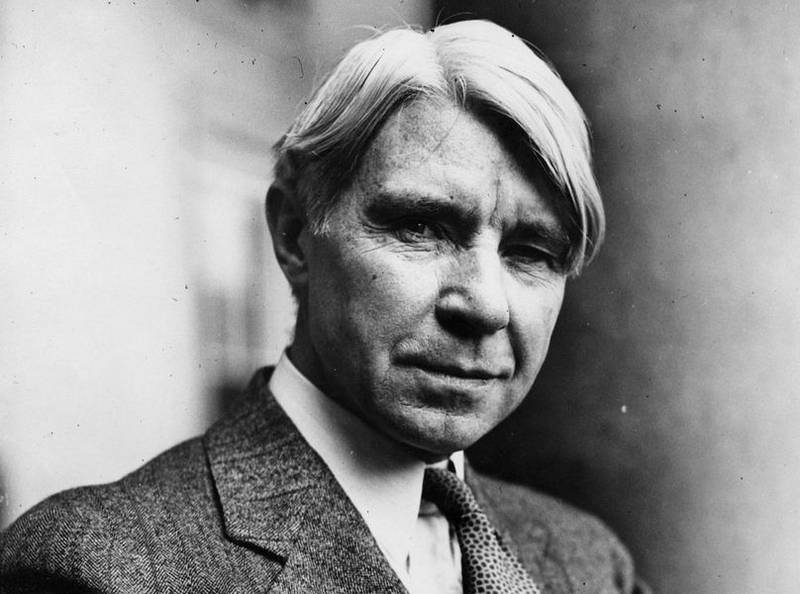

This is Ebert’s introduction to “The Movies Are,” edited by Arnie Bernstein, a collection of Carl Sandburg’s film criticism from the Chicago Daily News.

I am writing these words in Michigan, at our summer home. This morning as every morning when the weather permits I walked down wooded lanes that took me to Poet’s Path in Birchwood, the road leading past the home where Carl and Lillian Sandburg lived from the late 1920s until 1945, when they moved to North Carolina. Their house still stands, defiantly in violation of later regulations about height and position, its foundations cut into a dune. On the land side it rises five stories, on the Lake Michigan side three, a New England shore house with a widow’s walk on the roof.

I have been up there, climbed the ship’s ladder to the lookout over the lake to the west and the ravine to the north that carries into the lake a creek that generations of children have redirected with dams of sand. I know this because two of those children, Rob and Rick Edinger, are my neighbors, born on the property they still occupy, and when they were boys they used to dam the creek, and milk Lillian Sandburg’s herd of goats, which won blue ribbons at the Berrien County and Michigan State Fairs. A recent owner of the Sandburg house showed me its most unusual feature, a fireproof walk-in bank vault which Sandburg installed to protect his collection of Abraham Lincoln papers and manuscripts. He did not trust the volunteer firemen to arrive in time.

During his residence in the house, Sandburg was writing the third through fifth volumes of his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Lincoln. The owner showed me a photograph of the author, bare-chested, sitting in the sun on an upended orange crate on a topmost deck overlooking the ravine, writing on an improvised desk. Rick and Rob remember his daily walks on the beach, when he seemed so deep in thought he hardly noticed the world around him. They have both told me, and swear it is true, that one day as a joke they persuaded a tall friend to walk down the beach dressed as Abraham Lincoln in frock coat and top hat. “Good morning, Mr. Sandburg,” the figure said. Sandburg glanced up and said, “Good morning, Mr. Lincoln,” continuing on his way.

The Michigan years came as Sandburg, by then nearly 50, had enough of an independent income to free himself from daily journalism. The first volumes of the Lincoln biography must have supplied the couple with funds to move to Michigan and buy a substantial house (larger and more imposing than their home in North Carolina, judging by photographs of it).

Commuting to Chicago in those days would have been by the interurban South Shore Line, which came as far as Michigan City, Indiana, before curving down toward South Bend. That would have been an hour’s drive to the station in those days; perhaps it was quicker for them to go up to Benton Harbor and take the ferry across–the same ferry that brought Saul Bellow’s Augie March to his summer adventures in Michigan. Neither route would have been that quick, and perhaps the Sandburgs were happy be free of Chicago and daily deadlines.

It has been widely known that Sandburg reviewed movies for the Chicago Daily News, but I confess I thought he did it only occasionally. Now here is this huge book of his reviews, which even at some 400 pages provides only a portion of his output. These collected reviews show that Sandburg was not a hobbyist in his film criticism, but a professional who worked hard at it for eight years. Arnie Bernstein says that Sandburg saw the movies on a Sunday and wrote his week’s reviews the same day, which, even allowing for the shorter running times of most films in those days, made up a long day’s work. (His haste at times is perhaps revealed by the Harold Lloyd picture he praises but neglects to name.)

Many of the programs, especially in the Loop and in the ornate Balaban and Katz neighborhood palaces, would have been supported by stage shows, vaudeville or orchestras, but the live performances were not usually reviewed by Sandburg, perhaps because the Daily News had another man assigned to that task.

Chicago in the 1920s and earlier was the hub of several vaudeville wheels, including Radio-Keith-Orpheum, which sent the Marx Brothers revolving through the small cities of Iowa and Illinois. When I interviewed Groucho Marx in 1972 he recalled going to the movies with Carl Sandburg, adding that the theaters were warmer than the rooming houses where his mother Minnie lodged the brothers. “He would fall asleep and I would wake him up after the movie was over and tell him what it was about,” Groucho told me, but he was kidding. Sandburg was an attentive and observant critic, and moreover, his reviews lack the mischief that Groucho no doubt would have supplied.

One thing you notice, reading through this almost daily coverage of the emerging art form, was that Sandburg took film matter-of-factly. Today shelves groan under the weight of analysis of the silent period, the comedies alone occupying dozens of volumes, but to Sandburg they were not timeless art but movies, meant to be enjoyed; one senses he did not think they were as important as the older arts he considers in his Collected Poems, where there are many poems about writers, artists, musicians and all manner of tradesmen and citizens, but hardly any about the movies.

It is interesting that two of the poets most associated with Illinois, Carl Sandburg and Vachel Lindsay, both devoted a great deal of their time to film criticism. Lindsay’s book “The Art of the Film” collects longer essays of a theoretical nature, in which he was able to look at the earliest films and detect trends that are still visible today. Sandburg takes the view not of a theorist but of a daily newspaperman whose job is to steer readers toward the good movies and away from the bad ones.

One of his strengths is in seeing the importance of movies as a popular phenomenon. “Is it possible that an extraordinarily good motion picture play can be made from a Harold Bell Wright novel?” he asks, and the answer is yes. He writes: “Culturally speaking, there are arguments to be made that Hollywood–for real or woe–is more important than Harvard, Yale or Princeton, singly or collectively.” He keeps an open mind when going to movies of the broadest possible appeal. He likes Tom Mix’s horse, Tony, almost as much as Tom Mix, and then develops an enthusiasm for Tom’s dog, Duke. But it is possible to detect a smile, and perhaps a whiff of Mark Twain, in his writing about a picture like “The Sheik”: “The book had sentences such as ‘Kiss me, little piece of ice,’ but all lines like that were cut out of the movie and it was so different in that respect from the book that it was a disappointment to all who read the book on account of how wicked it was.”

There are also echoes of Twain’s uncoiling colloquialisms, with a zing at the end, in this wonderful long sentence from his review of a film of the Dempsey-Firpo fight: “Some think Dempsey is knocked through the ropes, and then comes back through the ropes, there is some guessing about where he has been in the meantime, while he has been gone, who picked him up, what they said to the champion, whether he thanked them kindly, and if the Marquis of Queensbury rules cover the point of who shall help and how much they shall help and in exactly what way they shall help a fighter knocked through the ropes and off the platform.”

Many of Sandburg’s lines conceal sly depths. One of my favorites: “The acting of Lillian Gish in ‘Orphans of the Storm’ is believed by some of her friends to be the best she has done.”

Sandburg shared the opinion, universally held at the time, that Chaplin was a genius and Lloyd and Keaton only very good clowns. He wrote that each relied on specialties: “Chaplin on his supreme talent as an actor, Lloyd upon novelty and Keaton upon droll ‘gags’.” That Buster wears better today as an actor might surprise him, but at least he knew how good Keaton was. As Bernstein points out, Sandburg preferred William C. de Mille to his elder brother Cecil B. (he bet on the wrong pony in that race), and shows an ease in moving between genres as he suggests C. B. might profitably study Keaton’s “My Wife’s Relations” and “learn something.”

There are a lot of interviews here, as Sandburg talked to luminaries on their way through town. In those days and for decades later, until jet planes replaced train travel, stars and directors took the Sante Fe Super Chief to Chicago, lunched with the press, and then continued to New York on the 20th Century Limited. He spoke with his hero von Sternberg, his favorite William de Mille, and Constantin Stanislavski, the great theater director, who told him in 1923 that the movies “have not even begun to be an art.” (This in contrast to Stanislavski’s countryman Tolstoy, who before his death in 1910 was already predicting that film would take the place of the novel in the new century.)

Sometimes Sandburg is a schoolmaster, praising “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” for its artistry and its Lon Chaney performance, but flunking its inter-titles: “And why spell forsworn wrong? Why not use some other word you know how to spell rather than bluff?” At other times he is simply a fan, and his greatest enthusiasms stand up to the test of time. He says he has seen Fairbanks Senior’s “The Thief of Bagdad” three times, and wants to see it three more, and his praise is Whitmanesque: “Old and young enjoy it and derive new health from it.”

Sandburg left the movie beat in 1928, which was the year when silent films died. It was also “the greatest year in the history of the movies,” according to the director Peter Bogdanovich, who featured its films in a revival program at the Telluride Film Festival a few years ago. If he is right, 1928 saw the summit of silent art, followed by the cramped compromises of the early years of sound. Sandburg took the transition in stride; he observed in November 1927 of “The Jazz Singer” that “The vitaphone did a great deal to help, reproducing the songs and some of the other sounds in the course of the action.” He resists the temptation to quote “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet.”

Arnie Bernstein has performed an extraordinary accomplishment in bringing this book into being. Having tried to track down some of my own relatively recent reviews I know what a scandalously bad job is done of preserving runs of daily newspapers. All of these reviews had to be located, identified and transcribed. To that enormous task Bernstein adds great knowledge and insight in his introductions to the reviews, providing background, orientation, historical information, helpful footnotes. This is a book that reopens a chapter of journalism and history that might have remained closed forever.