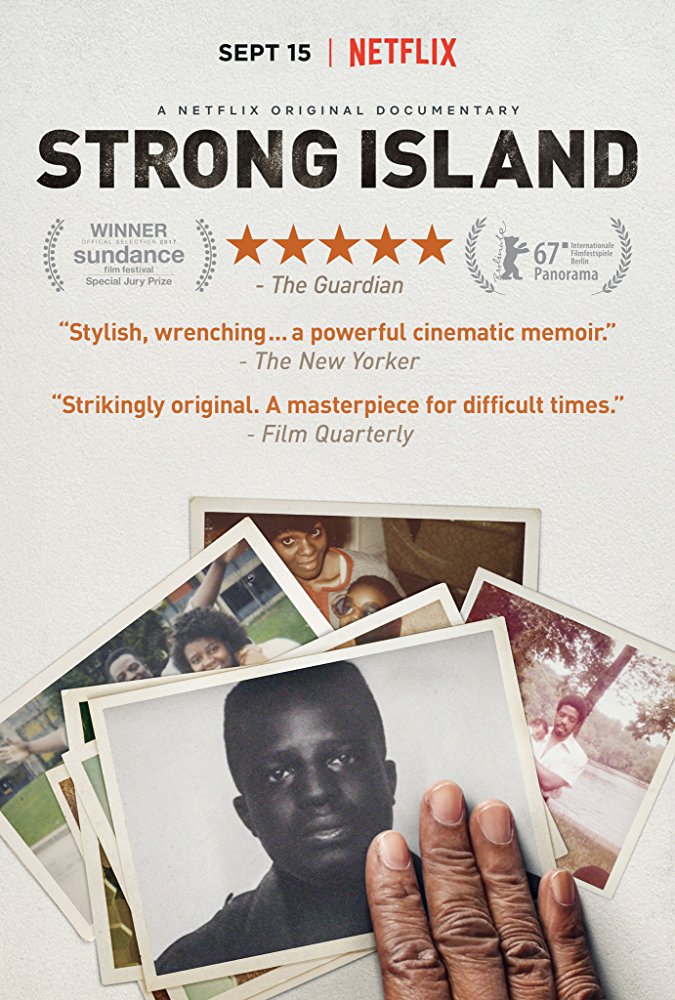

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. "Strong Island" is currently streaming on Netflix, and available for free on YouTube. #BlackLivesMatter.

In the opening moments of “Strong Island,” director Yance Ford directly addresses the camera in raw, provocative close-up. The painful, intimate story of grief to follow focuses on the life and sudden death of Yance’s older brother William—murdered in cold blood in 1992 at the age of 24. William, unarmed and black, was shot by a white mechanic after a disagreement ensued. A Grand Jury never even bothered to charge William’s murderer with a crime. Charting the decline of the Ford family after William’s untimely death, “Strong Island” is an exploration of race, class, and a broken criminal justice system in a national still convulsed by hate crimes. Back at the beginning of this year, when President Trump had just been sworn into office and Berlinale Film Festival was in full swing, I sat down with Yance Ford to talk about his excellent documentary film.

It took you 10 years to make “Strong Island.” Can you tell me a bit about that?

In 2006, I began development on the film, writing about it and talking to different filmmaker friends about how I might approach making a film. At the end of that year, I wrote my first development grant—then we were shooting. I did my first interview with my mother in 2008. And then from there, we found my DP. We didn’t take off like a shot, but because I had such specific rules for shooting the film—the formalism is very deliberate and was part of the visual signature of the piece from the beginning. You know, we have over 500 hours of footage because I also asked that our shots be at least one minute in length. Because I like to see what’s going on in the frame.

So my DP and I worked very closely together, often just the two of us when it was material of my mother or at the house. And then when the interviews happened, it was the same. Center frame, put a chair there, and place them in a place of authority, for all of the characters. The treatment of my character is deliberately different, but we had a really meticulous process that resulted in maximum flexibility in the edit. So I’m glad we took as much time as we did to shoot, because without some of the things that happened by both design and by accident, we would be missing some of the most brilliant moments in the movie.

The editing in the film is so deliberate and seamless. How involved were you in editing and what was your approach in terms of structuring the film?

One of the things that’s important to know is that we were at a cut that was 2 hours and 45 minutes long. Then in April 2014, after about two years of relentless killings of unarmed black people, I took a step back. I needed to ask myself, ‘Who is this film for and why am I making it?’ And is this exactly the film I want to make? The answer to that question was no, this isn’t exactly the film I want to make. And so, Jocelyn Barnes, who’s been my exec producer for a few years, I asked her to come on as producer, and we completely reconceived the film, we moved the edit to Denmark, and we started over. [...] We also made a deliberate decision to reveal William and the events of the death—and the events on the night he was shot—we wanted to reveal those things in layers. So at every moment, there was a new bit of information given to the audience. A new confrontation. A new question, encounter.

[...] The edit was as carefully constructed as the film was shot, and the formalism allowed us to put together this rubix cube and have each turn of the film be another pass at solving the puzzle. Then when you finally get to the end of the film, and there’s that question—‘how do you measure the distance of reasonable fear?’ It’s not a rhetorical question. It’s an actual question, and the final statement my character makes to the audience. So it’s the one we hope our audiences will grapple with on a real level.

You look at your brother’s murder from almost every conceivable angle. It seemed as though the questions about the justice system were very clear-eyed and incisive, whilst it also was naturally a very emotional piece. I wondered how you were able to—not remove yourself obviously—but how you were able to return to such a traumatic thing with a philosophical perspective?

The ten-year production and edit really allowed us—well, me—to cycle through a few realizations as a filmmaker. For example, it allowed me to understand the justice system and how Mark Riley got away with killing my brother. The explanation for that is actually quite simple. It was simple in 1992, and it is now: it’s relatively easy to take a black life and not be punished for it.

So, at one point there was all this other stuff—but it was like, no, what’s the most essential thing about this experience? The essential thing was the ease with which you can get away with killing someone if you’re white and the victim is black. What is essential is that black victims of crime almost always need to be the perpetrators of their own deaths. You’re the victim of a crime, but somehow you get turned into the criminal.

So the ten years allowed us to slough off all the unnecessary analysis—of something that’s simple—and get to the other part of the story. The other part of the story is: what is it like to be on the other side of this? What is it like to be my parents, having survived the Jim Crow South, gotten out of it [...] Most black families went from the South to the city. My family went from the south to the city to the suburbs, because they wanted their children to have the realization of the suburban lifestyle. What does it mean that that doesn’t actually protect you? There’s a realization that in America that class does not protect you, that status does not protect you, and that the law does not protect you. And so these are things we were able to crystallize over the amount of time we made the film.

That allowed us to keep things simple—even when you see David Green and his explanation of the Grand Jury process, we just provide the information you need. Because it’s actually very simple. The standard for a Grand Jury was that maybe someone committed a crime. That’s all.

Which is what makes it so shocking that they didn’t indict.

Right. And they were like, no, this wasn’t a crime. If I had done this, of course it would be a crime - I would be in jail. So being able to strip everything down to its essence allowed us to keep the line of inquiry about the case very clear. Also to engage with that second line of inquiry, which had been clouded over with all these other questions, and really focus on the story of the family. And the long tale of my brother’s murder and how it really took out my family one member at a time. My father was the first person to suffer a catastrophic physical event, after William died, and that is very in line with statistics about fathers who lose their children to violent crime. My mother succumbed to a similar traumatic brain event 20 years later. My sister and I...we’ve both struggled and are both more at peace now with the lives that we could have lived. The people that we could have been, if not for my brother’s murder.

In the film, you do address race, but you also choose to keep the story narrow and focused to as things began to happen in 2014, as you said - did you ever consider explicitly addressing some of the contemporary events that were happening? I do think it shows how the personal is deeply political. But I’m curious about how you made those decisions?

I had always thought of the film—and shot it—as more intimate than personal. For example, from the framing of my mother to the non-synced sound of some of her dialogue, it’s meant to give you the impression that you’re eavesdropping on an internal thought process. It was meant to be told from the inside out, rather than as a viewer.

The direct address was always part of how we intended to build the film. In terms of race or making race more obvious, I think it’s simply obvious through the optics of the film. For example, the photographs in the film. I’m not sure how many photographs of African-Americans get seen in documentaries, and we present them for what they are - which is—everyone in the audience has a shoebox of pictures that look like this. But the thing about race that clicked for me—and it was a real breaking point—in 2014, I forget exactly when—I had been treating my brother’s death, unconsciously, as something that had only happened to my family. And I realized I needed to re-contextualise his death as a point - you can see, in the film, the story of my grandfather being allowed to die in the colored waiting room of a hospital in South Carolina. And you know, it expresses itself again in the death of my brother. And that continued —continues—to express itself, on a long line of racial violence in the United States. Once I was able to say, ‘no, this is not unique to us’ [...] I remind audiences that I’m in the fortunate position to make a film about my family. But there are so many families to whom this story is personal and real.

And your direct address to the camera, I know you said you at one point weren’t going to include it …

At one point, when I first started making the film, I had a list of ten rules, and most of them were aesthetic. They were about shooting absence, longing, loss, empty spaces, love, silence. One of the rules is I would never be on camera, and we’d only ever use my voice in non-sync sound. When we started shooting those interviews, and I had never imagined that we would use them. But the direct address to the audience was so effective. I wanted to achieve those raw, in-the-moment, sometimes combative, difficult, challenging, introspective moments. We put a wall of sound blankets between me and the crew, and that black void becomes the space in which my character does a few things. She wrestles with her own guilt, my character directly addresses the audience, challenges the audience from that space. And I wanted that conversation to be between my mother and the audience, my sister and the audience. but the challenging content comes most from my character. And I think the direct address was the best way to do that.

Also, my mother is so charismatic onscreen. You know, she’s—

She’s the backbone of the whole film.

She is. She’s so eloquent about her own experiences, and able to put into words what most people might struggle to. And my character—I had an obligation to my mother, my sister, and my brother’s friends—to take the same risk as they did. Which was honest, unvarnished, unedited responses to questions. And that’s really the function of the direct address. I think that making eye contact with the audience is really important.

The result is that it’s not a film easily put to one side or forgotten.

No, we really wanted to make something that would stay with people. To ask a question that would hopefully inspire people to question their own assumptions about how their fear is formed, and if their fear is racialized. Because if you can ask yourself those questions, you can look at wherever you are, you can look at your own criminal justice system and see if its 'color blind,' which as a notion is insane.

One of the hardest parts of the film is when your mother says she believes she failed as a parent to keep her child safe. Do you believe that she ever changed her point of view about that?

I think that she recognized the failure of the criminal justice system. I don’t know she was ever able to shed her own feelings of guilt, Which I think is very common in families even when perpetrators are punished. If only I had done this, or done that. She never was able to fully set aside that if she had done something differently, that she could have prevented my brother’s death. The truth of course is that the only person who could have prevented my brother’s death was Mark Riley. He could have made the choice not to shoot my brother. But my mother always lived with this often crippling guilt.

My mother is such a fantastic person, and she was so wounded by the failure of the criminal justice system. It was something that she held a really deep faith in. She was even saying to herself at my brother’s funeral, 'just wait until we get to court.' So when it failed her and the rest of my family, it’s like having the rug pulled from under you. Where do you from there? Where you go is inward. And what happens is there’s an implosion. Lots of people have asked me here about closure and catharsis. And I’ve explained that it’s neither of those two things. It’s a process.

What was it like sharing the film, during the first screenings?

The first few times—we premiered it at Sundance, and Berlinale is actually only our second time out. It was nerve-wracking. Not only did we premiere it in the middle of a blizzard, we premiered in front of a packed house. It was almost a—not an out-of-body experience, but I was really nervous. Not nervous about the film but because I was in the position of spokesperson for the first time.

And of course your film premiered at Sundance during the week of Trump’s inauguration.

Thankfully, they programmed the film to screen just after the inauguration. And you know, I’m among a group of Americans who are not surprised by the election of Donald Trump. Many people who were surprised by it - friends and colleagues of mine—they tend not to be people of color. All of my friends in the community who are not surprised are POC. So it’s sort of like, what his election revealed is this schism in life experience. Yeah, the Klan is still around. Yeah, Neo-Nazis are terrorizing people still. Yeah, some white people are really resentful of the demographic shift in the United States. It’s like—why is this a surprise to you?

Going ahead, for you as a filmmaker, what do you feel like your role is vis-a-vis current American politics and the Trump administration?

I think in the immediate future, my role is to continue showing Strong Island, but also to push the conversation—to really push people to engage with the issues brought up in "Strong Island." The killing of unarmed people of color will continue, and I think my primary role as someone who’s lived with this for 25 years—because it’s not so fresh for me—is to stand up and say, ‘OK, we’ve heard this story before. If it sounds familiar, it’s because it was used with Emmett Till. With my brother. With Rodney King. The dangerous out of place black person’ In America, the very simple thing of thinking you can be angry and black at the same time can be fatal. White people get to do that all of the time. They get to engage in bad behavior, even felonious behavior, but they rarely wind up in jail. But as a black person, losing your temper can cost you your life. Or insisting on your rights can cost you your life.

So right now for me, my role with this film is to go out and—if the Trump administration start talking about a ‘law and order’ society—we know from Nixon what that means—my role is to say, remember history. It’s the only way that we’re going to survive the next four years, is if we take our lessons for history and apply them on a daily basis. We have to say: this is not new, this is how it was successfully challenged and defeated in the past, and it can be done again.