Greed, for lack of a better word, is perhaps not as good as it used to be. It’s ugly and treacherous, and unabashedly so, in “Capital,” a financial thriller set in the highest echelons of France’s wealthy and powerful.

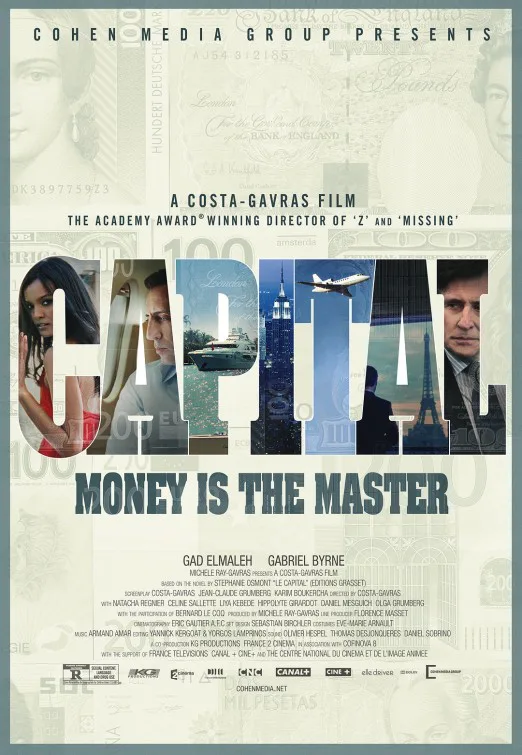

Veteran director Costa-Gavras, who made his name decades ago with films that sharply addressed political issues—most notably, “Z” and “Missing“—focuses his attention this time on the kind of unscrupulous, unchecked money grab that caused the 2008 economic collapse. Like “Arbitrage” and “Margin Call,” which depicted that cataclysmic moment in our recent history, “Capital” features men behaving badly but with only a few glimmers of panic. His film remains suspenseful and his hero—or rather, his anti-hero—remains remorseless.

As Marc Tourneuil, the young and newly minted CEO of one of Europe’s largest financial institutions, Moroccan actor Gad Elmaleh rarely flinches and barely breaks a sweat. He’s cold and calculating and—in case the extent of his cynicism weren’t already clear—he often breaks the fourth wall to share his candid thoughts.

Elmaleh has a mesmerizing way about him, though; he’s primarily a stand-up comedian—the Jerry Seinfeld of France, if you will—but he’s just chilling in this much more dramatic role. The fact that his character is so aware about his own schemes and selfishness strangely makes us want to root for him to get away with it all. (Richard Gere was similarly charming in his sliminess in “Arbitrage.”)

Marc, an up-and-coming executive at the fictional, Paris-based Phenix Bank, finds himself ascending to its highest rank when his boss suddenly collapses on the golf course. Board members have chosen him for the position because they view him as a pawn—someone inexperienced and malleable who will serve as a placeholder until they can find the “right” chief executive officer. But Marc recognizes that they underestimate him and makes the most of his opportunity. He doesn’t want the respect of these men. He wants money—which will bring respect.

Unsurprisingly, everyone else wants something from Marc. Here’s where some of the characters and motivations get a little fuzzy in the script from Costa-Gavras, Jean-Claude Rumberg and Karim Boukercha, based on the novel by Stephane Osmont. Some people want to control him, like Gabriel Byrne’s ferocious and foul-mouthed hedge-fund manager, who lures him to Miami with a yacht full of bikini-clad babes. (“The fauna,” as he amusingly refers to them.) Then there’s the hard-partying and seemingly ubiquitous supermodel Nassim (Liya Kebede), who wants to get close to him, only to push him away.

Their “relationship,” such as it is, ends horrifically in a way that’s hard for us to get a handle on as viewers. (This isn’t exactly a spoiler—their mutual attraction is dangerous from the start.) Costa-Gavras never judges this complicated character, but it’s also difficult at times to grasp the director’s intentions. There’s also an intriguing executive in the London office (Celine Sallette) who’s an expert on Japanese banking; his interest in her remains frustratingly ambiguous.

Oh yes, Marc also has a wife (Natacha Regnier), who comes from old money herself, and a son who barely matter to him and rarely appear on his schedule. Marc’s wife seems admirably down-to-earth, as evidenced by her rejection of a $22,000 Dior gown sent especially for her to wear to a black-tie gala: “I don’t want to have to dress like a CEO’s wife,” she argues. But such expressions of honesty have no place in this world.

To the rank and file, Marc seems like an innovator when he offers them the opportunity to complain away about their bosses and colleagues through a confidential self-assessment. (At the global videoconference where he introduces these surveys, Costa-Gavras presents the striking image of hundreds of employees clapping wildly in tiny boxes on a giant screen.) But managers and longtime executives hate the plan, which results in thousands of layoffs—and sends the bank’s stock skyrocketing.

Still, a massive takeover is underway, and Marc must figure out a way to navigate it rather than becoming its victim. Having a strong handle on the workings of complex global finance probably helps while watching “Capital,” but isn’t a necessity; Marc spells things out pretty plainly when he glibly describes himself as a Robin Hood to the rich. The film could take place in any number of settings where ego and testosterone dictate action and fortunes are won in lost in a matter of minutes.

The famously left-leaning Costa-Gavras is preaching to the choir in his indignation, but he does so in slick, brisk fashion.