1.

"Truly Inconvenient Truths: 'The Island President' and 'Issue Doc' Aesthetics": An essential essay penned by Andrew Lapin at Oscilloscope.

“Jon Shenk’s 2011 documentary ‘The Island President’ is the climate change movie we need right now, and from a stylistic viewpoint, it’s the ‘issue doc’ other filmmakers should cherish. On the surface, it carries a similar structure to Guggenheim’s film, in that it gives us an intimate portrait of an idealistic politician trying to warn the world about the dangers of fossil fuel consumption. The difference is in its operatic tone and execution, and in the underlying, pervasive sense of futility. The titular island president lives on both a physical and figurative island, as he’s woefully overmatched against both the natural and human forces that will ultimately destroy his home. Our hero is Mohamed Nasheed, who, once upon a time, was president of the Maldives. While he was in power from 2008-12, Nasheed made climate change his top priority, due to the fact that his low-lying country of 26 atolls is literally being washed away by rising sea levels. (Research differs on whether the islands themselves can adapt to higher tides, but not on whether developed, industrialized land can survive. It can’t.) The genius of the film is that it’s not solely concerned with environmental alarmism. How Nasheed ascended to power, how he became a leading global voice from such a relatively tiny platform, how squabbling with much bigger countries over fossil fuels nearly broke him, and how he was eventually ousted from his position is the stuff of a great narrative arc. It’s the story Shenk embraces, via a mix of documentary techniques that keep the audience from growing too comfortable.”

"Amy S. Weber on 'A Girl Like Her'": At Indie Outlook, I chat with the writer/director about her powerful teen drama currently available on Netflix, iTunes and Amazon.

“When I was very young, I was bullied and abused by a classmate of mine. […] The boy got so angry with me that he threw me down face first onto the cement and damaged my four front teeth. When we moved a year later, I was determined that no one would ever pick on me again. I became a fighter, and I would only fight boys. I don’t know what overcame me. I was a pretty hyper kid and I had a lot of strength that most people couldn’t explain. I was very feared, and that reputation stayed with me up until junior high. During those years, I realized that I didn’t know if people really liked me or if they were just afraid of me and wanted me on their side. I had so much pain that I couldn’t talk about, and being a lesbian, I knew that I was different as well. All I was ever celebrated for was my athleticism in sports. I never really felt grounded in my own skin, so I wouldn’t allow people to see my vulnerable side. Although I wasn’t like Avery in how she targets one person to bully, it was known that if you messed with me, you would most likely get hurt. Bullying is obviously different nowadays because of social media, but the pain is still very much the same. This film was very healing for me on both sides. It has helped me reach out to people who I had hurt in the past—either by saying something mean to them or hitting them or just making them feel small. There’s been a couple of moments where I’ve been able to sit and hug those people and apologize to them. I’ve found that you tend to forget about the bullying you’ve committed, but the victims never forget it. I’ve had men in their 70’s see the film and tell me stories about getting bullied in their youth as if it happened yesterday. The film enabled me to forgive myself for the things that I did, and also forgive what happened to me as a kid.”

"The Original Underclass": The Atlantic's Alec MacGillis and ProPublica explore the history of poor white Americans.

“By the time the nation gained independence, the white underclass—its future dependents—was fully entrenched. This underclass could be found just about everywhere in the new country, but it was perhaps most conspicuous in North Carolina, where many whites who had been denied land in Virginia trickled into the area south of the Great Dismal Swamp, establishing what Isenberg calls ‘the first white trash colony.’ William Byrd II, the Virginia planter, described these swamp denizens as suffering from ‘distempers of laziness’ and ‘slothful in everything but getting children.’ North Carolina’s governor described his people as ‘the meanest, most rustic and squalid part of the species.’ Accounts of this underclass as ‘an anomalous new breed of human,’ as Isenberg puts it, proliferated as poor whites without property spread west and south across the country. These ‘crackers’ and ‘squatters’ were ‘no better than savages,’ with ‘children brought up in the Woods like brutes,’ wrote a Swiss-born colonel in the colonial army in 1759. In 1810, the ornithologist Alexander Wilson described the ‘grotesque log cabins’ where the lowly patriarch typically stood wearing a shirt ‘defiled and torn,’ his ‘face inlaid with dirt and soot.’ Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter came back from an 1817 excursion with her grandfather telling of that ‘half civiliz’d race who lived beyond the ridge.’ In 1830, the country even got its first ‘Cracker Dictionary’ to document the slang of poor whites.’”

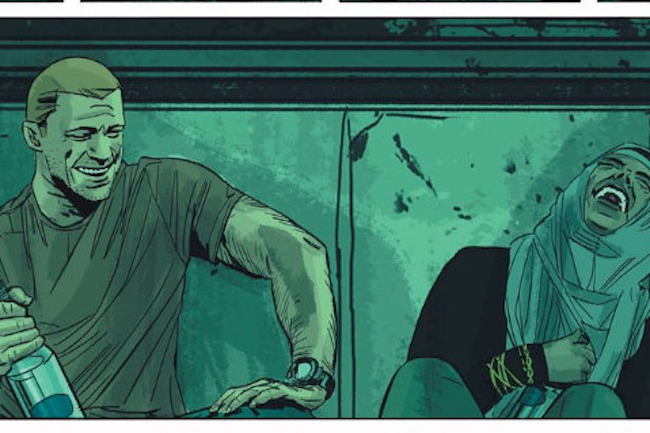

"The Best Retelling of the Iraq War Story Is a Comic Book": According to Vulture's Scott Beauchamp.

“What I’ve been looking for since I left the Army six or so years ago is a story about the war that provides both granular accuracy and a bird’s-eye perspective normally unavailable to me, an American who is confined in many ways to an American perspective, even (especially?) as a soldier. Iraq is, after all, more than just the name of a region where American military ambitions are exercised and foiled. Iraqi people were part of the war, too, and just as American history doesn’t begin with 9/11, the contemporary history of Iraq doesn’t begin as a blank slate with the American invasion. I always desired a story that would acknowledge and defy these artificial parameters in order to convey the complexity of the American invasion of Iraq. In essence, I was searching for an Iraq War version of War and Peace. I did not expect to find it in a comic book. Sheriff of Babylon, written by Tom King, illustrated and colored by Mitch Gerads, and published in July by DC imprint Vertigo, is, in my opinion, the most comprehensive war fiction of our generation. It’s a political story. It’s an unmasking of violence. It’s a noir mystery. It’s a complex rendering of an entire ecosystem of squalor, hope, and delusion. It’s also accessible and, almost as a bonus, very cool. If you put a John le Carré novel, season five of ‘The Wire,’ and Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s masterly nonfiction expose Imperial Life in the Emerald Cityinto a blender, what would come out would resemble Sheriff of Babylon.”

"Why 'Point Break' Still Delivers 25 Years On": As observed by filmmaker Stephen Cone ("The Wise Kids," "Henry Gamble's Birthday Party") at The Talkhouse.

“Midway through my young life re-viewings of ‘Point Break,’ sequences that had previously played to me as generic downtime for conventional rhythm’s sake, requisite scenes of lightness and romance, began to seem no less vital to the picture, nor less important to Bigelow, than the showboat action sequences. Whether it was the late-night swim with Tyler (Lori Petty), the twilight suburban foot-chase or the midday, sun-scorched sky dive, this was a film that was evoking nature and time in ways that would’ve made Terrence Malick or Sofia Coppola proud. In this sense, ‘Point Break’ has seemed to me, increasingly, to be one of the great Present Moment movies, such as ‘The New World’ and ‘Marie Antoinette,’ in which there movingly exists an ever-present half-awareness that this too shall pass. This is especially true in regards to the late Patrick Swayze’s performance, and not just in the posthumous, retrospective sense. Already 37 at the time, his truly great performance is one of deep melancholy, of an aging man’s attempted oneness with impermanence and the resulting loneliness incurred. It’s one of the most genuinely inspirational, achingly sad visual records we have of a once mighty hero, as devastating in its way as an Edison film of a small child in a garden, now a ghost.”

AnOther Magazine's Daisy Woodward unearths Gus Van Sant's candid polaroids of Hollywood's rising stars.

Last month's hugely enjoyable 30th anniversary panel for James Cameron's 1986 action masterpiece "Aliens" at the San Diego Comic-Con featured big laughs, lots of cherished memories and even a marriage proposal.

Matt Fagerholm is the former Literary Editor at RogerEbert.com and is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.