I have long had trouble enjoying live sporting events, concerts, and stage shows for three reasons. First, I would tire from watching the show from one single angle. Conditioned by movies, I need the variety of angles, the intimacy of close-ups and the sweep of tracking shots. Second, live events will never have the polish of a polished movie. And, third, (more applicable to large stage shows) the dialogue is always too enunciated and thus distant, even when it is "realistic."

I have long had trouble enjoying live sporting events, concerts, and stage shows for three reasons. First, I would tire from watching the show from one single angle. Conditioned by movies, I need the variety of angles, the intimacy of close-ups and the sweep of tracking shots. Second, live events will never have the polish of a polished movie. And, third, (more applicable to large stage shows) the dialogue is always too enunciated and thus distant, even when it is "realistic."

But James Foley's film, "Glengarry Glen Ross" (1992) is a precise, intimate, intense movie that tops its Tony award-winning play. Its all-star actors recite David Mamet dialogue, and the film's editing (Howard E. Smith) further enhances these perfect conversations into rhythms and palpitations. Despite its pulsating pessimism, the film is a joy to watch.

The atmosphere alone captures us. We enter a world without women. The off-screen women are sick daughters, domineering wives, and sexual fodder. It is a world of pathetic chauvinists dressed in power ties and F-words, dreaming of success, yet succeeding in nothing. They drink generic coffee in a generic office. They hide from themselves in a bland Chinese restaurant, and empower their miserable selves by peppering each other with abuse. You would not let these men near your children, but you might have voted for them in the last election. That is the feel of this movie: in most every scene, these feeble men beg for our support against a backdrop that is consistently a palette of red, white, and blue.

These are men who have graduated from the world of knives and vacuums into real estate sales; or perhaps they have flunked into it. We meet Alec Baldwin's Blake, who probably stares in the mirror, repeats his name to himself, and embellishes stories of his conquests. At the shallow end of the office is Jack Lemmon's exhausted Sheldon Levene, who was once known as "The Machine," but is now reduced to "Shelley." In between are the very successful, refined, conniving Richard Roma (Al Pacino), the testosteroned, temper-prone Dave Moss (Ed Harris), and George Aaronow (Alan Arkin) whose best hope for life is life as a sidekick. Managing the crew from his hermetically sealed den is the cynical zookeeper, Williamson (Kevin Spacey).

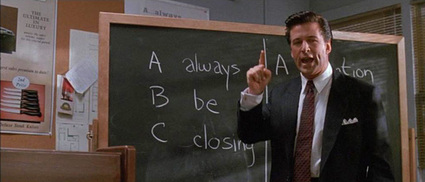

The salesmen work in a dead-end office with dead-end leads, and Blake has just given them an ultimatum: succeed in the new competition or get fired. There are two prizes (a Cadillac and a set of steak knives), with third place being termination. Roma will surely win first place. Doing the math: the other three are competing for the knives.

It follows, then, that we have two main storylines. One the hand, Roma has his own distinct thread, involving a sale to a tender, admiring man Lingk (Jonathan Pryce). Roma performs deliberately in each step, though he is more of a hunter with his sites focused on a deer, seeking to carefully introduce and close a deal. Later, he cuts loose trying to hurriedly salvage the unraveling deal. In the other subplot, one of the three competing salesmen carefully tries to lure a colleague into a scheme of revenge against their employer. In both threads, we realize that this movie is a story of predators and prey in a jungle, gnawing for the high post on the food chain. These are not dignified men in suits. Rather, they are animals locked and beaten in a cage, looking for the way out. And, like their characters, the storylines do not merge, as much as they claw through each other.

This is such a great film that I could reveal all the key plot points, and you would still find the film fresh and thoroughly satisfying. Each actor's every syllable and gesture is so meticulously crafted that acting alone would carry this film. Juan Ruiz Anchía's cold cinematography captures an art direction featuring detailed, yet empty offices, homes, restaurants, and cars. Every scene seems to be empty. And, James Newton Howard's jazzy soundtrack makes us feel like we are watching the film in a smoky night club, underneath the speeding elevated train. And, of course, we have David Mamet's classic writing, delivering an outstanding story, further ornamented with that lyrical Mamet dialogue. I certainly long for a return of the biting, sinister Mamet of Heist, House of Games, and Homicide, away from these apparent policy papers he has been publishing lately. In this case, it is truly biting and sinister that in this film we invest ourselves so thoroughly in such despicable losers.

Nevertheless, this film is so carefully synthesized that the real star of this collaboration is director James Foley. There are many great plays that provide more wonderful experiences than many great movies, but I doubt any play can top a film of this caliber.

Omer M. Mozaffar teaches at Loyola University Chicago, where he is the Muslim Chaplain, teaching courses in Theology and Literature. He has given thousands of talks on Islam since 9/11. He is also a Hollywood Technical Consultant for productions on matters related to Islam, Arabs, South Asians.