Near the end of the gentle, affecting film that bears her name, Fatima (played by newcomer Soria Zeroual) reads a bit of poetry she’s composed to her oldest daughter, Nesrine—in Arabic, because she’s still learning French. The poem is about her life, about facing the world alone with her daughters. “This is my intifada,” she says: her act of uprising. Raising her daughters is her rebellion against oppression.

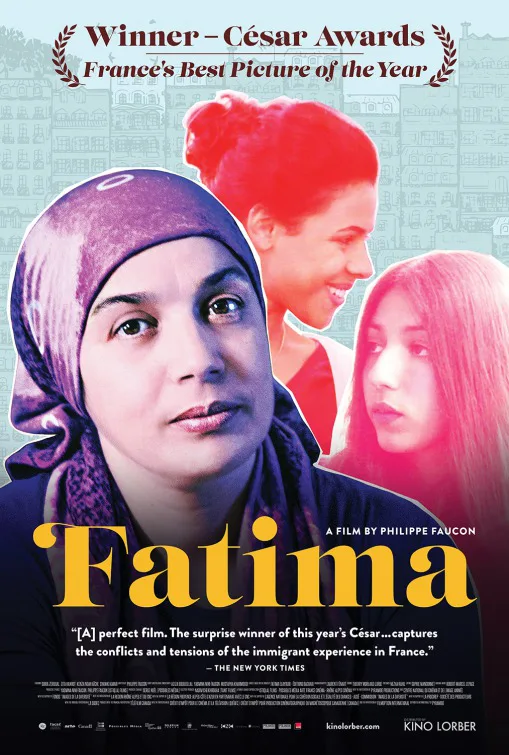

“Fatima” is a modest but engrossing movie, clocking in at a slim 78 minutes, that explores what that sort of act of rebellion might look like for a woman like Fatima: a North African immigrant in her mid-forties, divorced, living in Lyon, in a community that doesn’t seem overly eager to assimilate her or women like her. As such, it combines several currents running through contemporary European cinema: the sticky matter of immigration and assimilation, the challenges faced by the working class, and the tricky matters women navigate when they’re members of both of those groups. Fatima works as a cleaner, tries to learn to read and write French beyond a basic level, and raises her two daughters. Nesrine (Zita Hanrot), her eldest, is a first-year medical student far more mature than her 18 years; Souad (Kenza Noah Aïche), on the other hand, is 15, surly and disdainful of her mother’s job and her broken French. All of them face pressure from the immigrant community, who sees Nesrine as stuck-up and Souad as a reflection on Fatima.

The film—which screened in Director’s Fortnight at Cannes in 2015—mostly sticks to the women’s stories, though the girls’ father (Chawki Amari) is still in touch with their lives. Fatima brings food to Nesrine and encourages her to study hard, but also to make room in her life for love. Nesrine stretches herself to the breaking point with her studies. Souad plays hooky and fights with her mother.

Fatima’s poetry and reflections from her diary, quoted throughout the film, come from a collection of writing by Fatima Elayoubi, a North African immigrant woman with a similar life to her on-screen counterpart. In some films, a device like this comes off as heavy-handed (watching people write is about the dullest thing that happens in movies); here, though, it’s something much more moving. Fatima is not much for complaining, and she’s convinced of her own worth, even as Souad slings insults at her and her work. But she is sensitive about her relative illiteracy in French. It’s a marker of her otherness not just from the French culture, but from her own daughters, who speak the language fluently and help her sort out confusing turns of phrase, with middling success. So Fatima’s ability to express herself in language is important, and is another way of pushing back on a culture that wants to mark her as part of an uneducated underclass.

And in some ways, though “Fatima” is a simple, but strongly drawn story of three immigrant women from two generations struggling to sort out their place in contemporary French society, it also boasts streaks of more universal feminism. The women don’t go around talking about “having it all,” because they’re working hard to have anything at all—particularly Nesrine, who is terrified to fail in school mostly because she couldn’t face seeing her parents’ hopes dashed. But as a woman who wears a veil, raises daughters, and works very long hours while trying to learn the language and culture of the people around her, Fatima’s statement about intifada is revealing. For her, the goal isn’t to be French, but to resist the expectations she feels from other women like her and carve out her own path. Raising her daughters, on her own, to be successful women who nonetheless do not forget their roots—while not insisting they conform to the expectations of others—is her way of exercising her agency.

Director Philippe Faucon (“The Disintegration”) was born in Morocco and raised between Morocco and Algeria before emigrating to his father’s native France, and his observation of the three women is both intimate—we watch Fatima wash couscous, tie her headscarf, write in her diary, and fight with Souad—and entirely without pity. Which is of course as Fatima would have it. She is not sorry for herself, and the movie doesn’t ask us to be, either. It’s sometimes funny, but always empathetic, and Faucon wisely leaves many of the most dramatic moments off-screen, focusing our attention on how the circumstances and the aftermath affect the women’s relationships with one another.

At the end of the film, celebrating one of her daughters’ successes, we watch Fatima as she slowly reads a list of results posted on the wall. Her smile grows as she registers the details, and in that moment, it’s clear: her daughter’s success is a sign that her own act of uprising is working.