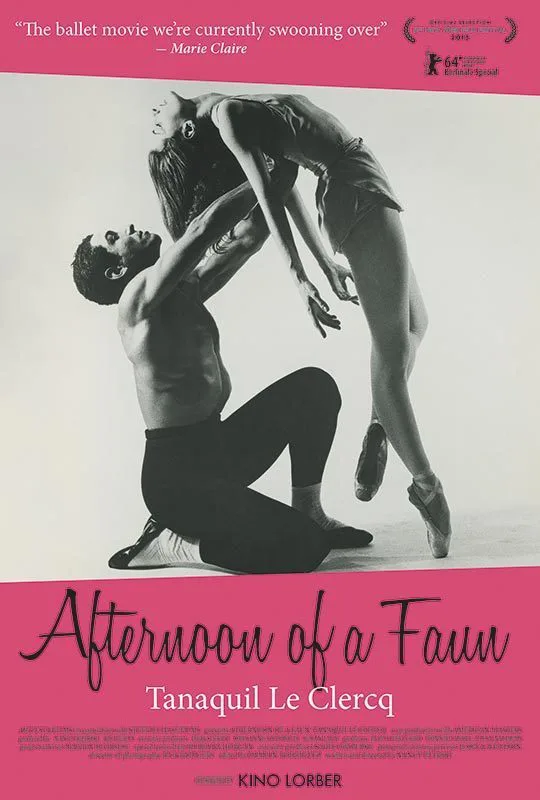

Many documentaries about ballet and its practitioners, even the very best, understandably appeal mainly to a core audience of dance aficionados. Nancy Buirski‘s mesmerizing, beautifully crafted “Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil le Clercq” proves a striking exception to that rule. While it does profile the work of brilliant dancer, the film also contains two complex and moving love stories as well an account of a physically devastating tragedy followed by an extraordinary tale of struggle and survival.

Tanaquil le Clercq was a muse and love interest of two of the last century’s greatest American choreographers, George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. Born in Paris in 1929 and raised in privileged, sheltered circumstances in New York, Tanny, as her friends called her, started studying dance as a child and was at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet when he discovered her. Though she was only 15, he cast her in lead roles and she quickly became a star, having never served in the corps de ballet.

Her skill as a dancer is evident in the clips director Nancy Buirski provides, but le Clercq was also helped, clearly, by her looks. Tall, svelte and long-legged at a time when most ballerinas were short, she exuded a coltish energy and cut a striking figure on stage. Her face also had a distinctive allure, a mixture of simplicity and understated ethereality, like a more angular Julie Harris with a bit of Lauren Bacall’s youthful insouciance.

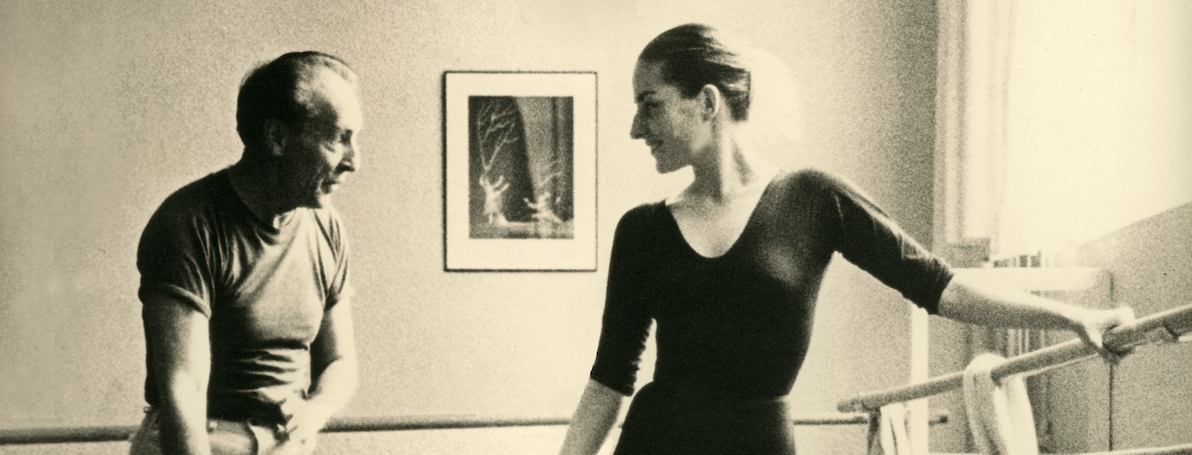

Already middle-aged when he met her, the Russian-born Balanchine had a history of depending creatively and emotionally on his prima ballerinas. He had married four of them before he met Tanny, and all had eventually left him (rather than the other way around) when it seemed their artistic partnership had run its course. With Tanny, the pattern repeated, but from the testimony of those who knew them, the love on both sides was profound. They married in 1952.

Robbins, a bit older than Tanny, was infatuated with her from the time they met, and said she was the reason he decided to the join the New York City Ballet and work under Balanchine. Some of the most moving parts of the film are excerpts from letters between Jerry and Tanny (read by actors) that bespeak a complex mix of friendship and romantic feeling, one that was destined to leave him both enthralled and frustrated. He apparently was crushed when she married Balanchine.

In 1956, the company went off on a European tour at a time when the specter of polio was terrorizing much of the world. While most of the dancers took the newly invented Salk vaccine before they left, Tanny decided at the last minute not to. She was stricken in Copenhagen and put in an iron lung with expectations that she would not survive. She did pull through, but would never walk, much less dance, again.

The sudden horror of the dancer’s illness and her struggle in its aftermath are where the film’s fascinating chronicle of a talented artist’s ascent turns even more absorbing. In a strange way, it seems that though Tanny’s emotions are roiled by her drastic change of fortunes, her spirit is largely unchanged, and perhaps even strengthened. In any case, Balanchine remains an ardent support through her treatment in Warm Springs, GA, and return to New York. And while she complains that Robbins is an erratic correspondent, his letters and photos of her make it clear that his attachment to her is as strong as ever.

Those photos make the point that, where some documentaries need a copious amount of material on their subjects, others manage to turn a paucity of sources into an advantage. Here, there were only a couple of Tanny interviews during her career for Buirski to draw on, and none following her illness (le Clercq died in 2000), and the archival footage of her dancing of course came well before the era of HD and snazzy production values.

But precisely these limitations help draw the viewer even more deeply into Buirski’s portrait of the dancer. Watching Tanny’s luminous countenance in Robbins’ expressive photos or the post-polio Super-8 movies made by friends, one senses a truly amazing spirit blessed with an insight, a warmth and a generosity that were far beyond the normal. As one of her intimates says, “her regard was all acceptance, forgiveness.”

Ultimately, a great film about a single person touches upon the mystery of human personality, and “Afternoon of a Faun” does that with uncommon grace. While some viewers are sure to come away from the film wishing they had seen Tanny dance, perhaps even more would wish they had been able to spend an afternoon in the park with her.

It should be noted that Buirski and editor Damian Rodriguez have done a superb job of telling their story through interviews and footage of dances that, though old, remain striking. The most hypnotic of all, which opens and closes the film, is from the eponymous “Afternoon of a Faun” piece that Robbins created for Tanny and Jacques d’Amboise. In an old black and white kinescope, the dancers perform as in a studio, but with the camera where the mirror should be. Somehow the effect is spell-binding even decades later, proof of the magic that two figures on a bare stage can create.