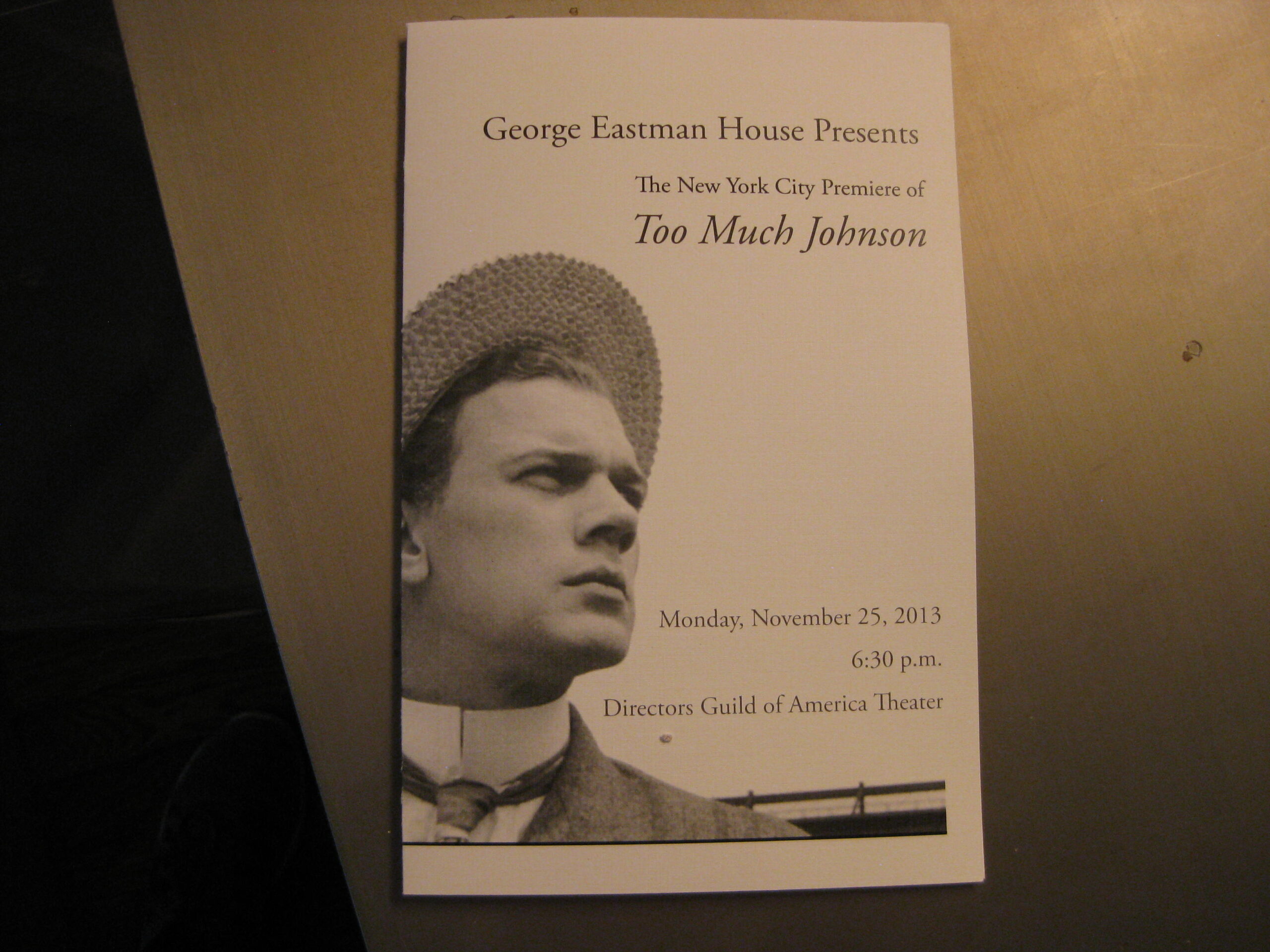

Only 75 years late, the presumed-lost, recently rediscovered footage from Orson Welles’s 1938 stage-and-film production “Too Much Johnson” had its New York premiere last Monday night. And in at least one sense, the “too much” was apt: Welles never completed the movie portion of the piece, so what we have, at 66 minutes, runs significantly longer than what he intended to be seen.

Shot when Welles was around 23 and conceived as an homage to silent comedies, the filmed segments of “Too Much Johnson” were to be screened in three separate parts; each section would serve as a prologue to an act of William Gillette’s snickeringly titled 1894 farce. As Bruce Barnes, director of the restoration-heading George Eastman House, explained before the screening, the first introduction would have run 20 minutes, and the second two would have run 10 minutes each. Alas, owing to possible fire code issues with the nitrate film stock, the lack of a viable projection setup, or perhaps other complications, the play premiered at Connecticut’s Stony Creek Theater without the use of any footage—a gambit that doomed it to incomprehensibility and scotched its chances of a Broadway run.

Never designed to be a standalone piece, what remains of “Too Much Johnson” might most accurately be referred to as “the filmed prologues of ‘Too Much Johnson.'” Because the found reels come from a workprint, the current edit often includes multiple takes of the same shot, and many sequences clearly stretch longer than they would have at completion. Even in its rough form, though, Welles’s first commercial movie production showcases a surfeit of the director’s genius, providing a fascinating window on his earliest screen work with the nascent Mercury company as well as a preview of things to come three years later in “Citizen Kane.”

Representatives of the curatorial team—Paolo Cherchi Usai, Caroline Yeager, Daniela Currò, and Anthony L’Abbate—narrated the piano-accompanied screening with trivia, plot information, and notes on locations. The story revolves around the romantic deceptions of Augustus Billings (Joseph Cotten), who passes himself off as a Cuban landowner named Johnson in order to facilitate an affair with a married woman (Arlene Francis). The end of the first prologue finds the key players setting off for Cuba, where an actual plantation owner named Johnson (Howard L. Smith) enters the picture.

Welles fashioned the film as a throwback to the era of silent comedy. The two leads wear Harold Lloyd–style straw hats, and there are moments of life-risking slapstick reminiscent of both “Safety Last!” and Buster Keaton. Some of the comic scenes with crowds recall “Seven Chances”; Joseph Cotten’s rooftop balancing act with a ladder makes it amazing he survived to collaborate with Welles again.

The first of the three prologues is the longest and most complete from a narrative perspective, and consists largely of an extended chase sequence, as the cuckolded husband (Edgar Barrier) pursues Billings over roofs and through markets, streets, and eventually a suffragettes’ parade. Among other things, the movie offers a wonderful visual record of New York in 1938; the restorers have gone to great lengths to identify the original filming sites, which include such long-gone backdrops as West Washington Market and Marie Curie Avenue, which was replaced by the FDR Drive.

Given the fantastically inventive use of soundstages and optical tricks in “Kane,” one of the striking things about “Too Much Johnson” is that it’s mostly made up of exterior shots. As filmed by newsreel photographer Paul Dunbar, the movie provides a fascinating glimpse of Welles’s visual sense before he teamed up with “Kane” cinematographer Gregg Toland. In contrast with the tunneling deep focus of Welles’s feature debut, many sequences have a documentary realism. There’s seldom a sense of privileging the upper-right-hand quarter of the screen, a “Kane” attribute Roger Ebert used to discuss in his master classes on the film.

Still, Welles’s dynamism is ever apparent: In a market scene, Cotten and Barrier pursue each other through a pile of baskets that resembles the detritus in the finale of “Kane.” A shot of crisscrossing clotheslines in a tenement courtyard conveys a recognizably Wellesian sense of angularity. As the characters set sail for Cuba from Battery Park, there’s a striking low-angle shot of passengers on the departing ship waving goodbye.

Some of the footage is in poor shape. We were told that the reel in which Barrier attempts to find Cotten by knocking straw hats off random men in the street had decomposed almost to pure nitrate; even now, the image is substantially pockmarked. The second and third prologues are less fully assembled than the first. Act two begins with a stunning day-for-night shot of a sunset over “Cuba” (most of which was faked in a quarry in Haverstraw, New York), then introduces us to a pre-“Kane” Erskine Sanford, whose character visits the grave of one of Billings’s friends. Act three begins with a duel, in which theater legend John Houseman serves as a stunt double. (Earlier, Houseman appears as a bumbling cop; this sort of performer recycling can also be seen again in “Kane,” in which Sanford and Cotten are visible—not playing their characters—in the screening-room audience at the beginning of the film.)

Plans for “Too Much Johnson” are still evolving, but there’s talk of digital restoration for the decomposed segments, an Internet release, and possibly even a staged version accompanied by some of the footage, trimmed to approximate what might have been Welles’s intended form. But for now, these fragments make for an unmissable live event. Monday’s screening at the Directors’ Guild of America theater was only the second U.S. showing, after one in Rochester in October; the presentation premiered earlier that month at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy. It’s not the lost reels of “The Magnificent Ambersons,” but for now, “Too Much Johnson” offers much (and then some) to ponder.