Eventually the veterans in the rifle squad stop bothering to learn the names of the new kids who arrive to bring them up to strength. They get killed so quickly, it’s not worth the trouble. But the sergeant and four of his men make it all the way through the war, or almost, anyway — from North Africa to Sicily to Omaha Beach on D-Day to Belgium and finally to Germany and the liberation of a death camp.

Is it unlikely these five would be survivors? Not to Sam Fuller, who wrote and directed “The Big Red One” (1980), based on his own combat memories. “I wanted to do the story of a survivor,” he told me when the movie premiered at Cannes, “because all war stories are told by survivors.”

Fuller was a cigar-chomping, tough-talking, wiry little guy who started out as a teenage New York crime reporter, lying about his age to get the job. He wrote pulp novels, he talked tough, he fought all the way through the war, and he carried around memories of the First Infantry Division, the “Big Red One.” He made a lot of other movies first, hard-boiled war movies like “Steel Helmet” and “Fixed Bayonets” (both 1951), noir classics like “Pickup on South Street’ (1953) and cult B pictures like “Shock Corridor” (1963) and “The Naked Kiss” (1964).

Finally he got his chance at his dream project. He had a limited budget, $4 million, but he shot and shot and shot, because like all newspapermen he couldn’t bear to waste a good story. Yes, the movie is episodic. War is episodic. He said he couldn’t stand war pictures that had a story arc where everything led up to a big scene. In the real war, you lived in the present. There was no connection between what happened to you last week and what was happening today, because you had no direction over your life and neither did anyone else.

Fuller’s original cut of the film came to 270 minutes. It was cut to 113 minutes, which broke his heart, but what was left worked well enough that he was proud of it. He talked about restoring his original version, but he died in 1997 without getting that done. Now the film critic Richard Schickel has overseen a reconstruction that brings the film up to 158 minutes, and it reveals a richness and pacing missing in the earlier version; one suspects that the 270-minute version was a rough cut even Fuller would have trimmed. The restored “Big Red One” is able to suggest the scope and duration of the war, the way it’s one damned thing after another, the distances traveled, the pile-up of experiences that are numbing most of the time but occasionally produce an episode as perfect as a short story.

Fuller centers everything on the sergeant, played by Lee Marvin with the rock-solid authority of a man who had seen action as a Marine in the Pacific, and called his other big war movie, “The Dirty Dozen,” a “dummy moneymaker.” Fuller always wanted Marvin for the role. A studio insisted on John Wayne, but Fuller said he’d rather not make the picture. He was correct. This is Marvin’s picture, and he dominates it not with heroics and speechmaking but with competence, patience, realism, and a certain tender sadness. There’s a scene where a soldier is shot in the groin, and the sergeant finds something in the mud and tosses it away: “That was just one of your balls, Smitty. That’s why they give you two.”

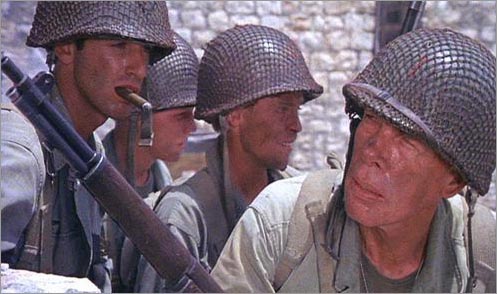

The long-lasting squad members are Zab (Robert Carradine), a cigar-chewing pulp writer who is obviously playing Fuller; Griff (Mark Hamill), who doesn’t like killing but has a change of heart; Vinci (Bobby DiCicco) and Johnson (Kelly Ward). There’s a scene where one of the anonymous new replacements is reading a paperback titledThe Dark Deadline,and Zab tries to tell him he wrote the book. The kid doesn’t grasp the concept. He’s dead before he finishes the book.

The film starts with the horror of World War I, as a shell-shocked Army horse runs maddened across a battlefield. That’s where we meet Marvin’s character for the first time. He apparently becomes a lifer in the Army, is promoted to sergeant, leads these kids through the next war. We learn nothing about him — not if he’s married, not if he has a family, not even his name. In another sense, we learn everything about him. Fuller and Marvin never give the sergeant those obligatory campfire speeches describing his history and beliefs, and instead develop the character by showing how he behaves at important moments. He captures a German sniper, for example, and finds out the gunman is only a kid from Hitler’s desperate last-ditch “children’s army.” The sergeant would have routinely shot another sniper. This one, he spanks.

There are details Fuller must have remembered from the time, such as the landing in Africa at a position defended by soldiers from the Nazi-sympathizing Vichy government of France. “If you’re Vichy, fight us,” the Americans shout over loud-speakers. “If you’re Frenchmen, join us.” The scene draws a class distinction between officers and men in the French lines. There is no distinction between the American sergeant and his men.

Some episodes sound like something Fuller would tell you over a beer. Like the time the squad hides in a cave and one German after another appears in the opening — some to pee, others to have a look. The Americans pick them off one by one. They’re in desperate danger themselves, but the cave becomes their shooting gallery. And there’s a scene where they deliver a baby in a German tank they’ve just captured; in his heartfelt review of the film, Charles Taylor of Salon.com notices “one genuinely surreal detail: hanging belts of ammunition used as stirrups, the bullets pointed at the pregnant woman’s belly.”

There is a moment during the landing at Omaha Beach that no one forgets after seeing the film. A soldier’s arm has been torn off, and sticks in the sand, a wrist-watch still in place. From time to time, Fuller cuts back to the watch; we can see how much time has passed. Steven Spielberg, who undoubtedly screened “The Big Red One” while preparing “Saving Private Ryan,” is not a director who often needs to feel envy, but he must have coveted that shot.

What we understand, finally, is that the entire war comes down to these five men, because it istheirentire war. Nobody wades ashore with 10,000 men. They wade ashore all by themselves. By limiting the scope of the action, Fuller was able to make the movie look completely convincing on his limited budget, using Ireland for the scenes set in Belgium and Israel for all the other scenes. We see tanks and planes and Germans and landing craft when we need to, but the focus is on the faces of the squad members.

Talking with Fuller, I quoted Truffaut’s dictum that all war movies are pro-war, because no matter what their “message” is, they make the action look exciting.

Fuller snorted. “Pro or anti, what the hell difference does it make to the guy who gets his ass shot off? The movie is very simple. It’s a series of combat experiences, and the times of waiting in between. Lee Marvin plays a carpenter of death. The sergeants of this world have been dealing death to young men for 10,000 years. He’s a symbol of all those years and all those sergeants, no matter what their names were or what they called their rank in other languages. That’s why he has no name in the movie.

“The movie deals with death in a way that might be unfamiliar to people who know nothing of war except what they learned in war movies. I believe that fear doesn’t delay death, and so it is fruitless. A guy is hit. So, he’s hit. That’s that. I don’t cry because that guy over there got hit. I cry because I’m gonna get hit next. All that phony heroism is a bunch of baloney when they’re shooting at you. But you have to be honest with a corpse, and that is the emotion that the movie shows rubbing off on four young men.”

Yes, it does. And that’s why Griff, the squad member who doesn’t like killing, pumps 20 rounds into a Nazi in one of the final scenes. He is a killer, shooting at a murderer.

Ebert talks with director Fuller at Cannes in 1980.