The jury press conference is a Cannes opening day milestone, and this year’s jury is rather revolutionary for the tradition-bound festival. It is headed by a woman, New Zealand director Jane Campion (“Bright Star,” “The Piano“), and boasts five women to four men: Carole Bouquet (France), Jeon Do-Yeon (South Korea), and Leila Hatami (Iran); actors Willem Dafoe (USA) and Gael Garcia Bernal (Mexico); and directors Sofia Coppola (USA), Nicolas Winding Refn (Denmark), and Jia Zhangke (China).

Approvingly citing Thierry Fremaux’s pride in the fact that twenty percent of the competition films are by women this year (meaning two out of eighteen), Campion said, “I think you’d have to say that there’s an inherent sexism in the industry. It does feel very undemocratic. Time and time again we don’t get our share of representation.”

This group comes off as one of the more likable Cannes juries in memory: clear-headed, good-humored, and unimpressed by their own importance. There’s very little for them to say when they have yet to see a single film, so the public forum is essentially a bantering session about the art of competition. “I remember that this is a game, and then I start to enjoy it,” quipped Bernal.

Campion, who might be described as no-nonsense in the fashion department, deflected a question about the jury process with, “My big problem is what to wear. There’s a very high quotient for glamour here.” As if underlining the jury’s lack of pretension, their dress code was casual, especially for the women, to the point that Coppola wore a simple Oxford-cloth short-sleeved shirt. There was a conspicuous absence of the borrowed jewels that female jury members typically flash.

Today is the last time we’ll be hearing anything from this jury until closing night. The president makes the rules, and Campion’s rules for her fellow jurors were clear: see all the films, give no interviews and read no speculation while the work is underway. “We won’t be reading what YOU say,” teased Bouquet to the assembled press.

Cannes is above all an international experience, a fact that is driven home every day in every festival lineup of critics scrambling for entrance to a screening or press conference. As the throngs mass for the preview screening of “Grace of Monaco,” tonight’s opening film for the 67th Festival de Cannes, I eavesdrop on the multi-national patchwork of conversations around me. “I understand his life was quite complicated,” says one serious Brit to another. A tall guy wriggles his way through the pack while exchanging shouted pleasantries in German with someone distant. “Di-anne Keee-ton,” insists a diminutive Italian woman over and over in animated dialogue with her cigarette-wielding companion.

The first impression of the Riviera coast from a plane is one of blinding sparkle. It’s all blue sky, blue water and masses of yachts in a hard white light that delineates the craggy cliffs and steep hills that rise above a continuous string of harbors from Monaco to Nice and Cannes to the west. By contrast, “Grace of Monaco” by French director Olivier Dahan (best known for “La Vie en Rose“) is thick with the old-timey amber light of the past as the movies stereotypically see it.

“Grace of Monaco,” starring Nicole Kidman in the title role, is a fictionalized portrait of a critical juncture in the marriage of American movie star Grace Kelly to Prince Rainier of Monaco. The film has been surrounded in controversy. Earlier this year it was announced for pre-Cannes U.S. release then withdrawn. The three children of the royal couple have denounced it unseen. No chance that Prince Albert of Monaco will be escorting Kidman on the red carpet tonight, I surmise. “I feel sad because the film has no malice toward the Grimaldi family,” declared Kidman at film’s press conference.

Those looking for either brilliance or insight from this “Grace” were disappointed by the mediocrity of a film ripe with pop psychology and a made-for-TV air that triggered a plethora of unintended guffaws. In the credit sequence Grace Kelly (Kidman) completes her final day on the set of a Hollywood film. Jumping ahead six years to 1961, bored, unhappy Grace is now a virtual prisoner as royal wife and mother. Her husband Prince Rainier (Tim Roth) reprimands her for sassing a French official at a party on the Onassis yacht; the palace staff members disdain her as a blundering commoner. Hitchcock visits and offers her the lead in his new film “Marnie.” She wavers.

“Grace” sets up two lines of conflict, both rendered more than a little silly in the realization. As adversaries, there’s Madge, a stiff-necked lady-in-waiting (a relentlessly stern Parker Posey), a Machiavellian sister to Rainer, and a sneering countess. Torn between the need to please her husband, a tyrant at home and a milquetoast in the political realm, and the desire to return to the screen, the princess belatedly begins to study her role as consort to a head of state with a somewhat amusing Derek Jacobi as her aristocratic teacher. As she struggles with French lessons, Dahan cuts away to a pet parrot. Yes, it’s that kind of film.

On the political side, Monaco is under siege by French president Charles De Gaulle, who intends to annex the tiny nation over a taxation dispute. In heavily accented English, De Gaulle (Andre Penvern) threatens, “I’ll send Monaco back to the Dark Ages,” for the film’s best inadvertent laugh, as the crisis escalates to apparent Doomsday proportions. Ultimately, Grace gets a grip in a stiff-upper-lip kind of way, resolves her personal crisis by giving up Hollywood, and defuses the political mess by inviting De Gaulle to a charity ball where she gives a soul-searching speech.

“Grace of Monaco” is forgivable in the shorthand approach of its superficiality, but unforgivable in the weight of its relentless clichés. Kidman is showcased in a wealth of close-ups and a fortune in authentic Dior fashions and Cartier jewels, but is little more than a two-dimensional figure who is often reduced to mugging. The term “fairy tale” is thrown around a lot, but this film could have used a fairy godmother screenwriter and a better director.

Festival director Thierry Fremaux ushered Dahan and principal members of the cast into the “Grace of Monaco” press conference. Kidman looked oddly like an adult Alice in Wonderland, wearing a full-skirted white dress, and with blonde hair arranged in a long, school-girlish style. Someone asks Tim Roth, “Is there a moment when you felt like hitting Her Serene Highness?” “What a strange question,” the astonished actor replied. Kidman was asked if she would give up acting for love like Grace Kelly. “I would, absolutely,” she declared.

Just as things loosened up it was over. “Hey Nicole,” one journalist bellowed, getting her laughing with a question along the lines of glamour and sex, fairy tale and dreams. “I like the way you say the word sex,” she answered with a provocative smile.

While hordes gathered in the evening to get a glimpse of Nicole Kidman and company ascending the red-carpeted steps at the Grand Theatre Lumiere, the rest of us were trudging up a more humble red carpet for the press screening of “Timbuktu,” the first official competition press screening, by Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissoko. Like “Grace of Monaco,” the film aims for the shorthand of stylization, but with much better effect and with sobering impact.

“Timbuktu” is set in a West African village in Mali that has been invaded by a group of Islamic extremists who quickly establish themselves by force as the new rulers, perpetrating atrocities and destroying a peaceful way of life. The film opens with a sequence in which a band of the strangers, faces swathed in scarves, hunt a panting deer from a speeding pickup truck, machine guns blazing. In the next shot, with those same guns the men demolish figurative tribal carvings, many of them images of women.

Sissoko tells the story bluntly, yet with poetic irony. In a film that might have been marked by righteous anger and strident moralizing he is deliberate and careful. There is both beauty and eeriness in shots of the masked figures stalking the village by night or announcing the list of forbidden activities in deserted streets by day. The Arabic-speaking invaders are so alien that they require interpreters to relay their dictates to the locals.

The performances have a starkness that seems to make time stand still in the gravity of the film’s mounting contradictions. When soccer is forbidden the undeterred men devise a fantastical pantomime game. When dance is forbidden a man performs a lonely improvisation for an audience of one, the village madwoman. When music is forbidden one of the guilty wails her song while being publicly flogged.

Against this background, a family of three is destroyed when the father, Kidane, a young herdsman, accidentally kills his neighbor in the course of an argument over a dead cow. Through this plot line Sissoko brings the moral contradictions into even sharper focus. Those who serve as his judge and jury often violate their own proclaimed beliefs with impunity, and one of their number even lusts after Kidane’s wife. In a lyrical but disturbing image that echoes the film’s opening, his orphaned daughter runs panting across the sand hills.

With this two-film Cannes launch, it was a good day and a bad day in terms of quality; i.e. a typical day here on the Riviera. Tomorrow the festival kicks in full force in all its good and bad bounty.

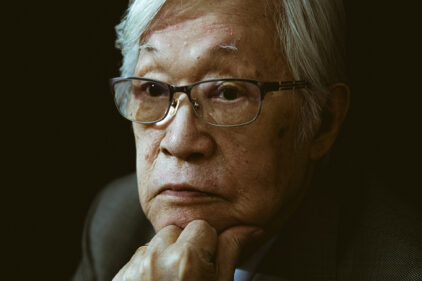

(Jane Campion Photo Credit: Anne Demoulin)

Read the rest of our coverage of Cannes here and don’t miss the following special events at the festival:

Screening of “LIFE ITSELF,” in Cannes Classics: Monday, May 19, at 5 pm in Bunuel.

IN CONVERSATION with Steve James and Chaz Ebert about “Life Itself,” at the American Pavilion, Wednesday, May 21 at 11 am.

THE ROGER EBERT FILM CRITICS PANEL: at the American Pavilion, Thursday, May 22 at 3 pm. Moderated by Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune), including Eric Kohn (Indiewire), AA Dowd (The Onion AV Club)