The second feature written and directed by the prodigiously talented Irishman John Michael McDonagh opens with a quote from Saint Augustine: “Despair not, one of the thieves was spared; presume not, one of the thieves was not.” (It is no accident that this bit of wisdom is cited in “Waiting For Godot,” an obscure theatrical work by another talented Irishman name of Beckett.) Later in the movie, Fiona (Kelly Reilly) the daughter of County Sligo priest James Lavelle (Brendan Gleeson)—Lavelle took the vows after his wife, Fiona’s mother, died years earlier—takes confession with her literal and spiritual father, and, obliquely addressing the troubles that informed her recent, half-hearted suicide attempt, asserts, “I belong to myself, not to anyone else.” To which Father James responds, “True. False.”

A mordant sense of duality that eventually takes on near-apocalyptic dimensions runs through this very darkly comic tale, telling a week in the life of Father James. Sunday kicks off pretty horribly. A man ostensibly offering Father James his confession explicitly describes his sexual abuse at the hands of the priest years earlier, and outline his plan for revenge: he intends to kill a “good priest” in exactly a week. He means for that good priest to be Father James, and invites him to a beach spot to meet his doom.

This disturbs James, as well it might. But he does not go to the authorities. Instead, he tends to his flock, such as it is. And a more perverse bunch would be hard to find anywhere else than in a provincial, lonely Irish remote. There’s the local butcher (Chris O’Dowd), who might well be slapping around his sexpot wife (Oria O’Rourke), who’s brazenly conducting an affair with an African immigrant auto mechanic (Isaach de Bankole). The local barkeep’s a ball of resentment, the town’s most dapper young man is completely socially inept, the police chief’s a glib sourpuss who makes no attempt to disguise the fact that he does business with a manic, Jimmy-Cagney-impersonating male prostitute. The local hospital biggie is a monstrously cynical atheist with a monstrous anecdote to explain his poor attitude. The local fat cat is swilling in his ale, and worse, at his manse after being abandoned by his wife and child. And so on. It is again no accident that the only characters who are at all kind to Father James, besides his daughter, are non-Irish ones: a very aged American ex-pat author (M. Emmett Walsh, whose presence is extremely welcome despite his looking like death warmed over, which admittedly works for the character), determined to off himself before he goes completely decrepit, and a French widow (Marie Josée Croze) who commiserates with Father James after he performs last rites on her husband.

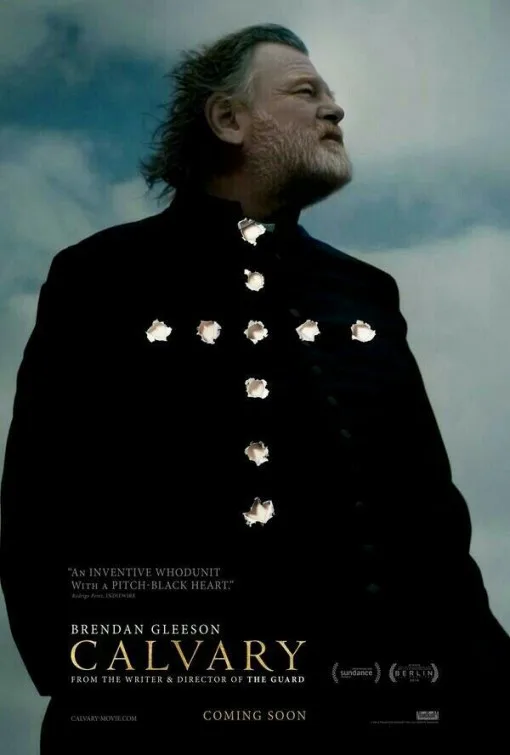

McDonagh’s structuring is unusual: almost all the scenes are what are referred to in the theater as “two handers,” that is, exchanges between only two characters. Each scene tackles a particular variation on the movie’s theme, which is the earning of forgiveness, and whether taking what’s said to be the right action is sufficient to do so. Gleeson’s performance is magnificent; sharp, compassionate, bemused, never not intellectually active. McDonagh’s dialogue is similarly never not sharp, and only occasionally lost to an actor’s Irish accent. As the picture progresses, Father James’ parishioners morph from a group of perverse individuals to one of intransigently spiteful lunatics. McDonagh takes considerable risks, in this day and age, crafting what’s essentially an absurdist allegory. By the film’s finale, this viewer felt that one or two of the risks didn’t entirely pay off, but my admiration for McDonagh’s brass remained intact. This is the kind of movie that galvanizes and discomfits while it’s on screen, and is terrific fodder for conversation long after its credits roll. Even if you are neither Catholic nor Irish, this “Calvary” will in no way be a useless sacrifice of your moviegoing time.