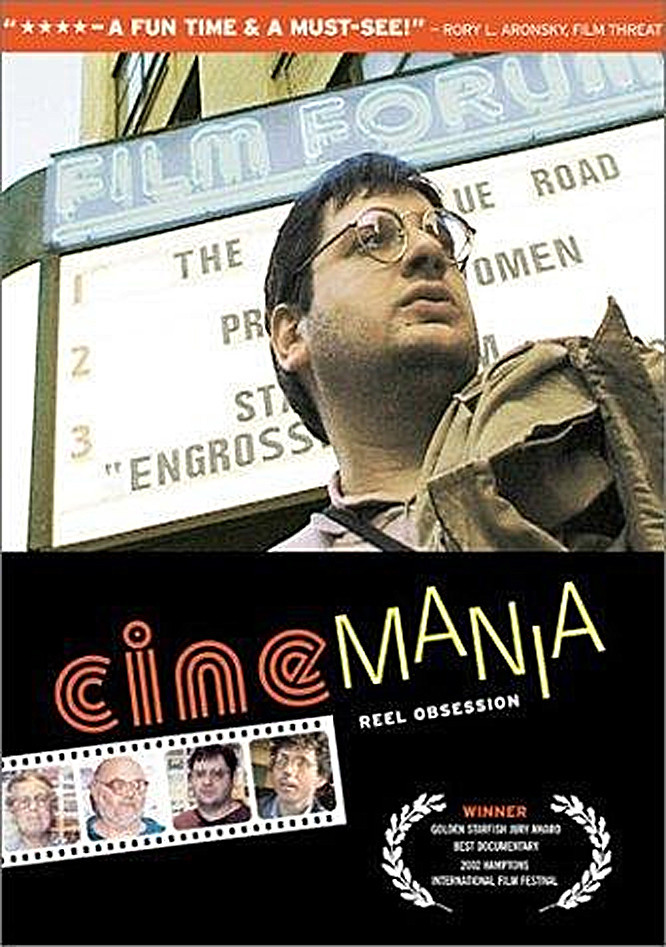

“Cinemania” tells the story of five New Yorkers who spend as much of their life as possible going to the movies. They go to a whole lot of movies. It’s my job to attend movies and in a year I probably see only about 450. If I were one of these cinephiles, I would have seen 700 to 1,000, would know the exact count, and would also have the programs, ticket stubs, press kits and promotional coffee mugs.

These are not crazy people. Maladjusted and obsessed, yes, but who’s to say what normal is? I think it makes more sense to see movies all day than to golf, play video games or gamble. Not everyone agrees. I know people like these, and I understand their desire to be absorbed in the darkness and fantasy. As a professional moviegoer, my life is even a little nuttier than theirs, because they at least choose which titles to see, and spend a lot of time seeing revivals and classics; I have to monitor whatever is opening every week.

The five cinephiles are Jack Angstreich, Eric Chadbourne, Harvey Schwartz, Roberta Hill and Bill Heidbreder. They agree that New York ranks with Paris as the best place to see a lot of movies. They have the screening times and subway schedules coordinated to maximize the number of movies they can see in a day, and Jack deliberately eats a constipating diet (no fruits or vegetables) to minimize trips to the restroom. None of them are married (duh), and some talk about their nonexistent sex lives. Bill says he wouldn’t want to make love with Rita Hayworth, because he couldn’t do it in black and white, and her dark lips in old b&w movies are crucial to her appeal. Bill was disappointed, too, during a trip to Europe. He loves French movies about people sitting in cafes, but when he went to Paris and sat in a cafe, he discovered it was–only a cafe. Not as good as in the movies.

They have their specialties. Bill likes European movies since the French New Wave. Harvey obsesses on running times. Eric will go to see almost anything, including “The Amazing Crab Monster.” Roberta gets in fights with ushers who impede her single-minded determination to see movies. Jack wants to get a cell phone so he can call the booth and complain about the projection without having to walk out to the lobby. For key screenings, they arrive early and save their favorite seats, and they are willing to take direct measures against anyone interfering with their enjoyment of a movie.

They really, really like movies. They cry during them. One stumbled out of “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” and walked for blocks in the rain, weeping. “A commitment to cinema means one must have a technically deviant lifestyle,” Jack acknowledges. That includes being able to avoid the tiresome necessity of earning a living. Jack has inheritance (“If I don’t blow it all on hookers, I will never have to work”). Bill is on unemployment. Harvey, Eric and Roberta are on disability, and at one point discuss the possibility that having to go to the movies should qualify them for disability.

They talk warmly and with enthusiasm about certain titles, but I have the eerie feeling that they must be at a movie whether they enjoy it or not. And only a real movie will do. Except for Eric, who also watches a lot of videos, they insist on movies and hate TV. Sometimes their dreams are movies, they say, perhaps in black and white or CinemaScope. But only the nightmares are in video. Or is it that anything on video is a nightmare? To be asleep at all is to lose moviegoing time. “I’m so far behind in the cinema,” Jack sighs, “that it’s just a hopeless Sisyphean struggle.” As the movie ends, Jack and the other four subjects have gathered to watch another movie: this one.