“Clean, Shaven” is an attempt to enter completely into the schizophrenic mind of a young man who is desperately trying to live in the world, on whatever terms will “work” in his condition. It is a harrowing, exhausting, painful film, and a very good one – a film that will not appeal to most filmgoers, but will be valued by anyone with a serious interest in schizophrenia or, for that matter, in film.

I was on a program the other day with Tom Wolfe, the author and social critic, who was defending novels as the only medium that truly allows us to enter into another person’s point of view. We can go inside the heads of written characters, he said, in a way that doesn’t work with movies or the theater. In many cases he may be right, because movies more often encourage us to be voyeurs than to identify with characters. But a film like “Clean, Shaven” is a shattering exception to his rule, since it restricts itself almost entirely to the way a person with schizophrenia must negotiate the horrors of everyday life.

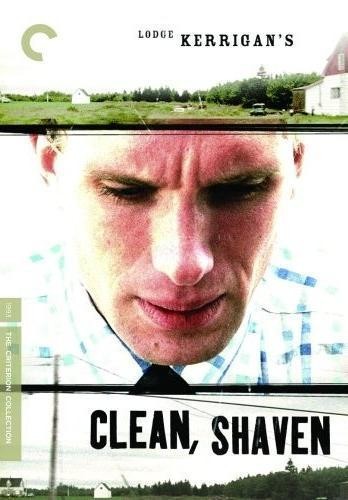

The movie is about Peter Winter (Peter Greene), who has a car but apparently no home, and has perhaps recently been released from treatment, although that is left vague. He wants to make a trip to see his daughter, from a marriage made before his condition developed. We follow every step of his excruciating journey, in a performance by Greene of great power and nerve.

There are terrors we can hardly imagine; he breaks out the glass of some of the car widows, and fills in the holes with taped newspapers. He wraps the rear-view mirrors of the car with paper.

Driven by some deep need, he tries to cut his hair and shave, and both operations produce painful cuts to which he seems oblivious.

The movie’s sound track is sometimes harsh and obtrusive: We hear voices, some from the radio, some from inside his head or his memories. Power lines seem to emanate a low buzzing presence. The sound track is entirely subjective; in a restaurant, his head is filled with noise until the moment when he begins to put a lot of sugar into his coffee, and then there is complete silence, as if his absorption in the task has quieted the sounds for a moment.

There are a few quiet scenes outside his presence. We meet his mother, who calls his ex-wife and tells her, “Peter’s back.” He stops at his mother’s house, and she expresses concern for him, but we can see at once she has a long, exhausting history of dealing with his condition. She gives him the makings of a sandwich, and he constructs it with the care a child might lavish on building blocks.

Eventually he does confront his young daughter.

What suffuses every moment of the movie is the constant agony he is in, because of the way his condition causes the everyday world or sensations to assault him. There is a gruesome moment when he cuts a fingernail loose from his finger (many viewers will close their eyes), as if the pain will for a moment free him from the greater pain of being alive.

The movie is, more than anything else, an uncompromising experiment in creating, for the viewer, an idea of what schizophrenia is like. The writer and director, Lodge H. Kerrigan, has made a leap of imagination that is both courageous and empathetic: He doesn’t see Peter from the outside, as a danger or a threat, but from the inside, as a suffering man who still retains those instincts that make us human, including love for our children.

That society cannot see him with the same empathy is perhaps inevitable. Peter is the kind of man we quickly cross the street to avoid. Now we understand how much he needs to avoid us, as well.