, Emilia, as they put together a gigantic installation in Moscow (his first return to his home country after emigrating in 1987), as well as an exploration of Ilya’s influences and journey as an artist through 20th century Russia.

Born in 1933 in the Ukraine (an “annus horribilis” for the Ukraine if ever there was one), Ilya was the only child of a doting selfless mother, whose sacrifices still bring tears to Ilya’s eyes almost a century later. In 1941, mother and son fled to Samarkand to avoid the war. Ilya was a child, but The Leningrad Academy of Art just happened to have been re-located to Samarkand for the duration of the war, and it was there that Ilya got his start as an artist. He transferred to a school in Moscow. His mother, who did not have a residency permit for Moscow (essential to move around freely) was reduced to sleeping in public toilets and camping out in kindly people’s homes (always a gamble: she was reported to the authorities numerous times). When she was an old woman, Ilya asked his mother to write down her life story for him. She complied and filled up a notebook with her memories, which he has turned into some of his most emotional installations.

The event around which the documentary is organized is a huge retrospective installation of his work (spread out in three different venues) in Moscow in 2008. Returning to Russia after so many years in the West was an emotional powder-keg for this sensitive man. Kabakov was uncertain as to how his work would be received by a younger generation who grew up after Communism fell. How would they see his explorations of communal life and collectivization, his critiques of the bureaucracy and conformity and propaganda? Would it have resonance for people who did not experience it? Kabakov’s work is so intricate that it requires electricians and cement workers and construction gangs to put it together. We see Ilya pacing around in the warehouse in Moscow, worrying, lost in thought, as his wife Emilia works the phone and makes things happen. It’s a powerful partnership.

There’s a lot of material here to get through, and Wallach and her cinematographer Ken Kobland take their time with it, a gamble of an approach which works, on the whole. Its greatest strength is in the filming of the installations themselves. The camera floats up and around and through the various works, letting us perceive them from all angles. We see it in its entirety, we move through the different rooms, we zoom in on this or that detail. It is as close an approximation as to what it would feel like to be there in person. Underlying this is sometimes a voiceover from Ilya or Emilia, telling us the ideas behind the projects, but sometimes, as with the spectacular “The Red Wagon” installation, built at “The Garage” in Moscow, there is just a melancholy violin accompanying the moving images onscreen. The approach leaves you room to interpret what you are seeing for yourself.

What interests Kabakov is the two-faced nature of Soviet life, the divide between the public face (dominated by the State and its propaganda fantasies) and the personal life going on behind closed doors. Doors are essential symbols: they represent privacy, first of all, something in small supply in a state where the KGB sets up art galleries in order to keep its eye on the avant-garde artists who flock there. But doors also represent entryways into other people’s experiences, other eras, other lifetimes. Many of his installations are multi-roomed structures, with doors leading you further and further inside. Emilia Kabakov suggests that her husband grew up feeling that he was an “outsider”, and his outsider status is reflective in his work. He was an “unofficial” artist, meaning unsponsored by the State, and therefore worked in obscurity for many years. Soviet society was a closed door to him. Ilya Kabakov is clearly traumatized by Russia (on his return to St. Petersburg in 2008, he was so freaked out he didn’t want to leave the hotel), and yet, as Emilia says of him: “He thrives on negative emotions. It provokes him to do something interesting.”

Looking at his work, it becomes obvious why the Artist is so often the first one on the chopping block in any dictatorship or totalitarian society. Without being explicit, without being overtly angry, Kabakov’s installations are a critique of the entire system, a critique leavened with irony, wit, and fantasy. It’s powerful stuff. You go into Kabakov’s labyrinths of associations and you don’t come out.