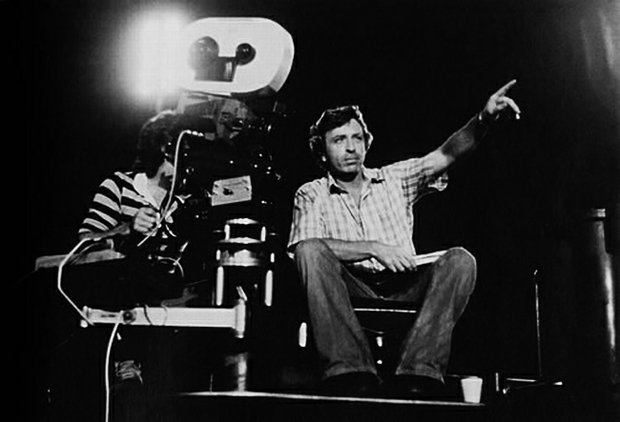

There's usually an element of social critique at the heart of American cult filmmaker Larry Cohen's films. Cohen started as a TV screenwriter and then began writing and directing exploitation gems like "Black Caesar," "It's Alive," "Q: The Winged Serpent," "The Stuff" and "God Told Me To." Many of these films hold up extremely well because, while they were often shot guerrilla-style due to budget limitations, they stem from personal outrage and political dissent. They come from a specific time and place, but don't really feel dated since their preoccupations are universal: institutionalized racism and the self-loathing it breeds; insidious, self-perpetuating commercialism; thriving opportunism amidst corrupt institutions; and a general tendency towards apathy. RogerEbert.com spoke with Cohen about his films on the occasion of New York's Quad Cinema weekend-long retrospective of his New York-set films, including the New York premiere of the early "Whisper" cut of "God Told Me To."

What was an average length of time for you to scout for locations for your New York films? I'm thinking especially of the scenes in Chinatown in "Q: The Winged Serpent," and the scenes in Harlem for "Black Caesar."

I never used a location that I didn't want. I never got a place I couldn't shoot. For "Q: The Winged Serpent," we used the Chrysler building. I had to go back five or six times, and they kept saying "No, no, no." I kept coming back, offering a little more money. And eventually, they agreed. I would have been very disappointed if we hadn't got the Chrysler building. It's the best-looking building in the city, and it's got all that bird stuff on the sides of it. I had to have it. It wasn't in the script though: it just says "a skyscraper." I didn't promise to deliver the Chrysler building. Other than that? In terms of scouting locations? Forget about it! We almost never scouted locations. I went some place, I saw it, I shot. That's it.

We went up to Harlem for "Black Caesar"; hadn't been there before. They had just shot a movie called "Across 110th Street" with Anthony Quinn ... Big production, trailers dressing rooms, equipment trucks, and everything filling up the streets. So when we came up there in a taxi cab, trying to shoot a movie, the crew were maybe six people. A bunch of gangsters from Harlem came over and said, "You can't shoot here unless you pay us. You have to have a pass for every street you shoot on." I thought to myself, "I have no budget to pay for this kind of thing." So I said "Hey, you guys: do any of you know how to act? You guys would be great in the movie playing the gangsters." Next thing I knew, I owned Harlem. We had everything we needed. And later on, when the picture opened at the Cinerama Theatre on Broadway, these gangsters were outside the theater signing autographs. Because their likeness was used in the posters as well. When we went back to do "Hell Up in Harlem," it was our town. The teamsters and the unions that we weren't involved with were reluctant to follow us up to Harlem. When you passed 125th Street, they turned back. They didn't want to deal with Harlem. In those days, those unions didn't hire black people. Harlem was enemy territory. But once I got up there, nobody bothered me. We owned the town. I felt that way about New York City anyway. Anywhere we went, we owned the town.

We shot this one sequence in "Black Caesar" at 57th Street and 5th Avenue, right in front of Trump Tower. And every time I see Trump Tower, I laugh and say, "We wouldn't have a chance of getting within a half mile of that joint if we were making the movie today." But in those days, we just closed down the street. The cameraman showed up the first day, and Merv Block's office—he owned an advertising agency in those days—was where we stored the equipment. The cameraman, James Signorelli—who went on to film all the filmed sequences for "Saturday Night Live"—was a young guy. But he looked older because he had a beard and a pony tail. Without it, he'd have looked 16 years old. He shows up and says "Where's the crew?"

"There is no crew! You're the crew!"

"Well, where's the equipment?"

"There's the equipment in the hallway."

And that was it. We went down to 57th Street and 5th Avenue. I had one of my people, [associate producer] Jim Dixon, dressed up as a police officer. We closed the street down without any permission from anybody. And we shot this scene where Fred Williamson gets shot. He's lying in the street. We had hidden cameras, and shot it various ways. Then we came back a half hour later, and changed positions. Then we went inside a nearby building and shot it from a window. And every time we shot it, people on the street really thought that this guy had been shot. They went to his aid, helping him to his feet. We had all this interaction with real, live people in the midst of this sequence. You could never do that today. You can't run around New York with guns in hand. You can't fire machine guns off the top of the Chrysler building either [as David Carradine does in "Q: The Winged Serpent"].

Doubling back for a moment: "Black Caesar" remains one of your best films partly, because of how rich Tommy Gibbs, Fred Williamson's character is, especially in the scene where his estranged dad breaks down, and explains that he was only 20 years old when he entered the military service and abandoned Tommy. Where does that scene come from?

I don't know. I just thought it would be a good idea to have a personal relationship between the two characters. We also gave him a relationship with his mother, who's a maid for rich people. He buys her boss' apartment, where his mother worked for her whole life. And now, after he buys it, it's her apartment; he gave it to her. But she doesn't want it. She's uncomfortable with it. And the father is a father who's abandoned his family. That dynamic has become prevalent in both white and black communities. In the sequel, "Hell Up in Harlem," the father returns, helps the son, the son takes him into the business, he becomes a gangster himself, and he becomes a rival gang leader. And he ends up getting killed. So the second picture is a true continuation of the first film's story.

In "Black Caesar," Tommy's mom has that great line: "Jewish folk ain't even allowed in here!" You've said that you weren't really bothered or questioned when you filmed in Harlem, but what had been your personal experiences of racism in New York when you made "Black Caesar?"

I went to college at City College, which is located in the middle of Harlem. So I was up there all the time. Relationships between white people and black people were quite different in those days. There was a lot of turmoil in the community if you saw a white man with a black girl, or a black man with a white girl. There was a tremendous amount of racism. When I was in the Army, I was in Washington, D.C., which is only an hour away. But I couldn't believe that one hour out of New York, there was such pervasive racism. The use of the "n" word everywhere, white people being intolerant of black people ... it was much worse in Washington, D.C. than in New York. Washington, D.C. was like a little Southern town, and it was quite unpleasant, I thought.

Then I made a picture called "Bone."

Which is great.

That was my debut picture. And that had everything to do with racism in 1972. It's still relevant today. It really deals with the essence of racism, and the projection of white guilt and white violence on black people. Black people take the rap for white people's violence. Almost all of the killing going on in the 20th century has been perpetrated by white people, usually against people who are not white. Talk about what happened in Vietnam ... everybody looks the other way, and never learns the lessons of the past, so we relive them all over again.

I thought of "Black Caesar" and "Bone" when I watched "Get Out" and "Luke Cage" because of a line of dialogue from "Black Caesar" that Fred Williamson delivers: "Everybody's a liberal. Get with it!" Have you seen "Get Out," or "Luke Cage," or anything lately that's struck a chord with regard to race relations?

If you watch the news, you'd think race relations were worse today than they were in the 1970s. They haven't burned down the town lately, but there is still a tremendous amount of anger and resentment. There's the white police officer in "Black Caesar" who behaves very badly to the black characters in the film. In that film, they use a black teenage boy to deliver bribes to the cops. Turned out later on that that was exactly what was going on: they were using kids to deliver the bribe money to cops. I made it up, but it was true.

Did any African-American viewers object or comment to you about the fact that you essentially made Tommy Gibbs question his motives or doubt himself? You've even said in an earlier interview that ["Black Caesar"] subverts blaxploitation conventions by making Tommy incapable of having a working relationships with his girlfriend and his parents. The ending, where Gibbs dies, wasn't an issue, but how did African American viewers interpret the self-doubt and maybe even self-loathing that the character exhibits throughout the film's second half?

No, the audience responded to that picture immediately. As soon as I took off the last scene, which audiences didn't like at the preview screening in Hollywood. I'm talking about the scene where a bunch of teenagers beat Fred Williamson character to death because they think he's an itinerant, and they want to steal his wrist-watch. The audience did not want to see him killed. But the scene really was apropos because his character starts out as a teenager killing somebody, and then at the end, it's black teenagers killing him. Still, some of the people at the screening—particularly black women—were screaming at me in the lobby: "Black people don't do that to each other!" But of course that's not true, since the greatest percentage of violence against black people is committed by black people. That's the truth. It's unpleasant to say, but when they say "black lives matter," it not only applies to the police, but applies to the community because blacks kill each other all the time. Because of gang shootings, children and women get killed in the crossfire. That's one of the problems today: in order to survive in the ghetto, you have to be part of some organization.

So I cut that last scene off after the preview. Had to go to the three theaters in New York where the picture was playing. I introduced myself to the projectionists, cut off the last scene of the picture, spliced on the previous scenes, and added the end titles. There were lines around the block. It was such a big hit, that they started to put in shows at 3am. Then they started showing the film again at 8am. And they raised the prices by a dollar. It was the middle of February, and people waited in line for the next show. It was freezing cold. I drove down with my wife, and we thought, "This is great, this is the way it's always going to be." Unfortunately, in the movie business, that doesn't always happen. But this particular case was such a big success that we almost immediately made the sequel right afterwards.

One of the recurring themes in your films is this notion of guilt and responsibility which is in "Bone," "Black Caesar," "God Told Me To" and "Original Gangstas." In fact, in a broader sense, a lot of your films are about who is responsible for culture, and where it comes from. In light of that, I've always wondered why you haven't taken a swing at gentrification in your films, and about the people who actively erase the city's history for profit's sake. Do you miss the old Times Square, for example?

I don't mind Times Square. I like all the automated billboards; I kinda get a kick out of it. And I don't know, just because it was dirty and sleazy before—a lot of prostitutes wandering around—doesn't mean we have anything to lament. So what?

As for guilt and responsibility: there's still a gang mentality at play that affects gang culture today in music, clothes ... white culture has also always idealized gangsters, whether it's Don Corleone or "Little Caesar" or James Cagney. These have been fodder for movies for decades. How many times have they made a Jesse James movie, or a Billy the Kid movie? C'mon, so many times you can't count 'em. So the fact that the black gangster has become such a mythological figure ... and white kids are now imitating black kids now, with their hats turned around, and such. And the music. There's an awful lot of anti-cop stuff in the music, in the lyrics, stuff that would really indicate that it would be a great thing to kill a cop. And naturally when they say they're going to kill a cop, they mean a white cop. So this is bad stuff from any point-of-view. It's a whole side that you have to get out of if you're going to have a peaceful relationship with people.

I don't mind that they cleaned up New York a bit. In fact, it probably needs more cleaning up. I can't walk down the sidewalk without tripping over cracks in the sidewalk, and all the dirt in the gutter. I just came from Chicago. There's an amazing difference. Chicago is clean. New York is just filthy. Why Chicago should be that much better in terms of the way streets are kept ... I mean, every Chicago street corner has got flowers growing. And the sidewalks you can walk on? What's the matter with this town? People used to see New York as a location for shooting people on the street, fights, and violence, stuff like that. That's what it was good for. But I don't think it's a bad idea to clean up the place.

Switching gears for a moment to another one of your New York films: "God Told Me To." I was trying to find more information on the "Whisper" cut of "God Told Me To," but the only thing I could find was in a 1983 Sight and Sound interview by Tony Williams, where the film is referred to as "Demon." What are some of the key differences between the "Whisper" cut and the one that was since released theatrically?

The "Whisper" cut precedes the other cuts. This was when [legendary composer] Bernard Herrmann was still alive, and was going to do the film's music for me. We'd done a rough cut of the picture to show people, not theatrically, but just internally. And we used sections of Bernard Herrmann's music from other movies, like "North by Northwest," "Marnie," "Vertigo" ... stuff like that. And that's the track that's on this particular cut. It was never intended for theatrical distribution. And it lacks some of the special effects sequences that we later added at Pinewood Studios in England. But you know something? This picture's better off without special effects. It's better off without cut-aways to the special effects. The only scene that's a little bit shorter is the massacre at the St. Patrick's Day Parade, where Andy Kaufman ... all his stuff remains in it. But after we shot all the New York scenes for that sequences in New York, we re-staged the parade in Los Angeles. We inter-cut that with the New York stuff, and made the sequence more elaborate. But you know something? Doesn't matter. The fact that it's shorter doesn't matter. And over all, I happen to like this cut of the picture better. I think I was egged on by people who told me that if we put in special effects shots, we would make the picture more commercial. But I was perfectly happy with this version. So I urge anybody who likes the movie to come and see this cut. It's a little different, and there was about four or five scenes that were taken out of this version, and that wouldn't make the final version.

I revisited another one of your New York movies, "The Stuff," and it made me wonder what you thought of Bloomberg's soda ban.

There's so much stuff that's going around that's poisonous, or just bad for people—and the people that sell the stuff gets away with it. Maybe somebody gets prosecuted once in a while, somebody gets a fine. But people putting stuff on the market that has killed people! And nobody goes to jail. Maybe there's a million dollar fine. But that's the shame of it. People peddling this stuff should go to jail, not some poor guy trying to feed his family by robbing a grocery store. Why should he go to jail for ten years, and some guy who steals billions of dollars go to jail for two years, and pay a fine. It's ludicrous, and shameful. The rich—the real crooks—should get longer sentences than poor people. Because they don't need to steal. They get the most expensive lawyers, they pull strings, and they get out of it. At the end of "The Stuff," if you remember, they just re-release the poisonous food under a different name.

"The Taste!"

Yeah, right. And that's the truth.

Your films concern several prevalent social issues. What's the one issue that you can't stop thinking about?

I'm always a little bit leery about the demonization of some group that becomes the enemy, and we have to go kill them all. And a couple years later, we're their best friends. I lived through the end of WWII. There was such anti-Japanese propaganda during the war: how many Chinese they butchered, and raped, and murdered. And a couple years later, we're driving their cars, watching their TV sets, and eating their food in restaurants. I mean, come on! We're going to do the same thing all over again. There's no reason we can't imagine that the Taliban and Al Qaeda will be our friends within 25 years. What, do we have to kill three million of them first?

And usually, when we destroy people's homes, we have to rebuild their country for them. When you go over to their country, they have better facilities—better streets, better subways than we do. They lost the war, but if you look at the two countries, you'd assume we lost the war, because their situation is so much nicer than ours. Look at our bridges, and elevated trains: they're all rusty, and collapsing. They say that the tunnel to New Jersey has to be rebuilt, that it's going to cave in. And you go to a foreign country, like Germany or Japan, and everything is modern, and clean. What's going on here? All those poor [soldiers] are still dead and buried. What's it all about? Why do we keep getting into the same cycle of creating enemies, and then we're all friends again years later? Come on, why can't we get to be friends without killing each other? It would be nice, wouldn't it?

Simon Abrams is a native New Yorker and freelance film critic whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.