Céline Sciamma’s films are delicate and emotional examinations of, to quote Madonna, “what it feels like for a girl.” Sciamma has directed three features thus far: “Water Lilies,” “Tomboy,” and now “Girlhood” and each one takes on a different sliver of the spectrum of adolescent or pre-adolescent girlhood. Girls are not a monolith, they are not all the same, they are not “the other,” although you’d never know it considering some of the films out there. It takes an intuitive and devoted filmmaker like Sciamma to go beneath the surface of “girlhood”, to remove the normal trappings, and to look at all of the different forces and influences in play. “Girlhood,” her latest, is a powerful and entertaining film about a gang of girls, and what friendship means, the protection it provides.

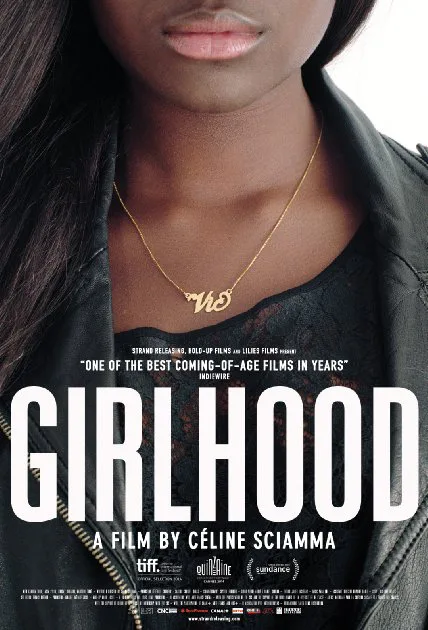

“Girlhood” follows Marieme (the extraordinary Karidja Touré) through her 16th year. She lives in a big housing project, and is the main caretaker of her younger sister. Her grades are poor and she is being pushed to transfer to a technical school and learn a trade. Her mother (Binta Diop) works so many jobs she is never around, and Marieme has to answer to her brother (Cyril Mendy), who is downright abusive. Marieme is a sweet and shy girl, her hair falling down her back in braids. One day three tough Rizzo-types, lolling on the bleachers, summon her over to their pow-wow. Their motivations aren’t clear at first. Marieme seems much younger than these glamour girls, all of whom wear long straight weaves, identical gold necklaces, and red lipstick. The cliche is that the “bad girls” will “corrupt” the good girl. But Sciamma is up to something different, thank goodness.

These three girls are Lady (the wonderful Assa Sylla), the leader of the pack, and the two humorous underlings, Fily (Mariétou Touré) and Adiatou (Lindsay Karamoh). They need a “fourth” to round out their group. They’re trouble-makers, engaged in fighting with another group of girls; nothing too serious, just a lot of screaming insults across train platforms. Marieme enters the group dynamic: the four girls hustle, they shop-lift, they book hotel rooms and eat pizza. The gang of girls do not initiate Marieme into a dangerous world of drugs and sex. No, the tough girls initiate her into a world of belonging, of fun trash-talk, an environment where she can let loose, try on makeup and a different hairstyle (for her friends’ benefit, not for any romantic prospect’s benefit), and experiment a little bit with identity. The new persona might not “fit” Marieme, ultimately, but she’s 16 years old. She’s figuring it out.

Life is tough out there, and the girls are aware of it. There are pimp-type guys starting to show interest in them, circling like sharks. There are judgmental fathers and brothers, who shame the girls for growing up, for wanting to stretch their wings a little bit, sexually. Marieme starts to date, tentatively, a boy she’s known forever, named Ismaël (Idrissa Diabaté). Their scenes together offer a sweet space where both can allow themselves to be tender, in contrast to the closed-up toughness required in their larger world. They click. But it feels precarious. The girls watch their friends get knocked up and, for all intents and purposes, vanish from the world. They don’t want that for themselves. They want … something else, something more. Freedom. Liberty. To be left alone.

What Sciamma is interested in is “moments.” There are many moments that linger in the mind long after the film has ended. The epic slo-mo all-female football game of the opening. An early scene showing a raucous group of girls heading back to the projects, all talking at once, until they fall into silence, collectively, when they approach a group of boys lounging on the steps. The repeat shots of the back of Marieme’s head throughout, breaking “Girlhood” up into unofficial “chapters.” Marieme washing dishes, emerging into the concrete yard outside, the camera following her, her head facing out. (Sciamma started “Tomboy” with the back of a head as well, a head with shorn-short hair, looking away, creating an automatic confusion as to whether it was a boy or a girl, the whole theme of the film.) In “Girlhood,” there are fight scenes and a hilarious miniature-golf excursion, as well as many painful reminders that no, they will not be left alone, the world cannot leave the girls alone.

A masterpiece scene comes halfway through, so powerful in its representation of shared joy and freedom that it sets off echoes around it that continue throughout the rest of the film. The girls have shop-lifted pretty dresses, and booked a hotel room where they can hang out for the night, maybe go out to a club later in their stolen goods. There’s a sense of exhilaration in the moment, and the four get up and start dancing together to Rihanna’s “Diamonds.” The light is a deep blue, and the girls are jumping and laughing and loving each other’s awesomeness for almost the entirety of the song. All four are in the frame at the same time. Sciamma has given us what feels like a real event, a real moment, one of those precious moments in time that the girls might look back on and think, “That. That was good.”

The final section of “Girlhood” doesn’t quite have the energy of the rest of it, although Karidja Touré is such a compelling presence, and Marieme is such a watchable character, that her experiences create a tension all their own. What will become of Marieme? The group friendship is formative, powerful, for all of them, it is something they treasure and cling to, but they’re also just teenage girls. They’re not sure yet what is going to be the most important thing in their lives.

Comparisons will be made, inevitably, to Richard Linklater’s “Boyhood,” merely because of the title. They are two very different films. Sciamma’s films could all go under the title “Girlhood.” Her films do not diagnose. They don’t worry (at least not overtly). They do not assume that “girlhood” is mostly an experience of inevitable derailment. Adolescence is a time of growth and change, of trying on new identities, seeing which one fits the best. Girls “come of age” just like boys do, but many films take the attitude that it’s more dangerous for girls to experiment. That might be partially true, because of pregnancy, but it is not entirely true. “We Are the Best!” was a terrific antidote to that prevalent teenage-girls-in-peril narrative, and so is “Girlhood.” It’s not that Sciamma sugar-coats the dangers that are out there. It is that she is more interested in how girls figure things out than in the many ways girls can go wrong.