Peering into obscure corners of Paris, Jean-Jacques Beineix emerged with an assembly of unlikely, even impossible, characters to populate his “Diva” (1981), a thriller that is more about how it looks than what happens in it. Here is an exhilarating film made for no better purpose than to surprise and fascinate. I remember it at Toronto 1981, where it arrived unknown and unsung and won, as I recall, the festival’s first audience award. Now released in a restored print, it glistens in its original magnificence.

The plot is both preposterous and delightful, put together out of elements that seem chosen for their audacity. The central character is a young postman named Jules (Frederic Andrei), who races the streets on his moped, delivering special delivery mail and pausing at an opera recital to secretly record a performance by a tall, black, gorgeous American soprano named Cynthia Hawkins (Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez). He has a professional-quality Nagra recorder hidden in his bag. After the performance, he enters her dressing room with a crowd of well-wishers and steals her elegant white silk gown.

Hawkins is famous for never having entered a recording studio, and we later learn she has never heard her own voice. Now Jules has the only existing tape of her singing; it is priceless, but he wants it only for himself. Unfortunately, he was seen making the recording by two Taiwanese bootleggers, who want to steal it from him. And his problems grow more complex when two gangsters murder a prostitute on a street where he is making a delivery. She has a tape incriminating the chief of police in a sex-slavery ring, and before she dies, she slips the tape into the carrier bag of his moped. Now four deadly crooks are looking for him.

Jules lives in his own way, in his own shadowy industrial space, which is filled with crashed cars and wall paintings of automobiles. Here he listens to the sublime voice. (Fernandez, an established opera diva, did her own singing and created an early-1980s boom for Catalani’s opera “La Wally” and its first-act aria.) One day at a record store, Jules spots a Vietnamese nymphet named Alba (Thuy An Luu) shoplifting a 33 rpm record with a cleverly designed art portfolio, which seems to contain only nude photographs of herself.

He follows her, asks her how she did it, they discover they share a love of opera, and he lets her listen to his recording. She supplies it to a mysterious, cigar-smoking, handsome older man named Gorodish (Richard Bohringer), who lives in an industrial loft of vast size, furnished mostly by a chair, a bed, a bathtub and an aquarium. Is this man her lover? Her guru? Why does he seem to possess unlimited wealth and power?

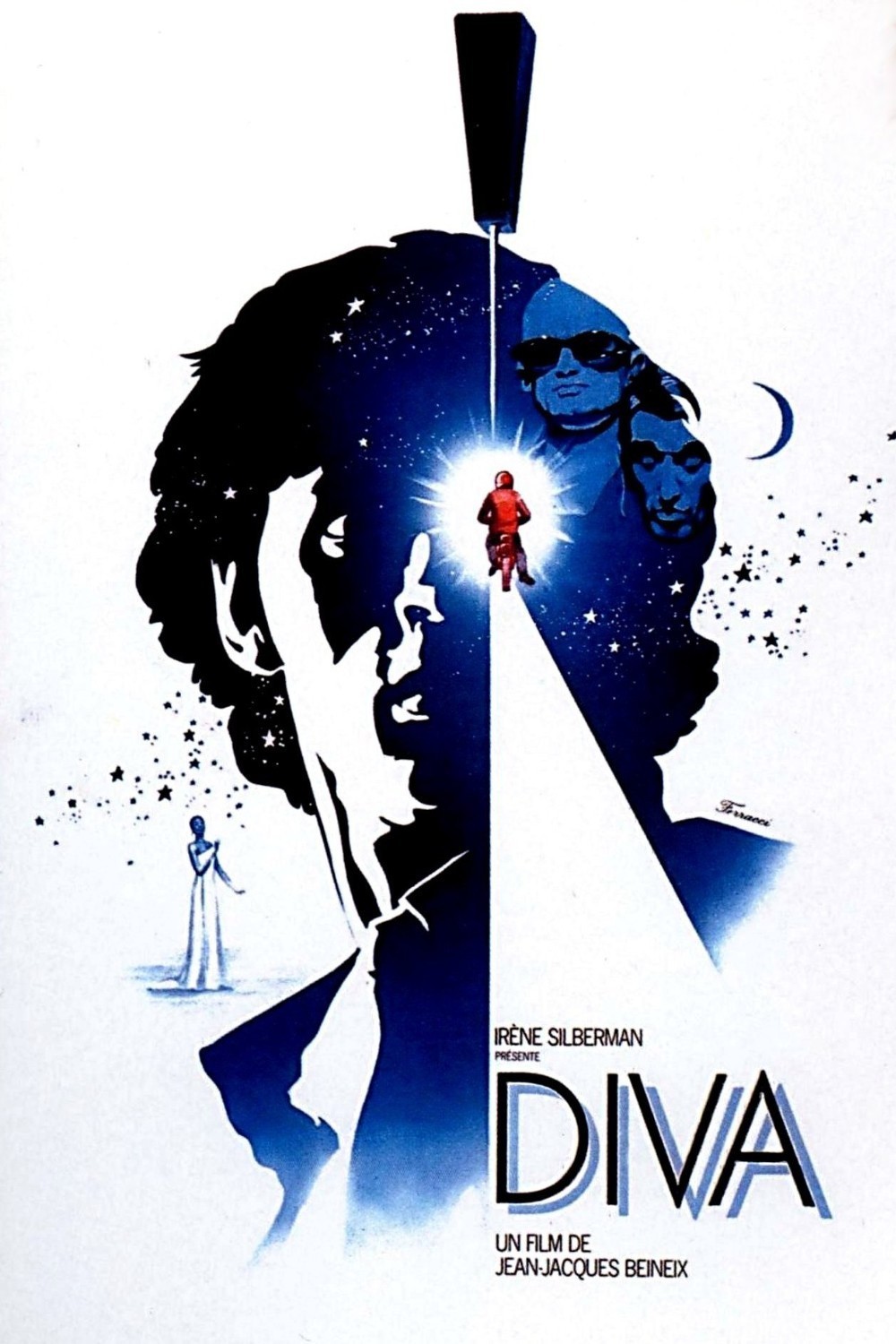

Now all the pieces are in place, and what remains is only for the film to spin them in a dazzling kaleidoscope of sex, action and startling images. “Diva” has been referred to as the first French film in the post-New Wave cinema du look, defined by Wikipedia as a group of films “that had a slick visual style and a focus on young, alienated characters that were said to represent the marginalized youth of Francois Mitterrand’s France.” It was the look itself, rather than the content, that defined the films, and sometimes the plots seemed almost designed to create photographic opportunities.

The films were drawn to untamed non-bourgeois spaces such as industrial wastelands and the Paris Metro rather than tidy indoor spaces. “Subway,” a famous 1985 cinema du look by Luc Besson, has a crime plot that takes place largely in the Metro, where a rock concert is even staged. And in “Diva,” the most sensational sequence involves Jules being pursued by the cops and actually racing his moped down the Metro stairs, onto a train, off again and up another flight of stairs. The photography of this shot helps explain why Philippe Rousselot won the Cesar, or French Oscar, for his cinematography (the film won three more Cesars, for best first work, best music and best sound).

Not the least of the film’s attractions is the unexpected casting. You could say many characters were typecast, but they were largely unknown at the time of the film’s release. This was Andrei’s first significant role, for example, Fernandez’s first and only film, and the first feature of Dominique Pinon, called “Le cure,” (“the treatment”). A short young man hiding behind mirrored glasses, an earplug always in his ear, his head shaved, he performs his treatments with a heavy awl, which he throws into the backs of his victims, killing them. He likes to pose with the point of the awl tickling his chin. He doesn’t smile.

The presence of Fernandez is awesome; the filmmakers discovered her at a performance of “Carmen” in Paris and found her sufficiently awesome to justify the young postman’s obsession with her. The moments when he returns her gown, and then the tape, are handled by her with a subtle balance of astonishment and amusement.

The most mysterious characters in the film are, of course, the rich recluse Gorodish and his bold young friend Alba (this was the first of five films made by Thuy An Luu). The characters are found in a series of popular French thrillers by Delacorta, including Diva, where we can learn that he is a musician, she is a 14-year-old wise beyond her years, their relationship is unconsummated, and she has a knack for bringing trouble home for him to solve, just as a cat will bring home a mouse, and just as she brings Jules to his lair. In a sense, you could say that Delacorta (real name Daniel Odier) was a co-inventor of the cinema du look, since his prose emphasizes slick surfaces, neon colors, unorthodox settings and characters from the shadows.

Here is an idea of his prose, from his 1990 novel Alba: “… he noticed on the white table a piece of paper adorned with Alba’s lovely handwriting. Her practice of the Tao mysteries had made it as deliciously fluid as one of her inspired kisses, the one she called a dawn ottoman.”

One peculiarity of the plot is that Beineix withholds much from the characters, but almost nothing from the audience. We know what both sides know, and the result is to focus our attention on the how rather than the why. The film is an “exercise in style,” yes, but that need not be a criticism. We go to different films for different reasons, and “Diva” gives us such a sensuous flow of images that we enjoy the characters moving through them. Rousselot’s camera itself sometimes seems governed by the images, rather than controlling hem.

As the critic David Edelstein observes, “when the bicycle-messenger hero listens to Wilhelmenia Fernandez sing the aria from ‘La Wally’ … at that first sublime high note, the camera lifts off and begins to sway. Every time the aria is replayed, the camera moves at the same instant. It has to. This is style as a force of nature.”

For Beineix (born 1946), “Diva” was a sensational start to what turned out to be a rather anticlimactic career. In 1984, he was back at Cannes with “The Moon in the Gutter,” which was booed, perhaps for its over-insistence on style; some shots were so elaborate or obviously concocted that they upstaged and even obscured their content. In 1986, he made the sensational “Betty Blue,” which became a huge success in France and still plays as a cult film, primarily, I am convinced, because of its generous nudity. Interestingly, in 1997 for the BBC, he made “Locked-in Syndrome,” a documentary about Jean Dominique Bauby (the subject of “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly“).