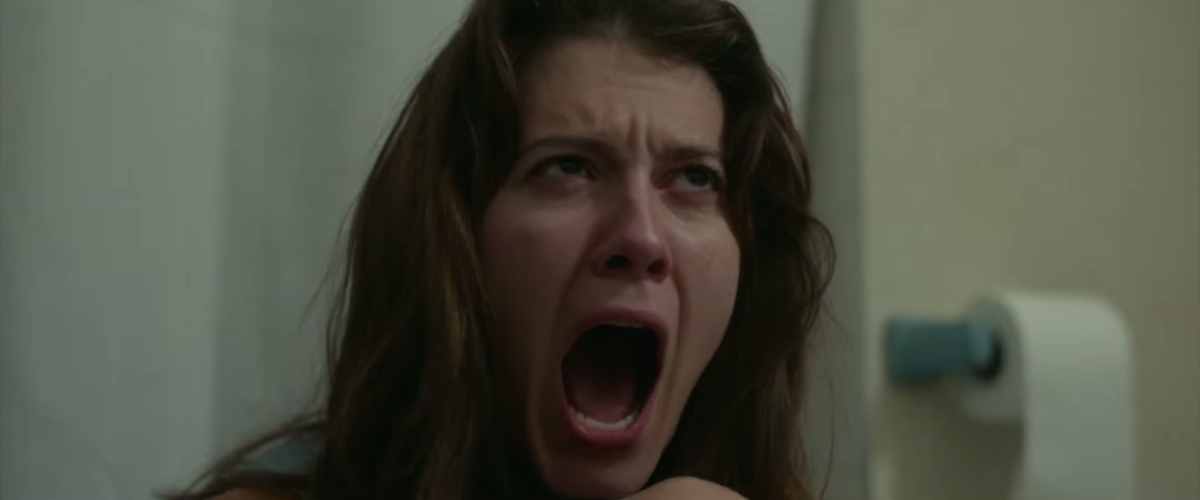

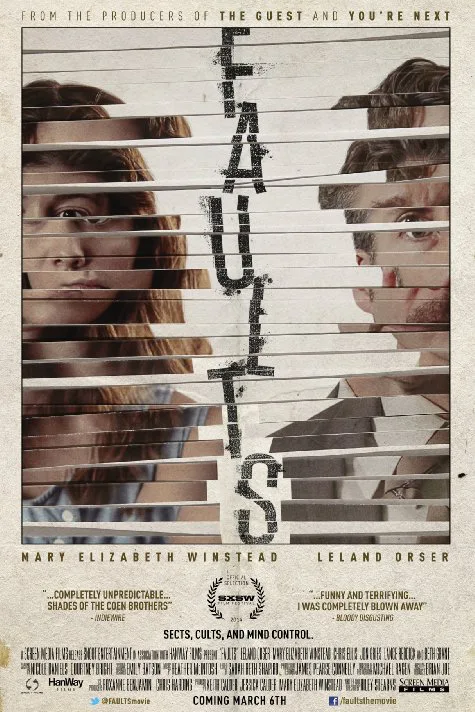

The key to enjoying “Faults” is to look at it as a mood piece. “Faults” is not just a character study about Ansel (character actor Leland Orser), a desperate self-help guru. And it’s not just a black-comedy/thriller about what happened to Claire (Mary Elizabeth Winstead, who also produced the film), a young cult victim, after she joined Faults, a secretive religious organization.

“Faults” is a richly-textured movie that concerns the weird space between thinking you know what you’re doing, and actually knowing what you’re doing. You watch it, and marvel that a film that seems to be about Ansel’s dogged attempts at re-integrating Claire back into society is less about story, and more about tone. “Faults” is a mystery that doesn’t stop being mysterious once it commits to its schematic finale. Even then, the spell that writer/director Riley Stearns casts doesn’t completely dissipate. Stearns’s film works as well as it does because he puts you in his characters’ shoes, and makes you revel in their disorientation.

“You are free,” Ansel distractedly tells a small hotel conference-room-full of disinterested attendants, a line he seems to have delivered a million times before, and is still finding his way into. Ansel’s not much of a motivational speaker, but that line rings true. “Faults” is, after all, a movie about potential: you watch and realize that this desperate man’s story could easily change course at any moment. Which is fitting since Ansel specializes in “de-programming,” an anti-brain-washing process that helps religious cultists to re-assimilate by challenging their zealous beliefs.

Ansel’s not a naturally confident man, as we see in the scene where he half-heartedly tries to kill himself by inhaling carbon monoxide fumes from his car–while his car’s parked in an open-air parking lot. But his strategy for breaking Ansel down is sound: over the course of five days, Ansel shows Claire that she doesn’t need any one thing to define her. She is more than her religion, her clothing, her family, etc.

The freedom that comes with that knowledge is both liberating and terrifying. Which is why “Faults” constantly teeters on the edge of broad humor, and grim drama. Orser’s performance captures that balancing act mix perfectly. In any given scene, he subtlely transforms from a buffoonish cheapskate into a sympathetically fallible do-gooder. There’s an early scene where Ansel addresses Claire’s parents, and he’s begging them to leave him alone. And the desperation in his eyes drowns out the bold-faced, declarative nature of Stearns’s dialogue. Here you can clearly see the extent of Ansel’s loneliness, just like how you can see Ansel’s barely-sublimated frustration in the scene where he stiffs Claire’s folks with the check for lunch. He quickly slicks over the corners of his mustache with this thumb and fore-finger. Then he bullishly charges through an awkward silence, and presents his new clients with their bill: “Thank you for paying.”

Orser’s performance is strong, but it’s not really the spine of Stearns’s film. Think of Ansel as a disoriented compass, someone that tries to steer Claire towards freedom, but repeatedly loses his bearings. “Faults” is, in that sense, all about atmosphere. Stearns’s discerning eye for visual composition is remarkable. He has a clear love of texture, and draws viewers in by calling attention to the whorls on cheap plywood walls, or the contrast of red blood on a white-and-blue tile floor. He’s not obsessed with visual symmetry, but each shot feels composed without being ostentatious, or over-determined.

That style is crucial to the film’s success. “Faults” only works if you believe that Ansel’s not in control, and not in a wacky underdog-messes-up-but-inevitably-does-right kind of way. You have to really feel like the film could suddenly be about Claire’s parents, or the two guys Ansel hires to abduct Claire, or the beguiling debt-collector (Lance Reddick) that Ansel’s agent pays to harass Ansel. You’ll know that Stearns achieves this feeling in a scene that–without spoiling anything–suggests a terrifying wrinkle to Claire’s relationship with her her loved ones that may or may not just be a dream. In this scene, all of the information you need is suggested out-of-focus in the background of the camera frame’s. It’s a seriously unnerving scene, one that hints at possible future revelations without decisively steering viewers towards a sense of closure. “Faults” ultimately doesn’t go anywhere you don’t expect it to, but it’s so immediately engrossing that you won’t care.