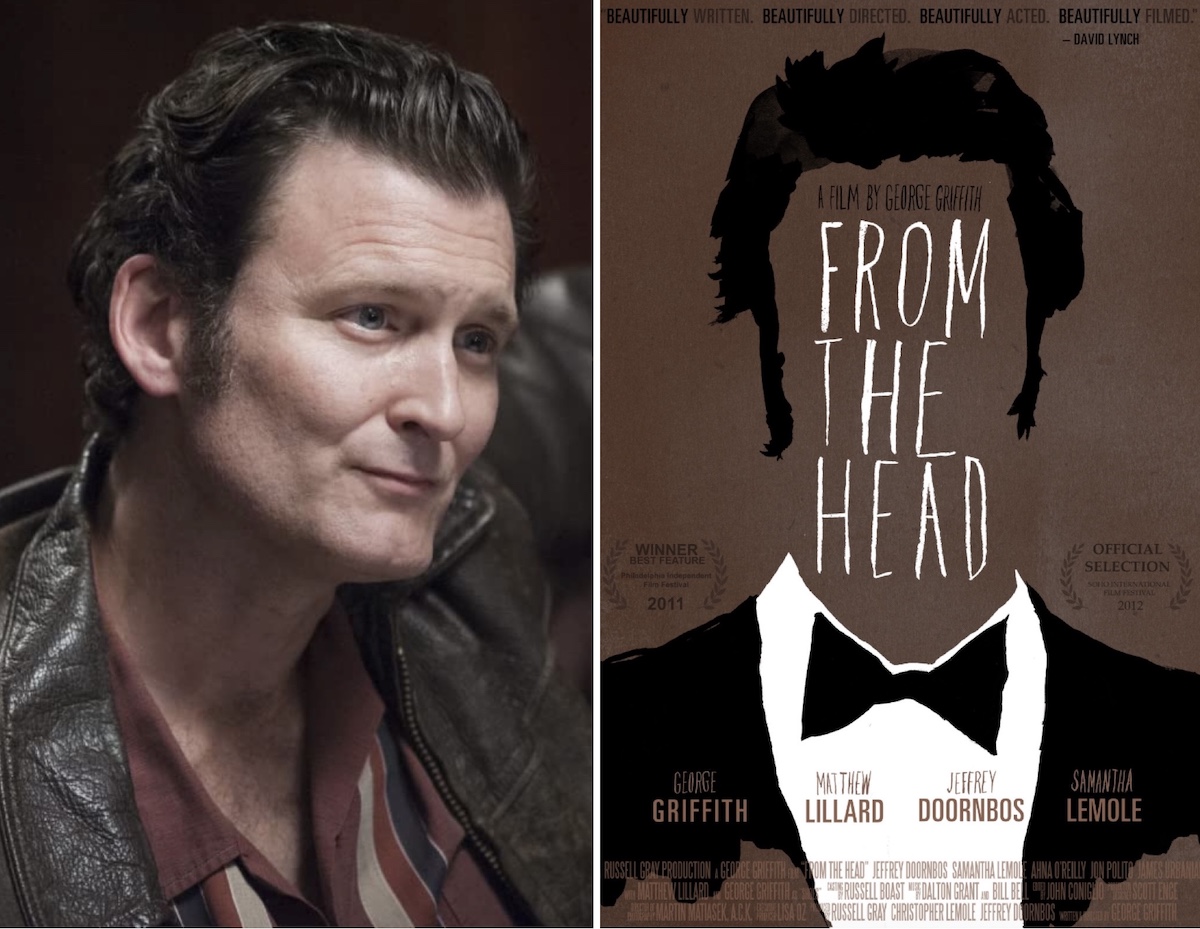

You never know who you’ll meet at the Double R Diner. This past February, my wife and I traveled to North Bend, Washington, for The Real Twin Peaks festival, which I attended with two other devotees of the show, my brother-in-law and his girlfriend. No sooner had we arrived at Twede’s Cafe, the actual location that served as both the interior and exterior of the Double R on all three seasons of “Twin Peaks,” than in steps actor George Griffith with his equally impressive partner, Iggy Pop guitarist Sarah Lipstate. Griffith brilliantly portrayed Ray Monroe, an associate of Mr. C. (Kyle MacLachlan in a chillingly evil 180 degree turn from his comedic innocent, Dougie), who conspires against him with his partner Darya (Nicole LaLiberte), on five episodes of “Twin Peaks: The Return,” while the show’s co-creator David Lynch reprised his signature role as FBI Regional Bureau Chief Gordon Cole.

Upon introducing myself to Griffith, he gave me a copy of his superb 2011 directorial debut, “From the Head,” in which he inhabits the semi-autobiographical role of Shoes, the charismatic bathroom attendant at a strip club. The film will be screened in 35mm this Wednesday, May 31st, as part of “David Lynch: A Complete Retrospective,” masterfully curated by Daniel Knox at The Texas Theatre in Dallas. I recently spoke with Griffith via Zoom about the film, which received praise from no less than Lynch himself, as well as his experience of filming one of the greatest hours of cinematic artistry ever to air on television.

It was so serendipitous how we met at the Twin Peaks festival in February, where I had you pose with the poster from Daniel Knox’s Lynch retrospective in Chicago. Neither of us knew that you would be in his next one.

All of it has been very dreamy for me, the way that things have happened. I met David on April 1st, 2009, when I interviewed him for Sirius radio. David’s book Catching the Big Fish had come out, and it contained a different kind of voice from him. I had been a fan of his all along, so as you probably do, as things would come out, I would acquire them and devour them. The book really effected me a lot, and got me thinking, ‘Maybe I should meditate because I’m not really together.’ So I approached a radio show that I had a connection to and requested that they have David on for Catching the Big Fish. They told me that everyone was trying to do that because it was a new book. There was going to be a concert with Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney and other people who had been connected to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in New York, and David was going to be there for it, so he agreed to be interviewed for the show when he was in town.

When that had been confirmed, I prepared an “if then, go to” document. I started meditating and I connected many things that he had said over the years as well as discussed in the morsels of Catching the Big Fish to his films. Lynch on Lynch was a book I had reread many times. It’s so good and so refreshing and I love his perspective on things. I think it’s inspiring. I also read Maharishi’s book and at that point, I had done a ton of research on Transcendental Meditation because there were plans to have it put into schools in California. That interested me because if I had access to it as a kid, I think I would’ve had a different path. I would’ve been more relaxed in life. So I created this document and it became pretty hefty with directions like, “If David talks about this, you can ask about ‘Lost Highway,’” and things like that. As it got closer, the people on the show said, “No one wants to learn all this. Do you want to come do the interview?”, and I was like, “You bet.”

Oddly enough, David and I both flew from LA to New York on the same day. I introduced myself, and we started talking about Philadelphia because I’m from Philly. It felt like talking about his old favorite love. Then during the interview, I was able to have a lot of agility in discussing things with him, and ended up having lunch with him afterward prior to his flight back. I kind of aggressively acquired the seat next to him, and whenever there would be a lull in the conversation, I’d ask things like, “Are you really never shooting on film again?” I also told him that I had the idea for a feature that would take place entirely in a bathroom, and he just said, “Great.” I was like, ‘Wow, no one has reacted that way when I’ve said that before.’ [laughs] He said, “Keep final cut,” and of course I knew that was the way he felt, but for him to say that to me, I was like, ‘You know what? I’m going to do that.’ I asked David if I could send the film to him when it was finished, and he said, “Yeah, buddy.”

At this point, we had been together for three or four hours and I felt pretty confident that we were having a nice rapport and that he liked me. Later on, his assistant told me that David thought I was funny. It’s hard to keep final cut in a contemporary circumstance, particularly as a first-time filmmaker and an auteur who doesn’t have any prior credits. The greatest thing I think we can do is trust people who have a vision. If it’s going to be bad, let it be bad. If it’s not going to work, that’s fine, but let’s not make this a democratic kind of endeavor. I think that is a disaster. Of course, I wished at the time that my film blew up or had gone to Cannes or something crazy like that, but what I was always really proud of and grateful for was that I listened to him and that I did keep final cut. “From the Head” comes up very frequently in social media and in conversations since “Twin Peaks,” and I never have a moment of shame or embarrassment or anything like that.

I’m also really proud and happy that people are going to check it out, especially cinephiles because I am one. I grew up in a house of cinephiles, and that’s who I made it for. I shot it anamorphic so that it would look great in a cinema, which even at the time that I made the film was really a dying endeavor. The things that I watched with my DP Martin Matiásek were films I had seen on the big screen, such as “There Will Be Blood” and Pasolini movies. I loved how the faces of people were filmed and the way scenes were lit. I always thought that my film was going to be beautiful on the big screen and I think it is. I have seen it on the big screen a few times, but never in a film print, so I can’t wait for that.

Having an entire film from the perspective of a bathroom attendant, who spends the majority of time in a space where people are quickly entering and exiting, is a narrative masterstroke in how it causes us to linger on and empathize with people we would normally have very limited interactions with.

I agree with you and really appreciate that observation because my intention was to smuggle a road movie into this situation. “From the Head” is a road movie, it’s just that the road goes past him. It’s like those old movies where they would crank the scene behind him. He stays put there while everything keeps moving around him in real time. When I was in there, I felt like I was in the driver’s seat because it was my own little world, and I definitely knew I was going to do something with that material as an actor. When I got out of conservatory, I had a lot of different jobs such as carpentry, but I just wasn’t cut out for being a waiter.

I was working at a pretty nice joint, but I had gotten a bad attitude about it, so I quit abruptly, and I was definitely living hand to mouth. I was doing a play at the time and suddenly had all of these bills to pay along with my rent. The question, ‘Oh, why didn’t you think that through?’ would run through my mind many times every day at that point in my life. [laughs] I was offered the job of a bathroom attendant in a theater, and eventually agreed to do a shift. My employer said, “Just do it for a little while. Nobody can last,” and I took that as a little bit of a challenge. I was also a pretty ravenous reader at the time, and I wrote a lot. I was interested in having a journalistic element to my fiction so that I could sort of be like, ‘Well, it did kind of happen.’

That wonderful quote you have from Samuel Beckett’s Molloy at the beginning of “From the Head”—“Perhaps I’m inventing a little, perhaps embellishing, but on the whole that’s the way it was”—must’ve informed your whole approach.

Absolutely, and thank you for acknowledging that because I remember when I got the permission from the author’s estate, they didn’t really know how to address it because no one had ever used a Beckett quote like that before. I also thought that there was very quietly a Celtic kind of storytelling in my writing, and I think he is one of the great Irish writers. I read “Molloy” when I was working in the bathroom—I read a lot in that job—and I recognized immediately that the people I would encounter in there were providing me with a gold mine of material. I still had my Dale Cooper-style tape recorder from high school that my mom had gotten for me. She knew that I loved “Twin Peaks” and since I couldn’t keep up with my thoughts when I was writing, she gave it to me. I would tape it inside my vest in the bathroom during an eight-hour shift, and when some dude came in, I would turn it on. Then I would come home, where I had one of the first little Macs under my bed, and I’d transcribe the whole thing for another four hours and try to piece together the good stuff, which was pretty much everything. I’d even pass it on to the guy who came in after me and say, “I think you’ve got a different group of guys than I do. Now I’m getting repeats.”

I did this for a year, and then I lost everything on the computer when it died. I was crushed and thought, ‘The hell with that idea anyway. No one is going to believe any of it, and nobody is going to care about a film set in a bathroom.’ But then, many years later when I had moved to LA, I was talking to a friend who I was rehearsing with for a project, and we were joking about past jobs. When I mentioned that one, she was like, “You have to write about this,” and her level of curiosity was intriguing to me. I went home, started writing and it was like a gusher. I could hear the voices of the characters readily and I just kept writing scene after scene. My grandmother and my dad were great storytellers, and after living in Philly, I know that the people there would never let the truth get in the way of a good story. I’d be in a bar three nights a week and when I heard the same story being told, I’d be like, ‘Damn, this gets better every time.’ That’s why I chose the Beckett quote because what happens in the film is largely very true, but I worked it over and massaged it like you do.

Your performance anchors every scene, and it reminded me a bit of Gabriel Byrne’s therapist in HBO’s “In Treatment,” who has to keep his emotions in check while interacting with his patients.

I did do myself a service. Since the film takes place in real time, I was in every minute of the movie, and we were shooting over 18 days, I immediately made sure that we could shoot in sequence, which is unusual for a film. But because of the nature of the way that people appear, it wasn’t that complicated schedule-wise because there are only a few people other than Shoes who appear more than one time. I’d be coming back the next day and we were picking up the next second of what just happened yesterday, and since “From the Head” is a slow burn for my character, I felt that approach was critical. The screenplay was kind of underwritten—it was largely dialogue—but I knew how the day and the job and the people and the drinking and the environment were all going to wear on him, so what I had to do was make sure I created a production environment that would facilitate it and support it. It was hard to tell on the page what a rough day it was going to be on him.

Another quality you share with Lynch is your embrace of prolonged, charged silences in which a great deal is conveyed without dialogue.

I think that is really astute of you because I said many times to the actors and producers that one of my greater fixations in terms of characters and storytelling is on everything that we don’t say. I think even in relationships and in life, that’s where you can find out a lot, and that’s why listening is a real skill. My character is put in a sort of circumstance where listening is also tethered to his revenue, so there is a mercenary element to what he does and how he approaches it. It’s easier to keep your energy if you allow things, and I think that’s something that he’s learned from doing the job. From an editing standpoint, I had to assert myself a few times. My editor John Coniglio was amazing, but the producers and people who were watching it in the beginning were critical of scenes that took a longer than usual time. I think that those moments are gifts for viewers and certainly for me. Those are the times that you can daydream and you can have things really happen to you as someone who is witnessing.

If we move too quickly to the next thing, there can be some sacrifice to things that could maybe really land and settle and I also think that it jeopardizes the power of empathy. I ask every bathroom attendant that I ever meet, “Have you seen my movie?”, and they’ve never seen it, and I always tip ‘em really, really good. My hope was that the film would connect with anybody who feels stuck in their job and perhaps drowning in the melancholy of lost potential, and it was imperative that we allowed the time to linger on certain moments, such as when the people leave and we stay with Shoes. That’s when his predicament can infiltrate you more. Also, by filming it in real time and having a ceiling on the set, which is unusual, I wanted to have the feeling of what it was like to be stuck in a place that you have to be but you don’t want to be.

It’s interesting how my three favorite films—“Mulholland Dr.”, “It’s a Wonderful Life” and “The Shining”—are also about characters who are stuck. Cinema enables us to empathize with that sort of experience in a way that is cathartic.

A hundred percent. I have always been grateful for the gift art provides by reminding you that you’re not alone. You look at a work of art and think, ‘I can’t say it that way, but that’s what I wish I could say,’ or, ‘I don’t know if I could sculpt that but that moves me,’ or, ‘The way that paint is moving, I have no idea how they did that, but that’s how I felt when I lost that person.’ I think that there is real power to art in how it makes you feel connected, and in “From the Head,” all of the characters are desperate for connection. That world is saturated with that kind of motivation and desire, and I always felt like I sort of trojan horsed a movie about love in a strip club. These characters want to feel like they are a part of something. That craving for love and connection is really what keeps environments like that afloat as businesses, and it’s definitely what I wanted my film to be about.

One of the most touching sequences in the film features a 35-year-old man on the spectrum played by Clint Culp who feels plucked from life, much like the people who occupy the periphery of many Lynch narratives.

Many of the characters in the film were combinations of people I had met, but that one you’re talking about was based on a specific guy who came in, and I made an effort to ensure that there was no judgment on any of the people in the film. I certainly don’t mind a repeated likening to David Lynch because especially as time has passed, he’s been one of my greatest influences. I really appreciate the things that you’re bringing up because they are what I find moving in David’s work and why I keep returning to it. I can watch David’s films and keep finding new things. I wouldn’t call his characters “crazy.” They are nuanced. Maybe they aren’t the sort of people we meet most of the time, and that may be in part because we’re not always in environments where people feel like they can act like themselves, like they do in a bathroom with a guy that they’re never going to see again.

There was definitely a point where I was like, ‘That guy might recognize himself in the film,’ but the chances of him being like, ‘I was that regular who was there enough for this guy to remember me and write about,’ were low. But I did have people contact me via social media and say, “I remember you from the bathroom.” One of the women who worked there wrote about the film many years ago when she saw it, and she thought that it was pretty spot-on. That’s the reason why I set it in ’95 because I am an authority on the bathroom in 1995. That’s when I worked there and the film is based on the specific afternoon of a baseball game. You’ll notice that there are no baseball hats because we weren’t allowed to use the Yankees logo.

I was struck by how you and Matiásek used mirrors to open the space visually while playing with perspective.

I love that you’re bringing this up. I designed the set, so I had an aerial view of it and could direct the flow of traffic in the script. I wanted Shoes to be in front of the mirror and right away, everybody—the producers, the set designer and every DP that I interviewed—would say, “You’re going to shoot a whole movie with a six-foot mirror behind you?!” And I said, “I think we can do it.” I also had the idea of cutting the holes out in front of the urinals, which is why I put newspapers up in the bathroom. I knew I could cut a hole the size of a lens and the actors would block it while they were at a urinal so I could get those shots.

Marty and I got along really well and he helped me petition for the money we needed to shoot “From the Head” on film. We wanted the film to be cinematic rather than a filmed play, but without showing off. It was really wonderful to have so much trust in him because we planned everything before we got there, but as you know, crazy things happen every day. I had to deal with actors and my own lines while adding new scenes and shooting on film, of which I didn’t have an endless supply. I quickly did only one take of my stuff if it was clean because I had to make sure I had enough film for the other actors.

Your attention to sound design extends to the detailed ambience indicating what’s occurring outside of the bathroom.

I wrote a full separate script for the DJ so that he would always be making announcements. Other than the opening song, which I really love, I wanted the music to be of the time, but obviously I couldn’t pay for a soundtrack like that. I also had about sixty different descriptions of how the urination would sound for each character.

This is also a film of great faces, including that of the late Jon Polito and your “Twin Peaks” co-star Matthew Lillard.

Matthew is a very old friend of mine. I met him when I was 19. We were like the young guns at the conservatory that we were in because it was a graduate program, but neither one of us had done undergrad. We both sort of hotshotted our way in and we had a mutual admiration for each other. We were both risk-takers and adventurous in our choices as actors, and we remain close to this day. He did one of the web series that I had made to raise money for the feature.

I was being encouraged to have a little more of a cameo fest than I was interested in doing. I thought that would undermine the tone that I was going for in “From the Head,” but Jeffrey Doornbos, one of the producers, had just done something with Polito and was like, “You want me to ask him if he’ll come meet you?” He agreed to meet me at a cafe for coffee, and he had a scene with him that I had sent him. We’re talking for a couple minutes, the coffee came, and he asked, “Should we read it?” I said, “You wanna read it here?”, and he just goes for it. Afterward, he looks at me and says, “Let’s shoot this fucker.” [laughs] I was so pleased. He was a hoot onset, and wore a “Big Lebowski” shirt, which is one of the superstitious shirts he’d bring to a film shoot. I remember the guy who I based his character on, and Polito just crushed it.

I spotted the name of Valerie Weiss, an excellent filmmaker whom I’ve interviewed in the past, among the people listed in your Special Thanks credit roll.

Her husband, Robert Johnson, is briefly in “From the Head.” Valerie was a Harvard grad who was going to be moving into film, and she was the greatest person for me to know because I wasn’t good at educating myself about how to produce a film. She had a really brilliant perspective on how to get things done, and she introduced me to my first AD, Nick Harvard, who had just finished “The Hurt Locker” and was invaluable. He is still one of my best buddies. Val was just somebody that I would reach out to about things I was trying out, such as budgeting in reverse, and she was so smart.

Did the film premiere at the Philadelphia International Film Festival, where it won the Best Feature prize?

Yes, and that was a really beautiful thing because that is my hometown. They screened it at the art museum, which I went to my whole life, and projected it on the IMAX screen. It was the first time that nudity had ever been shown on that screen, and that premiere probably had the largest audience who ever saw the film. I was very humbled by how many people showed up to it. In Philly, people are like, ‘Local boy makes good, we will be there,’ and they definitely were, though tons of people also came down from New York. There were guys and girls that I went to grade school with in attendance because the screening was in the paper. It was magical.

What was your reaction to Lynch’s response regarding your film—“Beautifully written, beautifully directed, beautifully acted, beautifully filmed.”—and how did that lead to you being cast in “Twin Peaks: The Return”?

That line was part of a longer email that he sent me, and I was definitely fending off being down in the dumps. “From the Head” was not being accepted by every film festival that I was submitting to, and I was trying to tell myself, “At least I did it the way that I believe it needed to be.” I served the piece, I served myself and I served my vision because there is a lot of flotsam and jetsam that happens and I very successfully made it through all that. Then one day, I got David’s email and I just remember tears running down my cheeks. He said that everybody who was involved should be congratulated, and I just couldn’t believe it. I continue to write him letters on my typewriter, and we live pretty close to each other. Matthew and I had been in Steppenwolf West for a couple years, studying and working on things there, and in the summer of 2015, he came to me and asked, “Do you want to do a LaBute play? I’m going to direct it and I’ll cast around you if you do it.” I had done a lot of Neil LaBute productions—I sit pretty well in those unsavory pieces, and to me, he is one of the most brilliant playwrights. I feel like it’s almost effortless to ingest and to own.

Matthew had done a play with him a few years earlier in the U.K. So I agreed to do Neil’s first piece, Filthy Talk for Troubled Times, which is kind of hard-core, and then Matthew said, “If you think you’re up for it, there’s another play and I want to do them both at the same time in Scotland.” I thought, ‘How and why would I ever say no to such an amazing challenge?’ We hadn’t done anything together for a while, and I always found working with him to be really inspiring. It was challenging in an intimate, kind of familial way. Right as we were about to leave for Scotland, I got an email from David’s assistant asking for a copy of “From the Head.” Then I got called in for my meeting with casting director Johanna Ray, and I was really excited. I had written a letter to David when he and Mark Frost simultaneously tweeted, “The gum you like is going to come back in style” in 2014. I immediately grabbed my typewriter and blasted out a letter to him saying I could put my energy to any task on “Twin Peaks.” Then the next day, the show was suddenly no longer happening, and I was like, ‘Oh no—my letter’s in the mail!’ [laughs] Thankfully, it came back.

Anyway, I thought that Johanna calling me in was just a result of David’s kindness. Matthew and I were about to be out of the country for a long time, and we didn’t talk about going in for the audition. I didn’t want to talk about it with anybody because it was enough for me to simply be called in. While I was in Scotland, I got an email from Johanna requesting that I “put a pin in me,” which is kind of old school language for “don’t got anywhere for these dates.” I looked at it and thought, ‘Those are a lot of dates. I guess I won’t be pumping gas.’ I knew from the show’s executive producer Sabrina S. Sutherland that David had me in mind when he was writing Ray, and it’s difficult to articulate how that feels as an actor. I didn’t know that when I got my script—only after we were finished did I find that out. When Matthew and I saw each other at the premiere, he gave me the biggest hug because honestly, the truth is that he teased me a lot about how obsessed I was with Lynch when we were younger. When we were in our first year at the conservatory, and we’d be asked, “What do you want to do?”, our peers would be like, “There’s that new guy in ‘Thelma and Louise,’ I’d like to have a career like him.” And I’d be like, “I want to be in ‘Twin Peaks.’” They’d say, “Uh, you know that is cancelled, right?”, and I’d reply, “You never know…”

At the premiere, Lillard told me, “I can’t believe this happened for you.” He was obviously very pleased for himself because he had a great role and he knocked it out of the park. I thought it was one of the greatest things he had ever done. Every time I watch “The Return,” I always text him after I’ve finished his scenes and I always acknowledge how nuanced and wonderful his performance is. I know what it’s like to be in David’s world and to have to do something a little bit differently as an actor. Maybe you don’t know everything, but I think that there is also a really amazing opportunity to pivot and just commit to what you do know. You create your character and then allow yourself to be in his hands. I wasn’t onset for his scenes, but I just had the sense that he had done that, and I know that that’s what I did. I was just so happy that we were both in it.

It’s the magnum opus of Lynch’s career. I found it be immensely timely and therapeutic to watch during the first year of Trump’s presidency.

I felt that too. I looked forward to it every week. I love that we didn’t know when we were going to be on. I felt like the whole cast watched it without knowing when their scenes would turn up. Honestly, it’s very common for actors to just call in and ask for their scenes so they can throw them on their reel, but in this case, I just felt like everyone was watching. I watched all of it by myself, though I viewed a couple episodes with my mom, whom I watched the original with quite a bit. I did watch Part 13 with a group because Sabrina called me and said, “You might not want to be alone tonight,” and I thought, ‘Ah, I know what that means!’ That was great for me too because I met a bunch of cast members whom I had never met.

I loved that the show came out slowly like that because you could rewatch it during the week and mull it over. If you chose to, you could go to the global watercolor, which you couldn’t do when the first two seasons were aired. You could really do a deep dive talking to people, and I love that people were as excited as I was because I was over the moon, man. I would forget that I was in it most of the time. I would get emotional every time the theme song would come on and the cinematographer Peter Deming is such a beautiful talent.

Lynch might as well be talking about Dougie in this excerpt from the chapter on “Eraserhead” in Lynch on Lynch: “Henry is very sure that something is happening, but he doesn’t understand it at all. He watches things very, very carefully, because he’s trying to figure them out. He might study the corner of that pie container, just because it’s in his line of sight, and he might wonder why he sat where he did to have that be there like that. Everything is new. It might not be frightening to him, but it could be a key to something. Everything should be looked at. There could be clues in it.” This relationship between Dougie and Jack Nance’s character of Henry in “Eraserhead” is further accentuated by their similar pose in the elevator.

David and I talked about that moment, and the last time I watched “Eraserhead,” I noticed other things in the film that come back in “The Return.” As an actor, you have to do something over and over again, but it has to feel like the first time during each take, and it’s amazing when you learn about how many years they spent making “Eraserhead.” That sense of newness is something that I experienced working with David. His curiosity and that childlike way of looking at things afresh was really inspiring. I felt tuned into the fact that he had chosen me for specific reasons and believed that I was right for the role. He wanted me to explore, make unexpected choices, be spontaneous and present in the moment, welcome surprises and the unknown and be open to everything that is possible like he is.

There’s a uniformity to how he approached things on “Eraserhead” and “The Return.” It’s not that he hasn’t changed or that he hasn’t welcomed growth. It’s more that he has a dedication to a way of creating and it’s brilliant. It really does make room to dream. I almost did nothing else but think about Ray. I had “The Pink Room” on a loop in the car while driving around. I couldn’t believe my character’s name was Ray Monroe. How cool is that? I felt so trusted as well as connected to all these things that were familiar to me. I felt a real ownership right away. It was one of my greatest creative dreams to collaborate with David, and I felt a real freedom as an actor when I got onset because I knew he had picked me for the role.

You are not only in “Twin Peaks: The Return,” which is one of the most astonishing cinematic achievements of my lifetime, you are also in one of the greatest hours of television ever aired, Part 8.

We were all very tight-lipped throughout the show’s release, and I only know what happened with me in Part 8, but I remember that the day it aired, Peter Deming posted a picture of the Red Room on Instagram with the words, “Part 8, like no other.” For the rest of the day, I had butterflies, wondering whether this would be the one where Ray shoots Mr. C. When the episode began with the two of us in the car, it was the most conflated kind of experience in terms of me being a fan and in it. I had no idea how the scene was going to come across because I really let loose that night, and I was just slack-jawed. Then it cut to Nine Inch Nails performing, and I was like, “Oh my gosh, in the sea of the coolest of the coolest, this is the coolest! We just ratcheted cool one more time.” And then…it really started to happen, right? At the end of it, I just sat there in the dark and I remember thinking that it was my favorite Lynch movie that I had ever seen, and I was so glad that I was in it. I looked at my phone and it was blowing up. I remember my funniest text was from Nicole, and she was like, “Partner! What?!”

It meant so much to me as a student and a collaborator of David’s, as a lifelong fan of “Twin Peaks” and as somebody who had a huge affectionate connection for the mythology. To be in a night drive scene was part of my Lynch bucket list, and the episode was full of these great, eerie, sort of ominous silences. I did get to see it on the big screen when they screened the entirety of “The Return” over three days at MoMA. Seeing those six-hour chunks with people was really miraculous. The tired criticisms aimed at the show like, “Dougie takes too long,” just aren’t true, and this screening confirmed it. Seeing Part 8 with people was fantastic. You could hear audible gasps. I hadn’t really been reading too much about the show because I didn’t want to know what other people were thinking yet. I was digesting it myself, but my manager started sending me Part 8 articles almost right way, and I was like, “Maybe I’m not the only one who felt that way.” I can’t wait for my kids to see it.

It was so galvanizing to see Penderecki’s “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima” finally fused with the sort of imagery it was originally intended to evoke.

It’s really breathtaking. I always think that David is part of film history and film’s future at the same time. It felt like Penderecki slid that music right over to Lynch and was like, “You are the only one who can put a visual to this.” I don’t think there’s anyone else who could’ve done that.

The characters Gordon Cole refers to as the “dirty, bearded men in a room” feel somehow related to The Man Behind Winkie’s in “Mulholland Dr.” Lynch’s portrayal of LA feels closer to life than any other in how he portrays the city’s homeless occupants, most movingly in “Inland Empire.”

I think it harkens back to what we had been discussing about seeing characters on film that you might normally judge. Maybe you walk quickly by them because you’ve put them in some archetype that is easy for you to dismiss. I watched the recent restoration of “Inland Empire” upon its release, and those scenes on Hollywood Blvd with Naido, who is in “The Return,” really struck me too.

What makes the inclusion of “From the Head” at this year’s Lynch retrospective particularly special?

Well, I’m trying to not be too hyperbolic, but I don’t think that either I or “From the Head” would exist in the same way without David Lynch. His influence on me has been so multi-tiered. It’s been personal, it’s been artistic, it’s been spiritual and it’s been professional, and all of those things are interwoven. I couldn’t be more humbled or grateful for that, and I feel really proud to be brought up in the same sentence as him, honestly. As an artist, I really desire purity and I think that I felt fortified in that endeavor by my connection with David. One of my favorite things is to talk about film. I don’t always get to talk about my film, and I don’t always talk about David or “Twin Peaks” because I don’t want to be like Neil Armstrong going around every day saying, “I went to the moon, baby!” But it’s had such a profound resonance for me and I’m really grateful for your thoughtfulness. It means a lot to me.

“From the Head” screens in 35mm at 9:30pm on Wednesday, May 31st, at The Texas Theatre in Dallas with George Griffith in attendance as part of “David Lynch: A Complete Retrospective.” For tickets, click here, and you can find the full festival lineup here.