“You people!” says Eliot Deacon sadly, and with a touch of frustration. He is referring to the dead. They are whiners. They’re not ready to die, they’ve got unfinished business, there are things they still desire, the death certificate is mistaken, and on and on and on. Deacon, as a mortician, has to put up with this.

Take Anna as an example. She drove away from a disastrous dinner with her boyfriend, was speeding on a rainy night, and was killed in a crash. Now here she is on a porcelain slab in his prep room, telling him there’s been some mistake. Deacon tries to reason with her. He even shows her the coroner’s signature on the death certificate. But no. She’s alive, as he can clearly see. Besides, if he’s so sure she’s dead, why does he carefully lock the door from the outside whenever he leaves the room?

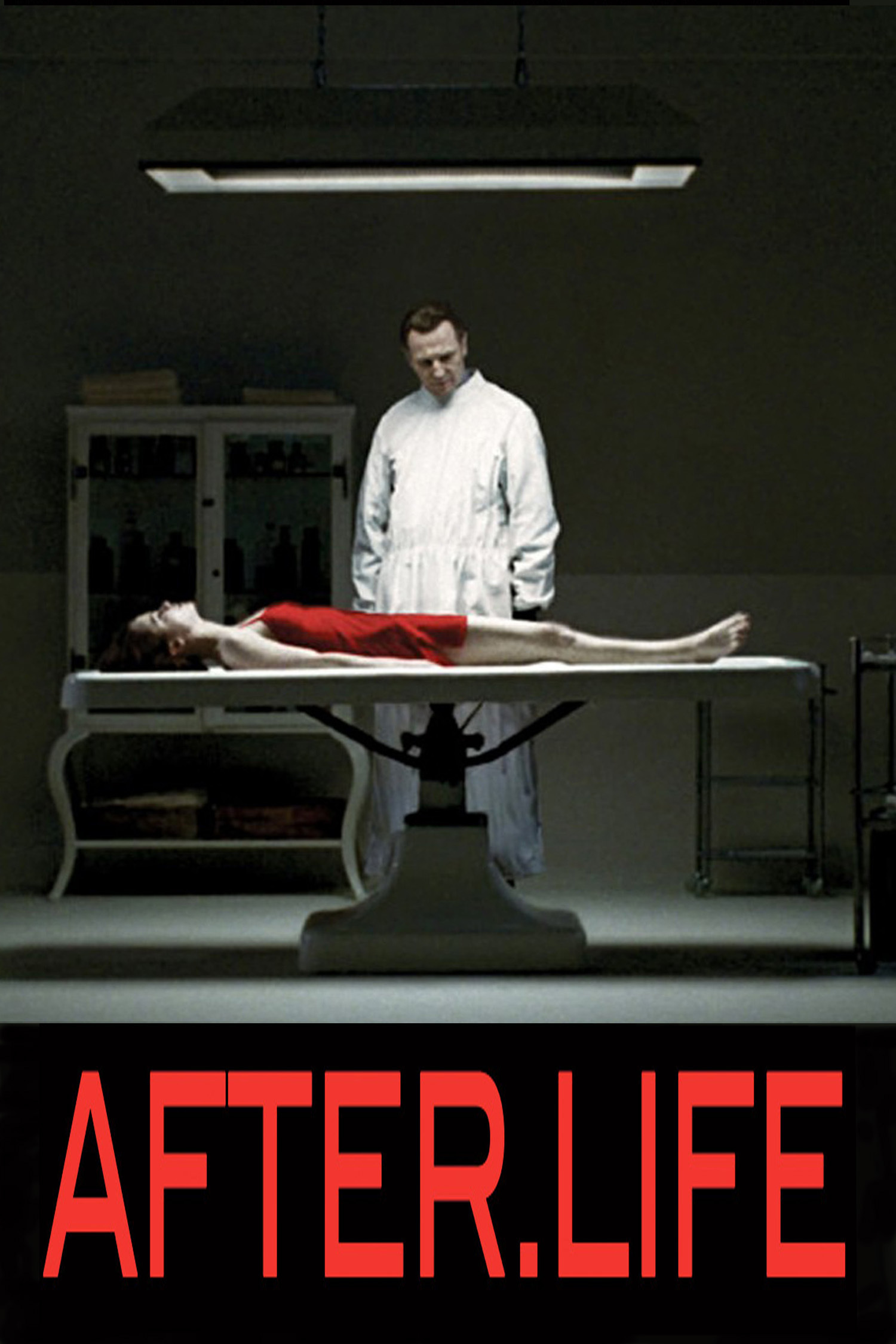

“After.Life” is a strange movie that never clearly declares whether Anna (Christina Ricci) is dead or alive. Well, not alive in the traditional sense, but alive in a sort of middle state between life and death. Her body is presumably dead. She has no pulse, and we assume her blood has been replaced by embalming fluid. Yet she protests, argues, can sit up and move around. Is Deacon (Liam Neeson) the only one who can see this? Maybe he’s fantasizing? No, the little boy Jack (Chandler Canterbury) sees her too, through a window.

Jack tells her boyfriend Paul (Justin Long). He believes it. He’s had a great deal of difficulty accepting her death. He still has the engagement ring he planned to offer her on that fateful night. He tries to break into the funeral home. He causes a scene at the police station. He sounds like a madman to them.

“After.Life” is a horror film involving the familiar theme of being alive when the world thinks you’re dead. It couples that with a possibility that has chilled me ever since the day when, at far too young an age, I pulled down Poe from my dad’s bookshelf, looked at the Table of Contents, and turned straight to “The Premature Burial.” From her point of view, she’s still alive when the earth starts thudding on the coffin. From Deacon’s point of view? Yes, I think from his POV too.

From ours? The director, Agnieszka Wojtowicz-Vosloo, says audiences split about half and half. That’s how I split. Half of me seizes on evidence that she’s still alive, and the other half notices how the film diabolically undercuts all that evidence. I think the correct solution is: Anna is a character in a horror film that leaves her state deliberately ambiguous.

Neeson’s performance as Deacon is ambiguous but sincere. He has been working with these people for years. He explains he has the “gift” of speaking with them. And little Jack, the eyewitness? Oh, but Deacon thinks he has the gift, too. So once again, you don’t know what to believe. Perhaps the gift is supernatural, or perhaps it’s madness or a delusion.

The film has many of the classic scenes of horror movies set in mortuaries. The chilling stainless steel paraphernalia. The work late at night. The moonlit graveyard. The burial. The Opened Grave. Even her desperate nails shredding the lining inside the coffin — although we see that from Anna’s POV and no one else’s.

I think, in a way, the film short-changes itself by not coming down on one side or the other. As it stands, it’s a framework for horror situations but cannot be anything deeper. Yes, we can debate it endlessly — but pointlessly, because there is no solution. We can enjoy the suspense of the opening scenes, and some of the drama. The performances are in keeping with the material. But toward the end, when we realize that the entire reality of the film is problematical, there is a certain impatience. It’s as if our chain is being yanked.