The great hall in Jean Epstein’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” is one of the most haunting spaces in the movies. Its floor is a vast marble expanse, interrupted here and there by an item of furniture that seems dwarfed by the surrounding emptiness. An odd staircase rises from one distant corner. It is not impossible that this vision, in one of the best-known French surrealist films, inspired the designers of the great hall of Xanadu in “Citizen Kane.” In both films, shadows are made to substitute for details that are not really there, and a man and a woman, their lives ruled by his obsession with her, move like wraiths through the haunted space.

The hall is not simply cold, enormous and forbidding, but has surrealistic details. “Leaves blow ominously across the floor,” writes the critic Gary Morris, and the long white curtains “flutter menacingly, as if the house is under constant, quiet, insidious siege by a vengeful nature.” This is not a room for human habitation, but a set for a surrealist opera.

The occupants of the house are Roderick Usher and his young wife, Madeline. In the original story by Edgar Allen Poe, they were brother and sister, but the implication of incest has been removed by Epstein, who explains with a title card that the men of the house of Usher have all been obsessed with painting their wives. Roderick is consumed with fear that his wife will die, and no less fearful that she will be buried alive. Does he hope that his portrait will transfer her essence to a form that will live forever?

To the house an unnamed friend is summoned. There are echoes of the Dracula films and of the silent classic “Nosferatu” (1922) in the way the locals refuse to convey the visitor to the house, even though poor Roderick Usher is merely demented, not vampirish. The friend’s arrival is curiously staged, with Roderick standing at the top of a flight of steps and leaning far forward to extend his hand to the other man, but apparently not daring to take even one actual step down to approach him. An umbilical cord seems to tie him to the interior.

The exterior of the house, seen in the midst of the obligatory blasted heath, is obviously a drawn miniature, and critics point out the unconvincing stars in the sky, proudly fake. This kind of obvious artifice, which hardly even attempts to fool the eye, owes something to the German expressionist tradition in films like “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” Although the interior of the house looks more real, or at least more physically present, its nightmare details and vistas are also less concerned with realism than with effect.

Epstein’s assistant director on the film was young Luis Bunuel, who had just finished his notorious collaboration with Salvador Dali on “Un Chein Andalou,” a boldly surrealist film. Did he contribute to this film’s weirdness? No doubt, although Epstein was a surrealist himself and the underlying story itself is less interested in psychological plausibility than in the creepiness and oddness of its immediate impression. (Bunuel eventually quit after a quarrel with Epstein.)

Roderick is played by Jean Debucourt, more convincing than many silent stars, who goes less for the demented madman effect and more for the aura of a man consumed by his fears. Madeline is played by Marguerite Gance, wife of the French director Abel Gance (“Napoleon”). Her task is to be an object. All attention and animation is concentrated in the two men, while Madeline poses for her painting and slowly sinks toward the grave. The visitor and narrator is Charles Lamy.

There is an amusing ambiguity about the painting, which we see at regular intervals throughout the film. In some shots it is a real canvas, which Roderick daubs at. In others it is the real Marguerite Gance standing within the frame and pretending to the camera she is the painting. “In a motif lifted from Wilde’s ‘Picture of Dorian Gray,’ ” writes the critic Mark Zimmer, “her life and vitality pours into the painting, such that it begins to blink and move, as she dies.” Perhaps, but not according to the critic Glenn Erickson, who writes, “Roderick’s portraits are represented by having Madeline sit very still behind the frame and pretend to be a painted image. Unfortunately, she blinks in almost every take, ruining the illusion.”

Both critics are seeing exactly the same thing. Which critic is correct? The surrealists would have been delighted by the confusion.

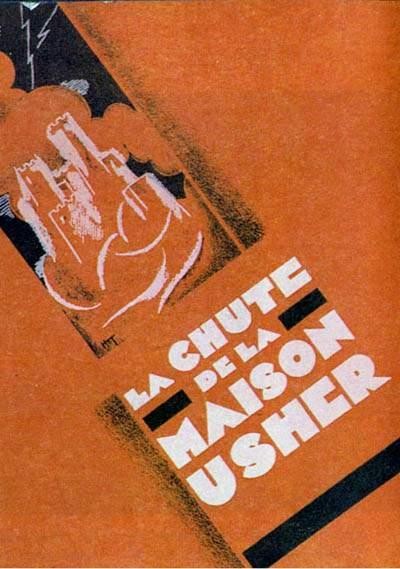

Jean Epstein (1897-1953), born in Poland, studied medicine before falling into the Parisian orbit of the surrealists in the 1920s. He directed films throughout the 1920s, finding as others did that silent films gave themselves naturally to fantasy and impressionism; the talkies would discover that dialogue tended to tilt stories toward realism. “The Fall of the House of Usher,” made in 1928, the last great year of silent films, was based on a Poe story that is more atmosphere than plot, anyway. There have been many versions of “Usher,” from another 1928 silent film through to Roger Corman’s excellent 1960 version with Vincent Price. Epstein seems to focus less on the mechanics of the situation than on its very oddness: The man and woman both trapped by his mad obsession with death, the woman almost helpfully fading away.

I was struck, watching the film recently on a new DVD, by how completely it engaged me. Some silent films hold you outside: You admire them, but are aware of them as a phenomenon. With “The Fall of the House of Usher,” I barely stirred during the film’s 66-minute running time. A tone, an atmosphere, was created that actually worked. As with “Nosferatu,” the film seemed less a fiction than the realization of some phantasmagoric alternative reality. Epstein’s openness to the grand gesture is helpful, as when Madeline is in her coffin, and her white bridal veil spills outside and blows in the wind.

Two modern additions to the film also enhance it. Instead of replacing the original French titles and their boldly stylized calligraphy, this version uses the voice of actor Jean-Pierre Aumont to read them in English. The effect is that the titles are as real as the film, and Aumont is standing outside of it, next to us, confiding the horror they contain.

The other addition is the score from 1960 by Rolande de Cande. Based on medieval music, composed for woodwinds and strings, it is an extraordinary piece of work. It feels as if it emerges from the images themselves, odd, sad and vaguely liturgical.

Characters in horror films tend to pose. They are presented not in terms of complex human nature, but within the narrow definition of their obsession, or weakness, or limitation. Stories often involve an outside visitor whose function is to provide an audience and, later, a report. The story of Roderick and Madeline would be less dramatic if there was no one there to witness it and provide the reaction of a normal person. Yet more than many horror characters, Roderick and Madeline seem complete in their drama, as if they do not need the observer. Roderick thinks only of death, decay and the Poe’s beloved dread of being buried alive. And Madeline–well, why did she marry him? What was their courtship like? Has it ever occurred to her to simply walk away? One does not ask such practical questions about a horror film, I know, but Marguerite Gance succeeds in suggesting that Madeline has fallen under the spell, whether willingly or not, and is also caught up in the obsession.

There are times when I think that of all the genres, the horror film most misses silence. The Western benefited from dialogue, and musicals and film noir are unthinkable without words. But in a classic horror film, almost anything you can say will be superfluous or ridiculous. Notice how carefully the Draculas of talkies have to choose their words to avoid bad laughs. The perfect horror situation is such that there is nothing you can say about it. What words are necessary in “The Pit and the Pendulum”? “The Fall of the House of Usher” resides within its sealed world, as if–yes, as if buried alive.