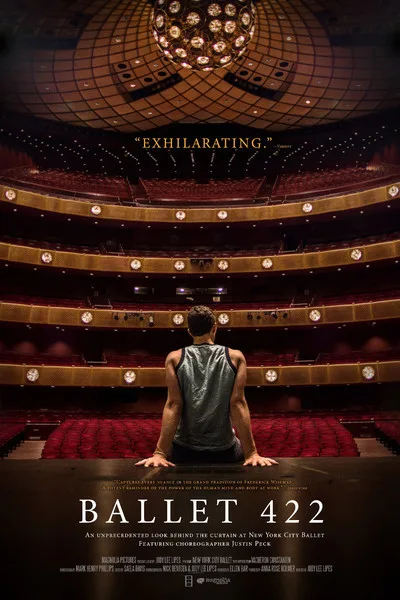

Art isn’t easy. That’s the main “takeaway” from this brisk and engaging documentary, directed by Jody Lee Lipes. After a few text notes explaining who the main players are—they are the New York City Ballet and a dancer/choreographer named Justin Peck—“Ballet 422” chronicles the creation of the four-hundred-and-twenty-second original ballet mounted by the company, from its conception to opening night.

As in the films of documentarians David and Albert Maysles and Frederick Wiseman, this true-life chronicle eschews both narration and on-camera interview. Justin Peck does not explain the premise of his ballet, his reason for choosing the music (“Sinfonietta La Jolla” by 20th-century composer Bohuslav Martinu), or any such thing; instead, Lipes’ cameras show him thinking and working in an empty rehearsal room with a boom box, or in his quiet walk-up apartment. Soon he’s laying out moves for his lead dancers, conferring with the costume designers, lighting directors, the orchestra conductors, and so on.

The process as chronicled by Lipes is relatively drama-free but extremely labor intensive. Nobody’s a diva, voices are never raised, there’s no last-minute crisis. Which isn’t to say there isn’t tension, or irony, or interest. Part of the magic of the dance, if you’re a fan of it (it’s not really my cup of tea, but you can’t like EVERYTHING), is the illusion that the work you’re watching has just been conjured out of thin air, and all of the members of the team creating Peck’s ballet are master illusionists. But they’re also people with jobs, and the movie does an excellent job of showing the commonplace workaday atmosphere that is, in fact, a big part of that business we call show.

Peck is quiet, conscientious, dedicated, and well-mannered, which is in pretty stark contrast to Brock Enright, the subject of Lipes’ 2009 film “Good Times Will Never Be The Same,” which depicted Enright generally being the worst person in the world, and ended with the nightmare vision of his actually spawning. But Lipes also depicted Enright as a guy with a work ethic. So there IS a thematic throughline here, auteurists. The irony of Peck’s position is, while he’s on the rise as a choreographer, as a dancer he’s in a rather more plebian position, which provides the movie with a punchline that Lipes neither overstates nor shrugs off. The movie, which sticks to a relatively rough-and-ready handheld visual style for the most part (Lipes’ is largely known for his work as a cinematographer; he’s collaborated closely with Lena Dunham and shot Judd Apatow’s upcoming “Trainwreck”), ends on a very beautiful and still shot of the site of the City Ballet that will remind New York-based viewers of their cultural privilege, and maybe goad them into taking advantage of it more often. Heck, I was thinking maybe of checking out a ballet, even.