"Pearl Jam Twenty" is available On Demand (check your satellite or cable listings) and premieres on the PBS series "American Masters" at 9 p. m. (ET/PT), Oct. 21. It will be released on Blu-ray and DVD Oct. 25. For additional viewing, the grunge documentary "Hype!" is available on Netflix (DVD only).

by Jeff Shannon

Here in Seattle, we think of Cameron Crowe as an honorary native. When he married Nancy Wilson in 1986, he married into local rock royalty: Nancy and her sister, Ann, are the pioneering queens of rock in Heart, the phenomenally successful and still-touring Seattle-based band that is presently nominated for induction into the Rock 'n Roll Hall of Fame. It wasn't long before Crowe became a kind of de facto ambassador of Seattle-based rock.

At the time, the rest of the world still knew Crowe as the rock-journalist wunderkind who started writing for Rolling Stone at age 15 (an experience Crowe would later dramatize in "Almost Famous") and the author-turned-screenwriter of Amy Heckerling's 1982 high-school classic "Fast Times at Ridgemont High." You could reasonably speculate that the seeds of the Crowe/Wilson romance were planted in "Fast Times": Nancy Wilson makes a cameo appearance in the film as "Beautiful Girl in Car," catching Judge Reinhold's character in yet another moment of humiliating embarrassment. One can imagine Crowe thinking "I'm gonna marry that girl." When he actually did, countless male Heart fans turned green with envy.

(By sheer happenstance, I made a friendly connection with Crowe three years before we actually met. Shortly after the newlywed Crowe moved to the Eastside Seattle suburb of Woodinville, he and Nancy placed a mobile home on their rural property to accommodate visits from Wilson's mother. At the time, my father was running a mortgage business specializing in mobile/land sales in Snohomish County, and he closed their deal. When my dad informed Crowe that I was a Seattle film critic and an admirer of his, Crowe sent me a signed copy of Fast Times at Ridgemont High to my dad's office. It was a completely unsolicited gesture of kindness, and a pleasant precursor to later encounters.)

Synchronicity was working in Crowe's favor when he moved here: The Seattle indie-rock scene was aggressively brewing that potent elixir called grunge, and before long Crowe was in the thick of it, growing familiar with the bands that would soon turn the world's attention to the emerging "Seattle Sound." In 1991, Nirvana's "Nevermind" turned grunge into an explosive global phenomenon, and Crowe -- by now a mainstay on the grunge scene - was riding high on the success of his 1989 directorial debut, "Say Anything...."

Some of that synchronicity rubbed off on me: As a freelancer for The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, I interviewed Crowe and Wilson in Seattle just before "Say Anything..." was released to widespread critical acclaim (Nancy provided additional music to the film's celebrated soundtrack), and that set the stage for my visits to the set of Crowe's much-anticipated follow-up film, 1992's "Singles," filmed in Seattle at the height of the grunge explosion.

By the time Crowe was in pre-production on "Singles" in 1991, another band had joined Nirvana and Soundgarden as front-runners on the grunge scene. They'd played a few gigs as Mookie Blaylock in late 1990 (named after a then-dominant NBA all-star), but trademark legalities forced them to change their name. Thus Pearl Jam was born, named (according to newly-hired singer Eddie Vedder) after a peyote-laced jam recipe created by Vedder's great-grandmother Pearl.

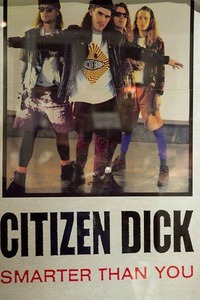

Ironically, Crowe's love affair with Pearl Jam has now lasted longer than his marriage (he and Wilson parted amicably late last year). Two decades have passed since Crowe cast Vedder and bandmates Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard as Matt Dillon's fictional "Citizen Dick" bandmates in "Singles." Now Crowe has crafted "Pearl Jam Twenty" as a performance-heavy documentary valentine, celebrating 20 years of Pearl Jam's evolution as one of the greatest bands in the history of rock. By Crowe's own admission, it's a film made primarily for fans by a fan, but "PJ20" conveys the universal appeal of grunge as a regional music that allowed little guys to dream big.

Grunge, in Crowe's eloquent estimation, was "music from guys who stayed indoors a lot," (due to Seattle's notoriously inclement weather), and listened to everything. "It all got cuisinarted together," says Crowe in his sparse narration, "into this majestic mix of great, melodic hard rock."

With the possible exception of Crowe, nobody enjoyed, appreciated, and took pride in the global explosion of grunge more than the native Seattleites who experienced its subcultural birth and growth throughout the 1980s. Before grunge belonged to everyone else, it belonged to us. Many Seattleites still feel a protective pride of ownership: A quarter-century after it began to define itself -- and 20 years after the release of Nirvana's "Nevermind" -- grunge is still our music. We just allowed the rest of the world to listen in.

As a rock fan focused on a somewhat stronger passion for movies, I wasn't a firsthand witness to the birth of grunge. Aside from occasional forays into Seattle's alt-rock nightlife, I was more of a listener than a club-goer, so the majority of my grunge education came from The Rocket, Seattle's late, great alt-rock biweekly (1979-2000), and Sub-Pop, the still-thriving Seattle indie-label that put most of the best-known grunge bands on vinyl, cassette and CD. While Crowe was club-hopping to see and hear grunge as it continued to define itself, I was attending film screenings four nights per week or more (for business and pleasure), mostly aware of local bands like Soundgarden and Pearl Jam from write-ups in The Rocket. Alas, a live-music hipster I was not.

As luck would have it, however, my first encounter with Pearl Jam occurred on the set of "Singles" in April 1991. The production had leased a vacant warehouse on Elliott Avenue, just up the street from the offices of the Seattle P-I, and I dropped in to visit on a day when Crowe was shooting the third-act reconciliation scene between young Seattle lovers played by Campbell Scott and Kyra Sedgwick. The apartment set and adjacent hallway belonging to Scott's character was built on an elevated platform, and some crewmembers handily lifted me and my wheelchair up to a viewing area near the set.

There, on a small sofa just out of camera range, sat four guys I knew only from photos, and Crowe introduced me to Pearl Jam (lead guitarist McCready, singer-frontman Vedder, bassist Ament and rhythm/lead guitarist Gossard; temporary drummer Dave Krusen was absent and would soon be replaced). They'd already taken Seattle by storm and had done a fair amount of touring, and they were visiting Crowe's set shortly before finishing sessions on "Ten," the debut album (released five months later) that gradually built juggernaut momentum and ensured their future as alt-rock superstars.

It was a too-brief encounter; I've often wished I could time-travel back to that day and give the guys in Pearl Jam a little hint of what was in store for them. I'm sure they were confident about "Ten," but nobody had any way of knowing how big they'd become. Still, it was clear that Vedder, recruited just four months earlier, was a perfect choice as their charismatic frontman. Fresh-faced and ready for anything, Vedder and his bandmates were unstoppable by the time "Singles" was released, including club-scene appearances by grunge rockers Soundgarden and Alice in Chains, in September of '92. (Why the delay? Warner Bros. didn't know how to market "Singles" and nearly shelved the film, but the 1991-92 rise of grunge -- specifically, the phenomenal success of Nirvana and Pearl Jam -- gave the studio a ready-made marketing hook.)

Twenty years later, Crowe's astute combination of obsessive fandom and filmmaking skill makes "Pearl Jam Twenty" an intimate and satisfying tribute. Forget for a moment that Crowe's dynamic, performance-driven film focuses on the two-decade history of grunge's most enduring band; its opening scenes set the stage by capturing early-'90s grunge like lightning in a bottle. Crowe has wrangled up an astonishing array of previously unseen footage from multiple sources. In an early sequence we see back-alley video from young rock fans eager to sneak into clubs, unaware that they would soon be major players on the scene. For those of us who lived in Seattle at the time, these and other images provide a kind of a time-capsule homecoming. The look, the sound, the something's-happening atmosphere of grunge is captured here, like the resonant echoes of a sonic boom.

For the uninformed (and for Pearl Jam fans who never tire hearing their favorite origin story), Crowe sets the stage for Pearl Jam's triumph by paying affectionate tribute to Andrew Wood, whose tragic heroin overdose in March 1990 set the stage for Vedder's recruitment in Pearl Jam. Wood was almost certainly going to be a superstar in Mother Love Bone, the fast-rising band he fronted with bandmates Gossard and Ament, but his death left a void that would be soon filled by Vedder. Searching for a singer and a drummer for the new band they were forming from the ashes of Mother Love Bone, Gossard and Ament sent out a five-song demo tape that made its way to former Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Jack Irons (who would later become another temporary PJ drummer), and Irons passed the demo to his friend Vedder, a part-time singer, San Diego surfer and gas station attendant who felt a special connection to the music.

Vedder wrote and sang lyrics to three of the songs and submitted his audition tape as a mini-opera titled "Momma-Son." The original tape, which Crowe presents to Vedder in "PJ20," is now the Pearl Jam equivalent of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Showing the original cassette to Vedder is one of many magical moments that only Crowe could effectively orchestrate as a trusted friend of the band. ("Oh, look," says Vedder, two decades after submitting the cassette, "my old phone number's still on it!" Crowe suggests calling the number to see if Vedder circa 1991 responds. And if he did? Vedder would advise his younger self, "Be careful, get ready.")

Elsewhere, Crowe maintains that past-to-present perspective to subtle effect, showing Vedder in footage from '91, sitting by a beach fire with an acoustic guitar, quietly acknowledging his role as "the new kid." Crowe then recreates the scene 20 years later so the older, wiser Vedder can reflect on those feelings of initial insecurity. It was natural for Vedder to feel a bit anxious back then (in black-and-white footage of Pearl Jam's second-ever club gig on Dec. 22nd, 1990, the "invisible" Vedder bashfully hides behind his long hair while nailing an early version of "Alive"), but his bandmates knew they'd found their guy: McCready recalls hearing the "Momma-Son" audition cassette and asking "Is this for real? Is this a real guy?" because he, like Ament and Gossard, was so immediately blown away by Vedder's unique and obvious talent. In the annals of rock history, it was a match made in heaven.

Anecdotes and performances are presented with spiritual, not chronological continuity. Crowe structures "PJ20" in non-linear fashion, sequencing interviews and concert footage like tracks on an album, resulting in an oral (and aural) history that liberates Pearl Jam from the restrictions of a year-by-year chronicle. That creative philosophy extends to the "PJ20" soundtrack CD: It's not PJ through time so much as PJ revisiting the emotional landscape of their shared histories. In that respect, "PJ20" feels gently aligned with "Living in the Material World," Martin Scorsese's HBO documentary about "quiet Beatle" George Harrison: Both eschew strict chronology in favor of a more personal kind of portraiture.

"PJ20" places appropriate emphasis on the gravitas of the band and its rarely-cheerful music, but it's also light-hearted, funny, and even suspenseful at times -- the latter, especially, during a montage of the many occasions Vedder might've gotten himself killed by swinging from stage rafters, camera cranes, and scaffolding before wantonly diving into mosh pits and body-surfing on crowds of supportive concert-goers. (As Gossard recalls, "We were terrified every time he did it.") Things lighten up with a silent-film parody relating Pearl Jam's "Drummer Story" (they went through several before, as Gossard states, "Matt Cameron made us a better band than we ever were"), and one of the film's greatest, previously unseen moments occurs when we see "grunge rivals" Vedder and Nirvana's Kurt Cobain, playfully slow-dancing backstage at the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards. (So much for rivalry: Before he died, Cobain reversed his earlier, arguably petty disdain for Pearl Jam.)

Another backstage moment reveals the special kinship that evolved, over the years, between Pearl Jam and Neil Young, "the godfather of grunge." While introducing Young's induction into the Rock 'n Roll Hall of Fame, Vedder mischievously observes that Pearl Jam were seated near the table reserved for executives from Ticketmaster, the company that Pearl Jam triumphantly challenged as a greedy monopoly. As Vedder jokes about the potential for a food fight between tables, we see Young beaming proudly backstage, watching Vedder's introduction on a monitor and laughing along with fellow rebels Willie Nelson, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page. Then and now, it's a moment to savor.

Happy or sad, dark or light, those moments are abundant in "PJ20": McCready in 2001, reaching deep inside to deliver an otherworldly guitar solo on "Reach Down" that would've impressed Jimi Hendrix; Vedder in 1991, surprising his bandmates by turning physically and vocally fierce in response to the harsh removal of a drunken concert-goer by overzealous security thugs; Gossard nonchalantly finding a Grammy award gathering dust in a dark basement storage room; Vedder paying tribute to Cobain during a 1994 Pearl Jam concert on the day Cobain died; and Pearl Jam marking a grave but ultimately meaningful ten-year turning point when nine fans died in a stage-rushing crush during Pearl Jam's performance at the Roskilde, Denmark music festival in 2000. Nobody survives in rock for 20 years without experiencing such euphoric highs and devastating lows.

Crowe also captures the absurdity that ensued when grunge got co-opted by the shallower forces of popular culture: Pearl Jam as a quiz-show answer on "Jeopardy!" and "Wheel of Fortune" and, perhaps inevitably, the ridiculous arrival of grungy, flannel-based clothing designs on the runways of the international fashion scene.

Is it any wonder that grunge's pioneers gradually distanced themselves from the label of "grunge"? It was a vibrant, regional music that was embraced on a global scale, and its moment -- its movement -- came and went like punk before it, but its impact and relevance remain. Pearl Jam suffered through the passage of that moment, but like any great band they changed with the times without changing who they are. If 2000's "Binaural" LP marked a low point when the band was struggling to define its second-decade identity, 2009's "Backspacer" provided all the proof anyone needed that Pearl Jam was entering its third decade as a force to be reckoned with.

As if to acknowledge Pearl Jam's ongoing vitality, Crowe uses "Just Breathe," the lovely hit-single ballad from "Backspacer," to accompany the end credits of "Pearl Jam Twenty." That song might've seemed out of place on previous PJ albums (and who could've predicted that Vedder would release a solo album of "Ukelele Songs" 20 years after joining Pearl Jam?), but now it's a fitting way to end a film about a band that grew and evolved without losing track of its origins.

"Pearl Jam Thirty," anyone? Some sequels are worth waiting for.

_ _ _ _ _

A Seattle-based freelancer, Jeff Shannon has been writing about film and filmmakers since 1985, for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (1985-92) and The Seattle Times (1992-present). He was the assistant editor of Microsoft's "Cinemania" CD-ROM and website (1992-98), where he worked with rogerebert.com editor Jim Emerson, and was an original member of the DVD & Video editorial staff at Amazon.com (1998-2001). Disabled by a spinal cord injury since 1979 (C-5/6 quadriplegia), he occasionally contributes disability-related articles to New Mobility magazine, and is presently serving his second term on the Washington State Governor's Committee on Disability Issues and Employment.